If you were to wander into the rare books section of the Free Library of Philadelphia, you might see an unusual exhibit. In a glass case, rustically framed with tree branches; perched in a miniature landscape of rocks, ferns and soil; is what appears to be a stuffed raven.

Despite being more than 175-years-of-age, the raven’s feathers still gleam, his head is still held in a position of half-amused arrogance, and his eye – though presumably made of glass – still shines mischievously.

It may surprise you to know that this raven was once named Grip and was kept as a pet by none other than Charles Dickens. It may come as a surprise too that this raven’s intelligence and personality were so forceful that the bird not only helped inspire Dickens’s 1841 novel Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of ‘Eighty’, but also one of the most famous poems ever penned – The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe.

Ravens are ominous birds in folklore. Their habit of feasting on carrion, their funereal black plumage, their death rattle of a croak, and their tendency to haunt gibbets and battlefields have linked them with death and slaughter. Yet their playfulness, intelligence and ability to mimic human speech have also seen them associated with prophecy, wisdom and witchcraft.

But how did Grip and his antics inspire Dickens to write one of his darkest novels, a novel in which the shadow of the gallows lies over the book? And what was the strange connection between Charles Dickens, Grip the raven, Edgar Allan Poe and Poe’s best-known poem?

Keep reading for tales of the Devil, black magic, gods of wisdom, sinister letter openers, and the talkative and rascally ravens that harassed Dickens’s children and even managed to dominate his dogs.

The stuffed body of Charles Dickens’s pet Grip the raven, in the Free Library of Philadelphia

Charles Dickens, His Pet Grip the Raven and Grip’s Successors

As a writer with a tendency towards the gothic and macabre, it’s perhaps not surprising that Charles Dickens acquired a raven as a pet. In the preface to Barnaby Rudge, Dickens described how a friend gave him a young raven, who ended up sleeping in Dickens’s stable ‘generally on horseback’. Dickens named the bird ‘Grip’ and was soon impressed by ‘the superiority of his genius.’

Grip – who Dickens’s daughter Mamie characterised as ‘mischievous and impudent’ – may have been banished to the stable because of his habit of biting the ankles of Dickens’s children. Once installed in the carriage house, the bird’s cleverness soon enabled him to dominate an unfortunate Newfoundland dog. Grip would even ‘walk off unmolested with the dog’s dinner right before his face.’

Grip was also keen on attacking the trousers of a local butcher and a carpenter indignantly accused the bird of stealing one of his tools, a clasp knife or hammer. Grip soon became adept at copying various expressions of human speech, boasting ‘an impressive vocabulary.’

Dickens grew increasingly fond of the raven, admiring how he was ‘rising rapidly in acquirements and virtues, when, in an evil hour, his stable was newly painted.’

With his natural curiosity, Grip the raven ‘observed the workmen closely, and saw they were careful of the paint and immediately burned to possess it. On their going to dinner, he ate up all they had left behind, consisting of a pound or two of white lead; and this youthful indiscretion terminated in death.’

Dickens consoled himself by getting two new birds, an eagle and another raven, who he also named Grip. The second Grip was ‘an older and more gifted raven’, who a friend of the writer had discovered at a Yorkshire village pub. The first task of this bird, Dickens wrote, was to dig up ‘all the cheese and halfpence’ that the first Grip had buried in the garden, ‘a work of immense labour and research, to which he devoted all the energies of his mind.’

Like the first Grip, this bird was talented at repeating various phrases, and he also had an accomplishment for imitating different sounds. Dickens wrote that he would ‘perch outside my window and drive imaginary horses with great skill all day’. Grip could also replicate the noise made by corks popping out of champagne bottles. The author once met the second Grip ‘about half-a-mile from my house, walking down a public street, attended by a pretty large crowd, and spontaneously exhibiting the whole of his accomplishments.’

This raven also amused itself by digging out mortar from the garden walls and by breaking windows by chipping away at the putty holding the glass in the frames. In addition, Grip ‘tore up and swallowed in splinters, the greater part of a wooden staircase.’

Dickens feared this raven was ‘too bright a genius to live long’ and, after Dickens had owned Grip for about three years, he died ‘before the kitchen fire’, turning ‘over on his back with a sepulchral cry of “cuckoo!”’

In the preface to Barnaby Rudge, Dickens complained, ‘I have since then been ravenless’, but he would go on to get a third such bird, who he’d also call Grip.

This third raven had an even more forceful character than his two predecessors. He also dominated the family dog, now a large bullmastiff. The Bullmastiff would sit patiently while Grip helped himself to the best slices of meat from the dog’s bowl.

So How Did Grip the Raven End up Stuffed?

When the first Grip died, Charles Dickens seems to have been genuinely upset. He wrote a letter to his friend, the illustrator Daniel Maclise, in which his grief is mixed with a certain dark humour.

In the letter, Dickens stated that when Grip became ill, the vet ‘administered a powerful dose of castor oil.’ This restored the bird to the extent that he bit the coachman and Grip was able eat ‘some warm gruel’ the next day.

Grip, alas, soon suffered a relapse: ‘On the clock striking 12 he appeared slightly agitated, but soon recovered, walking twice or thrice along the coach-house, stopped to bark, staggered, exclaimed “Halloa old girl” (his favourite expression) and died. He behaved throughout with a decent fortitude, equanimity, and self-possession, which cannot be too much admired … The children seem rather glad of it. He bit their ankles. But that was play.’

Dickens sent his letter in an envelope that bore a huge black seal. Upon reading it, Maclise was saddened – or amused – enough to decorate the letter with a sketch of Grip’s spirit ascending to heaven.

The letter Dickens sent to Daniel Maclise on the death of Grip the raven, and the sketch Maclise added to it

Dickens also paid tribute to the bird by asking a taxidermist to stuff and mount it. He then placed the glass case containing Grip over his desk so his beloved raven could look down on him as he wrote. The raven seems to have been a fruitful – if somewhat morbid – muse. Dickens would produce 16 novels – as well as short stories and numerous articles – under Grip’s dark gaze.

The second Grip avoided such a destiny, being laid to rest beneath a tree in Dickens’s garden. But Dickens did have a habit of creating macabre memorials to his pets. Dickens’s cat Bob, according to Mamie, ‘was always with him, and used to follow him about the garden like a dog, and sit with him while he wrote.’ Bob, who was ‘profoundly deaf’, liked to snuff out Dickens’s candle as he was reading – in the hope the writer would then pay attention to him instead of his books.

When Bob died, Dickens had one of his paws stuffed and attached to the ivory blade of a letter opener. The blade is inscribed ‘C.D. In Memory of Bob 1862’. It’s thought Dickens had Bob’s paw converted into the letter opener’s handle so he could still enjoy fondling the soft fur of his adored cat.

How Charles Dickens’s Pet Ravens Inspired Barnaby Rudge

Barnaby Rudge is set during the Gordon Riots of 1780, England’s worst ever civil disturbances. Though ostensibly a Protestant reaction against plans by the British Establishment to remove some of the legal disadvantages and restrictions facing Catholics, the riots are now seen more as an explosion of the pent-up frustration and rage of London’s poor and underclass. In Barnaby Rudge, the rioters converge on Parliament, roughing up MPs and members of the House of Lords. They plunder and pull down Catholic churches, storm and set fire to London’s jails, and attack, loot and burn the houses of Catholic citizens.

The book’s main character Barnaby – a good-natured simpleton who gets caught up in the disturbances – is accompanied almost everywhere by his pet raven, Grip.

The raven’s darkly amusing antics add a tone of black comedy to a book filled with fire, murder, destruction, and the threat of the gibbet that looms over the rioters. Grip hovers over and struts through the novel like a burlesque herald of doom, a carnivalesque spirit predicting death and calamity. In folklore, the raven is associated with death, carnage, prophecy, the Devil and witchcraft, and Dickens drew on such ideas when sculpting the character of Grip.

A scene from Charles Dickens’s Barnaby Rudge, showing Grip the raven

In one particularly gothic passage, Grip hops through a graveyard, in which ‘sometimes, after a long inspection of an epitaph, he would strop his beak upon the grave to which it referred and cry in his hoarse tones “I’m a devil! I’m a devil!”’

Another scene has Grip strutting around some characters ‘round and round, as if enclosing them in a magic circle, invoking all the powers of mischief.’

In the preface to Barnaby Rudge, Charles Dickens stated, ‘The raven in this story is a compound of two great originals, of whom I was, at different times, the proud possessor.’ These originals, of course, were Dickens’s first two pet ravens.

In a letter to his friend George Cattermole, dated 28th January 1841, Dickens wrote, ‘My notion is to have Barnaby always in company with a pet raven, who is immeasurably more knowing than himself. To this end I have been studying my bird, and think I could make a very queer character of him.’

The influence of Dickens’s two Grips can clearly be seen in Barnaby Rudge. There’s the fictional raven’s loquaciousness, his repertoire of phrases and his fondness for imitating various sounds, including the popping of champagne corks.

‘A devil! A devil! A devil!’ Grip cries. ‘Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah! Keep up your spirits! Never say die! Bow, wow, wow!’

‘Grip! Grip! Grip!’ the bird croaks on another occasion. ‘Grip the clever! Grip the wicked! Grip the knowing! Grip! Grip! Grip! Grip! I’m a devil! I’m a devil! I’m a devil! Never say die! Hurrah! Bow wow wow! Polly put the kettle on, we’ll all have tea!’

Following this particular outburst, Grip – for the entertainment of an onlooking gentleman – ‘drew fifty corks at least and then began to dance.’ The raven is also capable of barking ‘like a lusty housedog.’

Later Grip even incorporates the Protestant obsessions and anti-Catholic slogans of the rioters into his vocabulary: ‘I’m a devil, I’m a polly, I’m a kettle, I’m a Protestant, No popery … Never say die, bow wow wow, keep up your spirits, Grip, Grip, Grip, Holloa! We’ll all have tea! I’m a Protestant kettle, no popery!’

Other antics of Dickens’s pets can be found in the character of Grip. The raven spends portions of the book banished to stables and like Dickens’s raven, Grip can draw a crowd: ‘His conversational powers and surprising performances’ had ‘rendered him famous for miles around … and many persons came to see the wonderful raven.’

Dickens also has Grip ‘biting the ankles of vagabond boys (an exercise in which he much delighted) … and swallowing the dinners of various neighbouring dogs, of whom the boldest held him in great awe and dread.’

There can be little doubt, then, that Dickens’s mischievous and talkative pet ravens helped inspire his Grip character. Though Barnaby Rudge wasn’t one of Charles Dickens’s most successful novels, it was serialised in his magazine Master Humphrey’s Clock and – as we shall see below – some of Grip’s catchphrases entered popular culture. And Grip would go on to inspire an even more famous literary work.

Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven

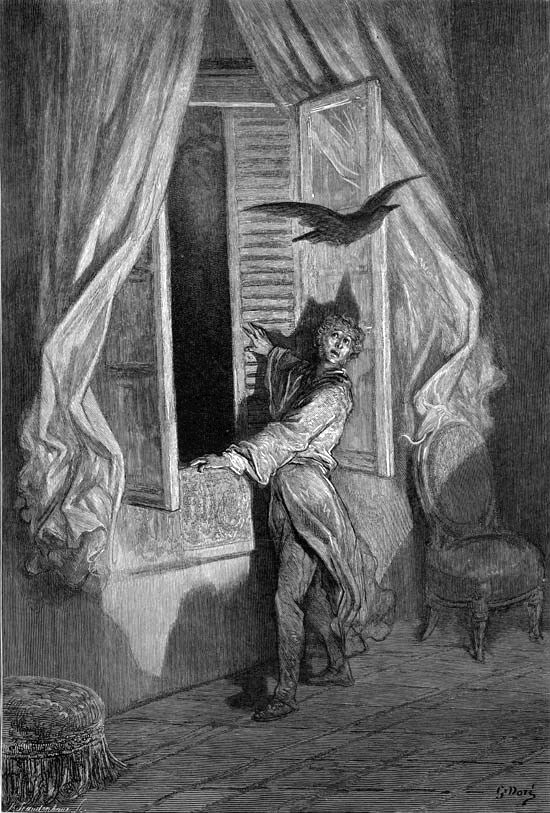

Dickens wasn’t the only Victorian writer who utilised the raven’s literary power. In January 1845, Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven was published. This dark poem has a young student, who is grieving for a dead lover (‘The lost Lenore’), being disturbed late at night by ‘a tapping, as of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.’ Realising the sound is coming from the window, the student opens the shutters and is surprised to see a raven step haughtily into his room. The poem is in the video below – read by the English horror actor Christopher Lee – if you’d like to hear it.

The poem draws on many of the sinister associations ravens have in myth and folklore. There are nods to black magic. The raven taps at the window ‘upon a midnight dreary’ (the witching hour) ‘in the bleak December’ (the darkest month and therefore the one most closely linked to evil) as the student is reading ‘many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore’ (black magic books?). The narrator also calls the raven ‘a devil’.

The Raven is mainly written in trochaic octameter, a rhythmic pattern in which one stressed syllable is followed by an unstressed one, repeated eight times per line. This gives the poem a hypnotic, bewitching quality. Trochaic metre is quite unusual in English verse and is more often used in songs, chants and magic spells. Poe adds to this darkly captivating effect with alliteration: ‘grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt and ominous bird of yore’.

Poe also stresses the raven’s mythological links to death. The student asks the bird ‘what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore?’ Pluto is the god of the Roman underworld and king of the dead. The narrator frequently asks the raven about the possibility of meeting his lost Lenore in some sort of afterlife. The raven has just one answer, the only word he speaks in the poem: ‘Nevermore’. The bird’s continual repetition of ‘nevermore’ mocks the student’s attempts to establish whether there is any hereafter, any meaning to existence or point to his sufferings. The ‘nevermore’ serves as a cynical refrain to the verses filled with the student’s agonised questions and ramblings.

An illustration by Paul Gustave Dore for Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven

We might ask why the student sees the bird as some sort of oracle. Folklore and myth link ravens – probably due to their ability to speak and high intelligence – to prophecy, wisdom and cunning. When the raven comes into the student’s room, he perches ‘upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door’. Pallas Athena is the Greek goddess of wisdom. An old Irish proverb states ‘there is wisdom in a raven’s head’, in the Hebrides children would be encouraged to drink from a raven’s skull to gain the gifts of prophecy and wisdom, and the Native American Kwakiutl people exposed their sons’ placentas to ravens in the hope this would give them second sight. Such notions can be seen in Poe’s poem: ‘Prophet! Thing of evil! – Prophet still, if bird or devil!’

The Raven was soon published in magazines across the United States and had an immediate impact. The editor of the Evening Mirror praised it as ‘unsurpassed in English poetry for subtle conception, masterly ingenuity of versification, and consistent sustaining of imaginative lift … It will stick to the memory of everybody who reads it.’

The poet Elizabeth Barret wrote to Poe: ‘Your Raven has produced a sensation, a fit o’ horror, here in England. Some of my friends are taken by the fear of it and some by the music. I hear of persons haunted by “Nevermore”.’ The New World declared, ‘Everyone reads the Poem and praises it … justly, we think, for it seems to us full of originality and power.’

The raven – an intelligent and playful bird – is linked with prophecy, death and witchcraft in folklore. (Photo: Visit Heritage)

Not everybody was impressed. William Butler Yeats felt the poem was ‘insincere and vulgar … its execution a rhythmical trick’ while Ralph Waldo Emerson stated dismissively, ‘I see nothing in it.’ Parodies were published: The Craven, The Gazelle, The Whipporrwill, The Turkey and The Polecat. But, if anything, this ridicule added to Poe’s fame and that of his sinister poem.

Poe himself came to be nicknamed ‘The Raven’. He received many invitations to lecture and to recite his celebrated poem, both publicly and at private events. A guest at one such gathering wrote Poe would ‘turn down the lamps till the room was almost dark, then standing in the centre of the apartment he would recite … in the most melodious of voices … So marvellous was his power as a reader that the auditors would be afraid to draw breath lest the enchanted spell be broken.’

But What’s the Connection between Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Dickens, Barnaby Rudge and Grip the Raven?

Though Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven is widely known, many people don’t realise that at least some of its inspiration came from Dickens’s work. Poe reviewed the first four serialised chapters of Barnaby Rudge for Graham’s Magazine. He predicted how the novel would end and when – on reviewing the complete book – Poe found his ideas were somewhat askew, he blamed Dickens’s plotting skills rather than his own foresight.

Poe was, however, mostly positive about Barnaby Rudge and especially fond of the character of Grip. He described the raven as ‘intensely amusing’ though he was disappointed by the fact Grip was only a minor character.

Poe argued that Grip’s ‘croaking might have been prophetically heard in the course of the drama. Its character might have performed, in regard to that of the idiot, much the same part as does, in music, the accompaniment in respect to the air.’

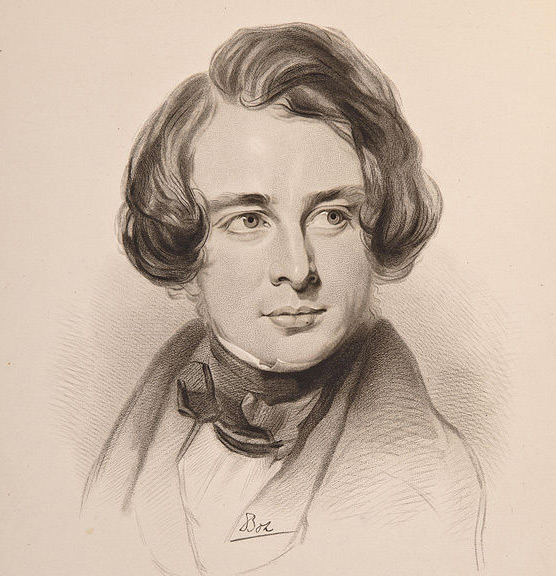

When Poe found out Dickens was planning a reading and promotional tour of the States, he sent the novelist a letter – along with a book of his short stories – and the two men corresponded. Dickens set out for America accompanied by his wife Catherine and also by a portrait – by Daniel Maclise – of the Dickens children and Grip. Meeting Dickens – in March 1842, in a Philadelphia hotel – Poe saw the portrait and was intrigued. Poe was even more amazed to discover that the raven in the painting had not only been Dickens’s pet, but had served as a model for the fictional Grip.

The portrait of Charles Dickens’s children with Grip the raven, who inspired Edgar Allan Poe

During their meeting, Poe attempted to impress Dickens with his abilities as a poet, storyteller and critic in the hope that Dickens might use his contacts in England to help Poe establish his literary reputation there. It did seem that Dickens was taken with Poe and he said he’d try to find the American author an English publisher.

But to what extent did Barnaby Rudge influence The Raven? There’s a scene in Dickens’s novel where the character Gabriel Varden overhears Grip and says, ‘What was that? Him tapping at the door? Tis someone knocking softly at the shutter. Who can it be?’

Poe depicts his raven as having an aristocratic arrogance: ‘with mien of lord or lady perched above my chamber door’. Dickens gives Grip a similar attitude, having him strutting ‘not in a hop, or walk, or run, but in a pace like that of a very particular gentleman with exceedingly tight boots on, trying to walk fast over loose pebbles.’

A sketch of a young, energetic Charles Dickens in 1842 – the year he met Edgar Allan Poe on his first American reading tour.

Though Poe drew from folklore and myth to create his poetic raven, he cannot have failed to have noticed the references in Barnaby Rudge to the bird’s devilish intelligence and cunning. Characters refer to Grip as a ‘knowing imp’, ‘a dreadful fellow’ and ‘a devil’, with one saying ‘the Devil’s loose in London somewhere.’

Poe’s raven’s refrain of ‘Nevermore’ – with its spookily long vowel sound – may also have been inspired by Barnaby Rudge. When Grip is put in prison with Barnaby towards the novel’s end, he loses his loquaciousness and repeatedly croaks the mournful word, ‘Nobody’.

The similarities between Poe’s and Dickens’s literary ravens didn’t escape the critics of the time. In 1848, the poet James Russell Lowell wrote, ‘There comes Poe with his raven, like Barnaby Rudge, Three-fifths of him genius, and two-fifths sheer fudge.’

Poe and Dickens’s friendly relationship wouldn’t last. Poe was disappointed by Dickens’s failure to find him a publisher in England. He also seems to have believed – probably wrongly – that Dickens was the author of a review dismissing Poe as an imitator of Tennyson. Plagiarism was a sensitive subject for Poe – he accused Henry Wadsworth Longfellow of this crime while Poe himself was accused of plagiarising The Raven from an anonymous poem called The Bird of the Dream. The correspondence between Poe and Dickens ceased though Poe remained largely supportive of Dickens’s writing.

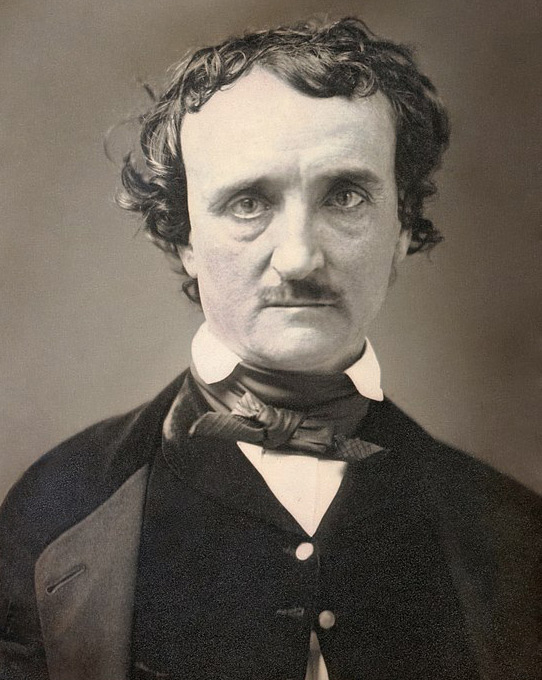

Edgar Allan Poe in 1849

Despite the fame The Raven brought Poe, he made little money from it, having sold the rights to The American Review for $9. The poet bitterly remarked, ‘I am as poor now as I ever was in my life – except in hope, which is by no means bankable.’ Poe died in poverty on October 7th, 1849. His wife was already dead, but his mother-in-law – to whom Poe had been close – was left destitute. In 1868, during Dickens’s second visit to America, he looked Poe’s mother-in-law up and ‘generously entreated her acceptance of $150 with the assurance of his sympathy.’

Just as Grip the raven linked the life and work of Edgar Allen Poe and Charles Dickens, he would link them in death. In April 1869, Dickens – exhausted by his extensive and theatrical reading tours; worn out by workaholism and health problems – suffered a stroke. He didn’t, however, give up his punishing writing regime. He pressed on with his 20th novel – The Mystery of Edwin Drood – labouring in his study, as always, under Grip’s gaze. It was there, beneath the raven’s eye, on 8th June 1870, that he had another stroke following a full day’s work. Dickens never recovered consciousness and died the next day. He was 58.

A much older and more haggard-looking Charles Dickens on his second American reading tour

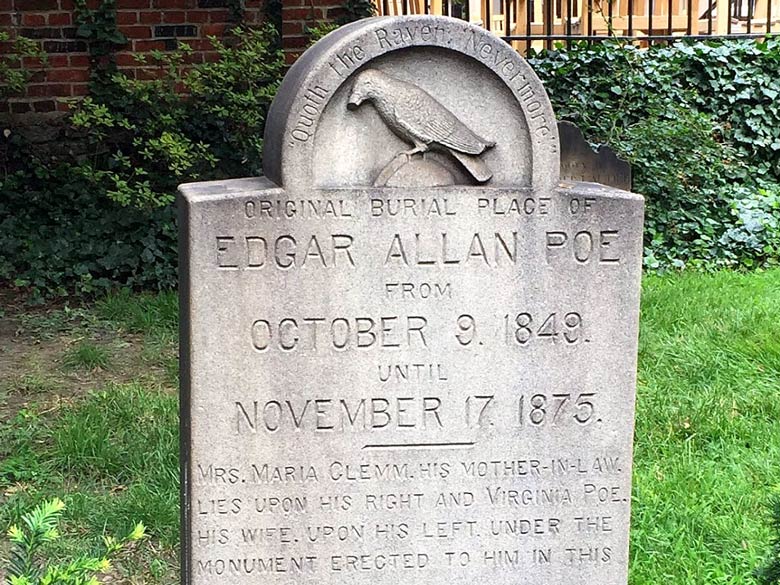

Poe died in mysterious circumstances in Baltimore at the age of just 40 and was buried in the same city. A simple, numbered sandstone block at first marked his grave – a train had destroyed his intended tombstone by smashing through a mason’s yard. In the early 1870s, people began to complain about the state of Poe’s grave and money was raised for a more dignified memorial. An impressive monument was built and Poe’s remains were exhumed and placed beneath it, later being joined by those of his mother-in-law and wife. This memorial features – perhaps surprisingly – no homage to the raven that brought Poe such fame. In 1913, however, a commemorative stone was set up to mark the plot where Poe lay before his reburial. A raven is carved on the stone’s top with ‘Quoth the Raven Nevermore’ inscribed around it. Thus, not only Poe is honoured, but so is the lively and devious raven from across the Atlantic that inspired two of the Victorian era’s darkest and most influential writers.

The stone marking the original burial place of Edgar Allan Poe – inscribed with a famous line from The Raven. (Photo: Wanderlust on a Budget)

But what of Grip himself? How did the stuffed body of this very English bird end up in – of all places – Philadelphia? Via his mischievous and eventful life, Grip forged connections between the literature of America and Britain. It’s maybe, then, fitting that in death the raven would embark on a strange continent-hopping odyssey.

Grip the Raven’s Strange and Gothic Afterlife

Following Charles Dickens’s death, a number of his possessions – Grip included – were auctioned at Christie’s, London. The audience was made up of collectors, speculators, Dickens fans, and a group of fashionable personages who’d levered themselves away from the Eton versus Harrow cricket game taking place at Lord’s.

As the auction progressed, the crowd became more excitable and when Grip was brought out, he was greeted with yells of ‘I’m a devil! I’m a devil!’ and other catchphrases from Barnaby Rudge.

Just as the hammer was about to fall at 62 guineas, there was a shout of ‘Never say die!’ and the price almost doubled to 120. Grip ended up being sold to a George Swan Nottage.

Born to a Cripplegate butcher, Nottage would eventually go on to become London Lord Mayor. Nottage ran a stereoscopic photo company and it’s thought he bought Grip so he could produce stereoscopic images of the well-known bird. When Nottage died in 1885, Grip was inherited by his widow. After she died, Grip became the prize attraction in the auction of her possessions, held in 1916. His value had, however, fallen – The Times reported Grip sold for just 78 guineas.

Grip was bought by Walter Thomas Spencer, the proprietor of a second-hand bookshop on New Oxford Street. Here, according to the writer Thomas Malt, amongst the shop’s ‘dusty, cosy quietude’ Grip remained half-hidden in ‘the tarnished shadows of a London winter.’ The raven’s next owner was the wealthy collector Ralph Tennyson Jupp, a pioneer of the film industry, who wanted to set up a Dickens museum.

In 1921, however, Jupp died after being kicked by a horse. Jupp’s impressive collection of Dickens artefacts – which included the author’s eyeglasses and penknives – was sold at the Anderson Galleries in New York. Grip – lauded by the catalogue as ‘probably the most famous bird in the world’ – went for $310.

Grip ended up back in London, where he was displayed in the window of a bookshop belonging to Charles John Sawyer, also in New Oxford Street. The raven was later purchased by one Charles Sessler, who kept him in his bookshop in Walnut Street, Philadelphia. Grip was then acquired by Colonel Richard Gimbel, a collector of rare books and manuscripts who had a passion for the work of Edgar Allan Poe. When he died, Gimbel left his collection to the Free Library of Philadelphia.

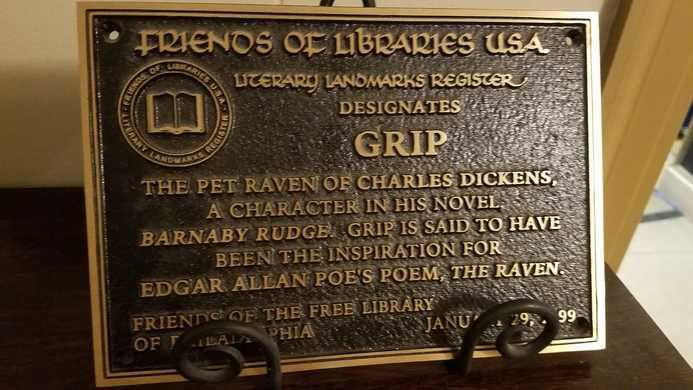

Grip’s plaque in the Free Library of Philadelphia – acknowledging his influence on Poe’s The Raven and Dickens’s Barnaby Rudge (Photo: Atlas Obscura)

Grip still perches there today. Perhaps the raven feels at home, as the library houses plenty of Dickens memorabilia, including dozens of the author’s letters, first editions of his books, and original artworks for his novels. The library also contains the desk at which Dickens worked on his final novel, the very desk Grip looked down on as his master strove – and failed – to complete his last book.

(This article’s main image shows Grip the raven in the Free Library of Philadelphia)

Reading this was like a journey into time, brought so much meaning to stories I read as a child at a public library in Zimbabwe. Thank you so much for sharing. This is indeed an intriguing blog and is inspiring me to take up writing all over again.

Thank you, Evans, ravens are the most inspiring creatures – as Poe and Dickens both prove.