In the Summer of 1816, a group of young Britons were gathered in a villa on the shore of Lake Geneva, Switzerland. But this was no ordinary summer – black clouds clogged the sky, thunder shuddered the lake’s surface, rain streaked down, lightning forked and flashed around the mountains, and clammy cold grasped the young people’s limbs. In that miserable, apocalyptic summer, harvests had failed across Europe and – according to Lord Byron, one of those at the villa – Geneva had even endured ‘a celebrated dark day when the fowls went to roost at noon, and candles were lighted as at midnight’.

The house’s name was the Villa Diodati and those sheltering in it were no ordinary young people. As well as Lord Byron – the most successful, charismatic and infamous poet of the age – there was the equally talented poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, his soon-to-be-wife Mary and her stepsister Claire Clairmont. As thunder rumbled and lightning crackled outside, the atmosphere within the Villa Diodati was also somewhat charged. Shelley had recently abandoned his wife to elope with Mary, but – just to intensify the sexual and romantic complications – Claire may have been Shelley’s mistress. Claire was also Byron’s paramour and – though Byron had been reluctant to take on Claire as a lover – she was now pregnant with his child.

There was another figure at that gathering. I imagine him – a black-haired, moodily handsome man – sitting sulkily in a corner as the dark room flashed with lightning and flickered with feeble candlelight. That young man was John William Polidori. Though officially employed as the personal doctor of the hypochondriac Lord Byron, Polidori harboured literary ambitions of his own. Arrogant and oversensitive, tortured – even in that forward-thinking group – by the difference in class between himself and his aristocratic companions, Polidori smarted and fumed at every perceived slight or put-down.

Polidori – though his relationship was Byron was fraught and complex – did view his employer as a model of literary achievement he could emulate. Polidori’s literary yearnings would – in a strange way – be fulfilled, but hardly in the manner he would have hoped for. There was also – to add to the passionate tensions in the Villa Diodati – the fact that John William Polidori was probably bi- or homosexual and very likely in love with his famous, though much resented, boss.

John William Polidori, the author of the first vampire novel

Mixed into all this volatile alchemy were the heady effects of the pipes of opium being passed around, the vials of laudanum on the tables, and the carafes of red wine that glinted in the candlelight. Looking back, it seems inevitable that something of significance – something horrifying, even, something that would shake generations of readers – would come out of that combination of that claustrophobic cooping-up of genius, that narcotically-fuelled swirl of envy and sexual longing, and those dark symphonies of nature thundering outside.

The cold and storms of 1816 – known as ‘the year without a summer’ – were due to the eruption of an Indonesian volcano called Mount Tambora. The volcano had spewed masses of sulphurous fog into the atmosphere, fog which went on to encircle the earth, dimming sunlight, perverting weather patterns and causing frost and ice well into summer. These gloomy conditions inspired Lord Byron’s excellent poem Darkness:

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguish’d and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless and pathless and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air …

The summer at the Villa Diodati also resulted in the birth of the two most important – and unsettling – modern gothic archetypes: Frankenstein’s Monster and the aristocratic literary vampire. This latter character would go on to inspire Dracula author Bram Stoker, among others.

Both Frankenstein’s Monster and the vampire manifested out of what would be innocent attempts to pass the time as black clouds shrouded the sun, as lightning sparked, and as John William Polidori struggled with jealousy, bitterness and rage.

Was Lord Byron the model for the literary vampire?

The Modern Vampire Arises out of a Ghost Story Contest at the Villa Diodati

To lessen the boredom of their confinement, the group took to reading out spooky stories in the evenings, such as those from the Fantasmagoriana, a French collection of translated German horror tales. Near midnight, on 18th June, Byron was reading from Christabel, a gothic poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. As Byron recited the poem in a hypnotic voice, Shelley leapt up and ran shrieking from the room. He’d later say he’d seen a terrifying vision of Mary – who’d been in the corner nursing their child – with staring eyes instead of nipples on her breasts.

Byron soon suggested that each person in the Villa Diodati should write a ghost story of their own. I imagine the little group, heads bent, faces frowning in concentration as rain pounded the roof, as wind moaned and thunder quaked around the Villa’s walls. It would not, however, be the two great poets who’d be responsible for unleashing the most enduring visions on the world. Shelley produced little while Lord Byron only managed to write what would later be called The Burial: A Fragment (or Fragment of a Novel), a few pages of an unfinished story about an English aristocrat getting sucked into vampiric goings-on in Turkey.

Percy Bysshe Shelley was also at the Villa Diodati, though he didn’t manage to write much of a ghost story.

Polidori’s initial effort provoked ridicule. He conjured up a tale about a peeping tom, who was horrified to realise the woman he was gawping at had a bare skull for a head. Mary Shelley later commented, ‘Poor Polidori had some terrible idea about a skull-headed lady who was so punished for peeping through a keyhole, what to see I forget.’

Mary would soon jerk bolt upright in her bed, waking screaming from a nightmare – or vision – in which, she asserted, ‘I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together; I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out.’ The idea for Frankenstein had been sparked into life.

Polidori – though the proud doctor snarled and bristled against the laughter and mockery his story generated – would, when he calmed down, re-examine the Fragment Byron had penned.

Polidori would take Byron’s casually tossed-off, unfinished vampire tale and work it over. Unknown to Byron, Polidori began escaping the Villa Diodati’s brooding atmosphere by rowing across the lake to light-hearted social gatherings organised by one Countess Breuss. Here John met a Madame Brelaz, who was soon captivated by his charms. With their encouragement, he would create a literary archetype that has flourished right up to the present day. The story Polidori produced would become a novella entitled The Vampyre.

The Villa Diodati, where both Frankenstein and the aristocratic literary vampire were born

Lord Byron and John William Polidori between Them Invent the Aristocratic Literary Vampire

Our modern image of the vampire is usually of a being who – while indulging in brutal acts to sate his need for blood – is suave, educated, sexually compelling and from the aristocratic layer of society.

This darkly charismatic figure seems puzzling when you consider how vampires were originally depicted in the folklore of Central and Eastern European, the Balkans and Turkey. The vampires of peasant legend were hideous shuffling corpses more akin to zombies than to the charmingly evil, well-travelled and sophisticated bloodsuckers of later literature and film.

Claire Clairmont, lover of Lord Byron and guest at the Villa Diodati

The folkloric vampire could not rest, thanks to the fact it had died by suicide or been murdered or improperly buried. At night, these stinking cadavers would totter from their tombs, searching for relatives and ex-neighbours in order to suck their blood and so prolong their miserably undead existence. A simple and parochial figure, the vampire couldn’t travel far from its native soil and rarely harassed anyone outside its former village. When the vampire’s neighbours realised what was going on, they would end the nosferatu’s wanderings by hammering a stake through its heart – pinning the creature to the earth, thereby encouraging decomposition to proceed more naturally.

Byron had heard about such legends on his journeys through Turkey and South East Europe, both heartlands of the traditional vampire myth. A vampire of this type crops up in Byron’s poem The Giaour (1813), set in the Ottoman Empire:

But first, on earth as vampire sent,

Thy corse shall from its tomb be rent:

Then ghastly haunt thy native place,

And suck the blood of all thy race;

There from thy daughter, sister, wife,

At midnight drain the stream of life;

Yet loathe the banquet which perforce,

Must feed thy living livid corse.

This vampire is still the creature of rural legend – an animated carcass that stumbles around its former environs, desperate to feed on its relatives’ blood. In the Fragment of a Novel, however, Byron introduced a radically different vampiric archetype – a character that would be further elaborated in Polidori’s The Vampyre.

Mary Shelley in 1840. Her experiences in the Villa Diodati helped inspire Frankenstein.

Lord Byron’s The Burial: A Fragment

The vampire in A Fragment is one Augustus Darvell. Educated in aristocratic British schools, Darvell is well-travelled and ‘a man of considerable fortune and ancient family’. Though moody and enigmatic, he appears human and socialises with London’s elite. Nothing about him suggests the stench or decay of a corpse.

The narrator is an ex-schoolmate of Darvell’s, who – fascinated by his strange manner – succeeds in befriending him. The two visit Turkey, where – with a local guide – they make an excursion to the ruins of Ephesus. But, on the way, Darvell – who for some time has been growing ‘daily more enfeebled’ – suddenly becomes much weaker. To allow him to rest, the group pause in a Turkish graveyard.

Reclining against a tombstone in the shadow of a cypress tree, Darvell tells his friend he is dying and makes an odd request. He asks his friend to take an elaborate ring from his finger and hurl it into some salt springs ‘on the ninth day of the month at noon precisely’. On the following day, Darvell says, his friend should go to a ruined Temple of Sirius and wait one hour, though he doesn’t reveal what for. Darvell also makes his friend and the guide swear an oath that for one year they will ‘conceal my death from every human being’.

In the cemetery, the narrator notices a stork ‘with a serpent writhing in its beak’ that it – mysteriously – makes no attempt to devour. Darvell tells his companions to dig his grave exactly where the stork is standing. As the bird flies away, Darvell slumps against his friend and dies. The friend watches in horror as Darvell’s ‘countenance in a few minutes became nearly black’. Darvell’s body then starts to decompose at an unnatural speed and the narrator and guide bury him.

Though his companions in the Villa Diodati urged him to go on with his tale, Byron refused. He seemed to have a distaste for writing about vampires, stating in a letter of 1819, ‘I have a personal dislike to “vampires”, and the little acquaintance I have with them would by no means induce me to reveal their secrets.’

Lord Byron in 1813 – was much of our modern archetype of the vampire based on him?

Byron did, however, let slip to Polidori how his story would have continued. Darvell would have risen from the dead – and sustained himself by feeding on the blood of the upper classes. Darvell would have also tried to seduce the narrator’s sister.

And Then John William Polidori Was Inspired to Write The Vampyre

Intrigued by Lord Byron’s story – and by the plot arc the poet had planned – Polidori got to work. He’d later claim he wrote his novella The Vampyre in just ‘two or three idle mornings’.

In The Vampyre, Aubrey – a naïve young gentleman – befriends Lord Ruthven, a mysterious and charismatic aristocrat who has entered London society. The two set off on a grand tour of Europe, but Aubrey – though originally enthralled by Ruthven – becomes disgusted by his behaviour, especially his habit of seducing then discarding women. Aubrey leaves Ruthven in Rome and travels alone to Greece, where he falls for Ianthe, an innkeeper’s daughter. Ianthe shows Aubrey around and schools him in the local vampire lore, but his ‘fair conductress’ is soon discovered murdered:

‘Upon her neck and breast were blood and upon her throat were marks of teeth having opened the vein:- to this the men pointed, crying, simultaneously, struck with horror, “A Vampyre! A Vampyre!”’

This ‘vampyre’ turns out to be Ruthven. Aubrey, however, unaware of this fact, re-joins Ruthven and they travel through Greece. The pair are attacked by robbers and Ruthven is mortally wounded. He makes Aubrey swear not to tell anyone of his death for a year and a day. Ruthven also demands that his body be carried to ‘the pinnacle of a neighbouring mount’ where ‘it should be exposed to the first cold ray of the moon that rose after his death.’

Arriving back in London, Aubrey is amazed to meet Lord Ruthven, apparently alive and in good health. Ruthven insists that Aubrey keeps his oath and Aubrey – traumatised by his experiences abroad and startled by Ruthven’s reappearance – has a nervous breakdown.

Ruthven seduces Aubrey’s sister and it is announced they will marry soon. Aubrey – who has now realised Ruthven’s true nature – tries to alert his family, but his warnings are dismissed as the rantings of a madman. On her wedding night, Aubrey’s sister is found dead, having – according to the book’s last line – ‘glutted the thirst of a VAMPYRE!’ Aubrey also dies – of a broken blood vessel brought on by all the anguish.

Byron and Polidori’s tales have obvious similarities – the fascinating aristocratic vampire, the Continental travel, the naïve friend who tags along, the seduced sister, the strange death that is not a death and the weird rituals the vampire insists should be followed (presumably to ensure his ‘resurrection’).

But an examination of the lives of Byron and Polidori suggests that both their stories have more than a ring of reality about them. The genesis of the aristocratic vampire can be found in the bizarre histories of these two men and in the tormented relationship they shared.

The Strange and Tragic Life of John William Polidori

John William Polidori was born in London in 1795. His father, Gaetano, was an Italian political refugee, his mother an English governess. Polidori’s sister Frances would marry the exiled Italian scholar Gabriele Rossetti, making John the uncle of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his poet sister Christina.

John attended the Catholic school Ampleforth College in Yorkshire, then a remote, draughty, ramshackle establishment very different to the posh boarding school it would later become. From there, Polidori went on to study medicine in Edinburgh. Much of what he learnt – appropriately for one who would write about vampires – focused on purging the body, especially by using leeches to drain the blood. Polidori – also rather vampirically (think Lucy Westerna in Dracula) – wrote his thesis on sleepwalking. He became the youngest ever person to obtain a medical degree, graduating in 1815 at just 19 years of age.

Polidori, however, disliked studying medicine. A moody loner, he described his classmates as ‘automatons’. His passion was, instead, for literature. Like many young men, he longed to follow Byron’s example, perhaps imagining a literary career that would gift him riches, fame and sexual success. In The Vampyre, Polidori reflects with bitterness on his youthful yearnings, describing Aubrey as having ‘cultivated more his imagination than his judgement … he thought, in fine, that the dreams of poets were the realities of life.’

In early 1816, however, Polidori must have felt the most incredible blessing had descended, a piece of luck that brought him closer to his treasured literary aspirations. He was offered the job of personal physician to Lord Byron. Polidori’s father – who’d once been the secretary of the flamboyant dramatist and author Vittorio Alfieri and understood the dangers of working for a vain and famous man – urged his son not to accept the post. But John was unable to resist the magnetic draw of Byron’s talent and charisma. And, anyway, because of his youth, Polidori was forbidden to work as a public doctor. (In London, one couldn’t practise medicine until the age of 26.) Those close to Polidori weren’t the only ones to sense foreboding over the appointment. Byron’s faithful friend John Cam Hobhouse warned the poet not to employ the arrogant, volatile young man.

Byron – due to his good looks, dangerous charms and undeniable literary gifts – had proved a popular figure on London’s social scene, an accomplishment emphasised in both Polidori’s and Byron’s work. In The Vampyre, Ruthven’s ‘peculiarities caused him to be invited to every house, all wished to see him and … were pleased at having something in their presence capable of engaging their attention … many of the female hunters after notoriety attempted to win his attentions …’ In the Fragment, Darvell is an object ‘of attention, of interest and even of regard … a being of no common order, and one who, whatever pains he may take to avoid remark, would still be remarkable.’

But just before Polidori entered Byron’s employment, society’s attitude towards the poet changed from admiration to outraged disgust. Thanks to the dramatic collapse of Byron’s marriage to Annabella Milbanke, lurid rumours were swirling through London and the rest of the country: that Byron had been having an incestuous affair with his half-sister, that he’d sodomised his wife, that he’d been enmeshed in sordid liaisons with numerous actresses and prostitutes. He was even accused – Byron today would be thought of as bisexual – of corrupting his page boy.

To escape all this scandal, as well as the increasing debts his spendthrift nature had racked up, Byron fled London for the Continent on St George’s Day (23rd April) 1816, taking Polidori with him. The pair exited Byron’s home with difficulty. A hostile crowd had gathered around it – a mob Byron feared might lynch him.

At first, the two men got on, but Byron soon became irritated with Polidori’s strange mix of puppy-like idol worship, immaturity and over-sensitive arrogance. Byron gave him the effeminate nickname Pollydolly, an insult which – considering Polidori was likely in love with him – must have stung.

Even before they left England, Byron began to humiliate his physician. Some of the poet’s friends came to see him off at Dover. As they ate dinner, Byron – to howls of laughter – lampooned a play Polidori had written. John stormed off and furiously paced the town’s streets. Upon reaching Belgium, Polidori was still able to write to his sister claiming, ‘I am with him on the footing of an equal’. But – as they journeyed across Europe – Byron would grow more and more exasperated with Polidori’s travel sickness, tantrums, back answers and sulks.

‘Pray, what is there excepting writing that I cannot do better than you?’ Polidori asked Byron in an inn overlooking the Rhine.

‘There are three things,’ Byron replied. ‘First, I can hit with a pistol the keyhole of that door. Secondly, I can swim across that river to yonder point. And thirdly, I can give you a damn good thrashing.’

Polidori also felt Byron outshone him. John observed Byron’s charisma sucking people into the poet’s orbit while he remained ‘like a star in the halo of the moon, invisible.’ Polidori’s own sense of self was being overshadowed by Byron. He would increasingly keep his distance from the poet and in June he half-heartedly attempted suicide.

Others had complained of Byron draining the life from them, eclipsing their personalities with his almost supernatural magnetism. Amelia Opie, a woman Byron had charmed, accused him of having ‘such a voice as the Devil tempted Eve with; you feared its fascination the moment you heard it.’ The critic Thomas Jones de Powis claimed Byron had ‘the facility of … bringing the minds of his readers into a state of vassalage or subjection.’

At the Villa Diodati, things deteriorated further. Polidori was thrown into jealous rages by Claire’s flirtations with his employer. He was also envious of the intense friendship Byron struck up with Shelley. After Polidori lost a boat race to Shelley, he challenged him to a duel. Shelley just laughed in the doctor’s face while Byron offered to fight the duel on his friend’s behalf.

The tensions in the Villa Diodati spelled the end of Byron and Polidori’s relationship and Polidori was soon sacked. As he began to write The Vampyre, Polidori is likely to have been brimming with rage, hatred, disillusionment and the pain of rejection. The temptation must have been great to satirise his famous employer and The Vampyre is – at least in part – a work of revenge. While it’s difficult to be sure how much Polidori knew about Byron, parts of the poet’s life and personality do appear to have influenced the reprehensible character of Lord Ruthven. By extension, these aspects of Byron’s history and temperament have formed much of our modern image of the vampire.

The Transgressive, Gothic and Vampiric Life of Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron was born in London in 1788. He emerged into the world shrouded by a caul. According to the folklore of many countries, those born in the caul – a phenomenon which affects less than one in 80,000 babies – are lucky and destined for greatness. The caul’s superstitious associations are, however, not always positive – in Romania those born in the caul become vampires after death.

Byron was also born with a club foot – a deformity that would make him walk with a slight limp, make physical activity difficult and perhaps give him an urge to prove himself.

For one upon whom much of the modern archetype of the vampire would be based, Byron had a suitably gothic childhood. When Byron’s great uncle – the ‘Wicked’ Lord Byron – died in 1798, Byron inherited his title along with the ancestral home of Newstead Abbey in Nottinghamshire: a dark draughty mansion with a ruined gothic monastery incorporated into its structure. Byron’s nurse, May Gray, gave him savage beatings and locked him in the dark after delivering terrifying lectures on religion and hellfire. Gray also led Byron to believe Newstead was haunted and she may have sexually abused him.

Newstead Abbey, Lord Byron’s ancestral home

Byron’s education was sporadic and eclectic, but he was eventually sent to school at Harrow. Byron – frequently in trouble with the teachers and alienated from most pupils – at first hated the place. He’d sneak out and spend hours lying dreamily on a flat gravestone, known as the Peachey Tomb, in nearby St Mary’s Churchyard. Though Byron never really settled at Harrow, his time there wasn’t completely wasted as he’d occupy himself by reading books of history, biography, philosophy – and poetry. He’d often recite their contents for his friends. In addition, Byron had a more unusual way of entertaining his schoolmates. Having discovered a human skull in the depths of Newstead Abbey, he’d drink from it in front of friends who visited him at home before urging them to do the same. At Harrow, Byron also made early forays into composing verse.

Lord Byron’s skull cup (Photo: devonlive)

After leaving school, Byron studied at Cambridge. Unimpressed, he wrote, ‘It is the Devil or at least his principle residence. They call it the University, but any other appellation would have suited it better.’

He also stated, ‘Since I have left Harrow, I have become idle and conceited, from scribbling rhyme to making love to women.’

Vampires are often seen as destroyers of boundaries and upsetters of the social order – transgressing the borders between life and death, callously smashing all rules of civilised behaviour and violating vows of marriage and betrothal (think of Dracula’s attentions towards Lucy Westerna and Mina Harker). The most ‘vampiric’ facet of Byron’s character was perhaps his tendency to blatantly disregard the conventions and restrictions of ordinary life and to even view them with contempt.

An amusing example of this attitude occurred during Byron’s time at Cambridge. When told he couldn’t keep a dog in his room, his response was to acquire a different pet – a bear. As the regulations made no mention of bears, the university had to accept Byron’s unusual roommate. Byron even threatened to apply for a college fellowship for the creature. Visiting Byron in Italy, Shelley remarked on his fondness for keeping an eccentric array of animals:

‘Lord B.’s establishment consists, besides servants, of ten horses, eight enormous dogs, three monkeys, five cats, an eagle, a crow and a falcon; and all these, except the horses, walk about the house, which every now and then resounds with their unarbitrated quarrels … [P.S.] I find that my enumeration of the animals in this Circean Palace was defective … I have just met on the staircase five peacocks, two guinea hens and an Egyptian crane.’

The Peachey Tomb, in St Mary’s Churchyard, Harrow, upon which Byron would lie as a schoolboy. Maybe the railings are to stop others following his example.

But it was for his defiance of sexual mores that Byron became most infamous. He almost certainly indulged in same-sex activity when at Harrow, something that appears to have been quite common despite the horror with which society at that time regarded such relations. Byron seems to have had an affair with a boy at Harrow called John Thomas Claridge and a liaison at Cambridge with one John Edleston, memories of whom would inspire several poems.

Byron went on to have numerous liaisons with married women, perhaps most notoriously with Lady Caroline Lamb. An Anglo-Irish aristocrat and wife of the future prime minister Viscount Melbourne, Lady Caroline claimed to have coined the famous description of Byron as ‘mad, bad and dangerous to know’. When Byron ended their relationship, Caroline suffered a mental derangement, stalking Byron and once even sneaking into his home disguised as a page boy, a scandalous move that could have meant the social ruin of them both. Caroline lost so much weight during her distress that Byron complained he was ‘haunted by a skeleton’.

Lady Caroline got her revenge by satirising Byron in a ‘kiss and tell’ or – as the poet put it – ‘fuck and publish’ novel called Glenarvon. The novel’s brooding anti-hero – who roams ruined priories, howls at the moon and dresses as a monk – betrays every person close to him. Aided by his demonic charisma, on a grand tour of Europe he ruins every woman he meets, some of whom end up dead. He is eventually confronted on a ship by the ghosts of all the women he’s destroyed. Overcome with remorse, he leaps into the sea.

Byron had many other liaisons: with female admirers, as well as with an assortment of actresses, servant girls and prostitutes. Typical of Byron’s attitude was a note he wrote casually to his publisher: ‘Last night I had Angelina, the daughter of my physician and a married woman.’

In 1812, the first two cantos of Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage were published. This semi-autobiographical travelogue-poem – suffused with sex, danger and adventure and based on a two-year trip Byron had made around Europe – brought Byron unimaginable attention and fame. At just 24 – in a society with little experience of stardom – he became the first modern celebrity. Byron was invited to dazzling parties and elected to exclusive social clubs, becoming – as the Fragment puts it – ‘deeply initiated into what is called the world’. He frequented the most fashionable drawing rooms of Regency London and fans mobbed him in the streets.

Despite this success, Byron projected a sullen image, making him seem similar to Childe Harold, the world-weary and melancholic hero of his poem. This may have been partly due to Byron’s club foot making him reluctant to dance. But standing sulkily on the edge of the dancefloor only enhanced Byron’s appeal. He was inundated by hundreds of letters from women eager to meet him. At one point, it even became too much for Byron’s gargantuan sexual appetite and he pleaded with his publisher to protect him from women’s advances. In a preface to The Vampyre, Polidori mentions a woman fainting just because Lord Byron entered the room. (The Vampyre is, in part, a satire on the vampiric nature of the new phenomenon of fame.)

Byron struggled with the blurring of his ‘real self’, his public personality and his creation Childe Harold. Acquaintances recalled Byron laughing and joking before abruptly switching to his moody persona if there were people around who expected it. ‘Why don’t you just be more natural?’ they’d ask him. ‘This is natural,’ he’d reply. As well as Byron’s persona overwhelming others, it seems to have sometimes oppressed and confused him. This powerful archetype – the aloof, prickly, enigmatic, inwardly tortured ‘Byronic hero’ – would influence future literary characters such as Heathcliff, Mr Rochester and Count Dracula as well as perceptions of rock stars like Jim Morrison.

After a while, however, there was a sense that Byron was going too far in his outraging of public decorum. This was in part because the laid-back Regency world was starting its transition towards a stricter, Victorian-style morality, but it was also due to Byron’s determination to go well beyond the flirtations and aristocratic affairs common in his milieu.

In January 1815, Byron married Annabella Milbanke, a sober serious person who happened to be Lady Caroline’s cousin. The marriage appears to have been doomed from the start – waking with a horrendous hangover in a carriage after the wedding reception, Byron saw light flickering through the dark red curtains and thought he was in Hell. It seems Byron had proposed to Annabella in the hope her wealth could pay off the debts he’d accumulated through extravagant living though it later turned out she was less wealthy than he’d assumed.

Byron’s marriage was marked by black violent moods, heavy drinking and affairs. Though unhappy marriages and adulterous liaisons weren’t considered unusual or especially shocking at the time, it was the way Byron went about undermining his union that appalled society. Rumours were soon flying around that he was having an incestuous affair with his half-sister, Augusta Leigh, an affair that may have been going on for a year before Byron’s marriage began. Byron does seem to have been obsessed with Augusta, writing of her: ‘I am much afraid that that perverse passion is my deepest.’ Byron might well have been the father of (the already married) Augusta’s third daughter Elizabeth Medora Leigh.

Gossip was also going round accusing Byron of sodomy, with both men and women. Sodomy was seen as an atrocious crime and those found guilty of it were hung on separate gallows so they wouldn’t ‘pollute’ the other convicts. As the rumours about Byron became more and more extreme, the press compared him to the decadent Roman emperors Nero and Caligula and alleged he’d seduced three boys while at Harrow. Byron felt he had no option but to flee England. He would never return alive.

The trauma of scandal didn’t encourage Byron to amend his behaviour. Upon reaching the Continent, he claimed he ‘fell like a thunderbolt upon a chambermaid’ in Ostend and he sent back to England for ‘more cundums’ while travelling along the Rhine. When news got round that Byron had hired out the Villa Diodati, the nearby Hotel Angleterre rented binoculars to English tourists so they could spy on the escapades of the notorious poet and his circle.

After leaving the Villa, Byron headed for Milan then moved on to Venice, where he is said to have seduced 200 women. Settling in that decadent decaying city, he had affairs with married aristocrats. Shelly visited him in Venice and what Shelley witnessed would prove too much even for that outspoken advocate of free love. Shelley stated that Byron ‘associated with wretches that seem to have almost lost the gait and physiognomy of man … he was familiar with the lowest sort of woman, the people his gondoliers pick up in the street. He allows fathers and mothers to barter with him for their daughters.’

So How Did The Vampyre Reflect Byron’s ‘Debauchery’, ‘Wickedness’ and ‘Baleful Influence’ upon Others?

Polidori’s character of Ruthven is, of course, based on Byron. Ruthven is aristocratic and seems wealthy, though Aubrey would gradually learn ‘that Lord Ruthven’s affairs were embarrassed’ and that, because of this, ‘he was about to travel’. Ruthven is charismatic and good-looking: ‘In spite of the deadly hue of his face, which never gained a warmer tint … it’s form and outline were beautiful.’ Ruthven, like Byron, is a part of society but also a stranger in it. He’s cold, aloof, sexually alluring, and often violent and remorseless in the quest to fulfil his desires.

Travelling with Ruthven, Aubrey soon notices he seeks out ‘the centres of all fashionable vice’. Aubrey receives letters from his guardians in England warning him that ‘there was an evil power resident in his companion … that his character was dreadfully vicious, for that the possession of irresistible powers of seduction, rendered his licentious habits more dangerous to society.’ The letters tell Aubrey of a Dracula-style contagion of evil: ‘all those females who he had sought, apparently on account of their virtue, had, since his departure, thrown even the mask aside, and had not scrupled to expose the whole deformity of their vices to the public gaze.’

Lord Byron would influence the portrayal of vampires in literature and film.

Indeed, Byron’s aristocratic antics seem to have – at times – outraged the bourgeois morals of the middle-class Polidori. (In Dracula, Bram Stoker would favourably contrast the sober values of the middle-class characters with those of the flightier, more decadent – and, in the Count’s case, downright evil – aristocrats.) The Vampyre seems saturated by the bitterness that a famous aristocratic man can – at least for a while – get away with behaviour that his ‘social inferiors’ would have been unable to.

Polidori also underlined how dangerous Ruthven (or Byron) could be. While Ruthven would not give any charity to the virtuous who ‘were sent from the door with hardly suppressed sneers … when the profligate came to ask something, not to relieve his wants, but to allow him to wallow in his lust, or to sink him still deeper in his iniquity, he was sent away with rich charity.’ But ‘all those upon whom it was bestowed, inevitably found there was a curse on it, for they were all either led to the scaffold or sunk to the lowest and most abject misery.’

Byron himself felt he was cursed, noting that many of his friends, lovers and acquaintances suffered misfortune or died tragic and early deaths. Lady Caroline Lamb, for instance, never recovered from her liaison with Byron. Following struggles with mental instability, health problems and addictions to laudanum and alcohol, she passed away at just 42. Caroline has her anti-hero in Glenarvon proclaim, ‘Weep! I like to see your tears; they are the last tears of expiring virtue. Henceforth, you shall weep no more … My love is death!’

Lord Byron’s ‘vampiric curse’ – it might seem – also worked its influence on those who’d been with him in the Villa Diodati. All of them would experience tragedy or in some way be afflicted by premature death. Byron’s ‘curse’ would – especially – overshadow what remained of the life of John William Polidori.

The Publication of The Vampyre and the Final Tragedy of John William Polidori

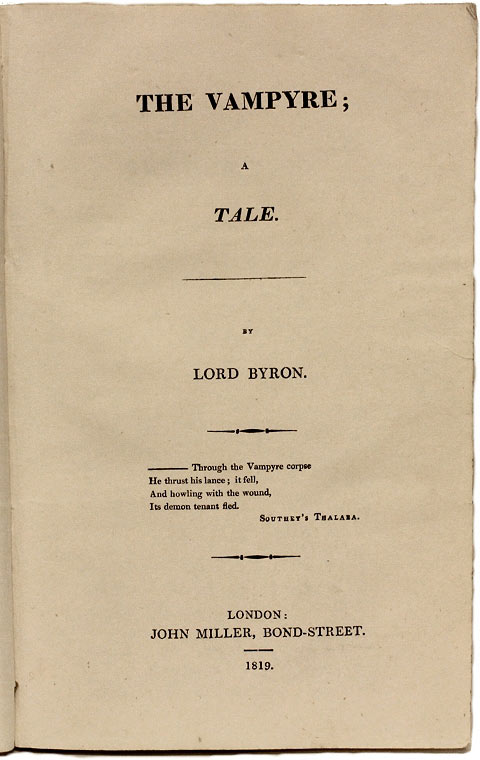

After his sacking by Byron, Polidori travelled around Italy before returning to London. It was there, while living in Soho, that he was shocked to learn The Vampyre had been published. The work appeared – without Polidori’s permission – on April Fools’ Day (1st April) 1819 in The New Monthly Magazine. A far worse insult was that it was entitled: The Vampyre: A Tale by Lord Byron.

Polidori scrambled to assert his rights to the novella. Despite repeated denials by Byron and Polidori, the idea of Byron’s authorship prevailed for quite a while and – when Polidori succeeded in making enough noise to draw attention to himself – he was accused of plagiarism or piggybacking on Byron’s fame. Later the same year, The Vampyre came out in book form and was also attributed to Byron though later editions did exchange his name for Polidori’s. Byron’s Fragment got published too in an attempt to clear up the confusion, but The Vampyre continued to be viewed by many as the creation of Polidori’s ex-boss.

Polidori had left his manuscript at the home of his friend Countess Bruess, where it had lain around for three years before the Countess passed it to a Madame Gatelier. Madame Gatelier forwarded the novella to the disreputable journalist and publisher Henry Colburn, who had put out Glenarvon and would publish Frankenstein. Colburn had the story printed up in The New Monthly Magazine. In a typically offhand manner, Byron dissociated himself from Polidori’s work: ‘If the book is clever, it would be base to deprive the real writer, whoever he may be, of his honours; and if stupid, I desire the responsibility of nobody’s dullness but my own.’

The Vamprye, however, proved an immediate hit, partly because of the attribution to Lord Byron, partly because it fitted the public’s enthusiasm for gothic horror tales. The book went through numerous editions and translations. A play based upon it – Le Vampire, which premiered in Paris in June 1820 – was immensely popular and ignited a vampire craze across Europe. Operatic adaptations were made of Polidori’s story and Nikolai Gogol, Alexandre Dumas and Aleksey Tolstoy would all produce vampire tales. The modern archetype of the vampire had been born.

An early edition of The Vampyre, credited to Lord Byron rather than Polidori

Little of the praise or money The Vampyre generated found their way to Polidori. Though he wrote other novellas, plays, non-fiction books and poems – including a long theological poem called The Fall of the Angels – none of these works gained success and Polidori became more and more disgusted with the literary world. Searching around for a new purpose, Polidori even sought to return to Ampleforth College to train as a monk. Polidori’s request was refused, with the prior telling him this was due to ‘certain publications which I have seen and of which I must tell you as a friend I wish you had not been the author.’ Even though Polidori had abandoned his literary dreams, he couldn’t free himself from Byron’s spectre. Polidori enrolled to study law – using his mother’s maiden name – but could muster no enthusiasm for it. He fell into depression and gambling addiction, amassing large debts.

Polidori died in London on 24th August 1821, two weeks short of his 26th birthday. While he almost certainly committed suicide – by ingesting prussic acid – the coroner gave a verdict of death by natural causes, probably out of consideration for Polidori’s family.

‘Poor Polidori,’ Byron wrote upon hearing the news, ‘it seems that disappointment was the cause of this rash act. He had entertained too sanguine hopes of literary fame.’

Even in death ‘poor Polidori’ was unable to summon the respect he had craved. He was buried in Old St Pancras Churchyard, London, but his grave was one of 7000 interments dug up to make space for a railway in the 1860s. The architect put in charge of this gruesome job was the young Thomas Hardy. While Hardy had the human remains carted offsite and buried in a pit, he came up with a novel solution about what to do with the hundreds of redundant gravestones. He massed the tombstones together in a circle and planted an ash tree in the centre of that macabre ring. As the ash – known as The Hardy Tree – grew, it absorbed many of the gravestones: forming an interesting tableau demonstrating the complex intermixture of life and death. An appropriate memorial, perhaps, to one who added so much to the myth of the vampire.

The Hardy Tree, in Old St Pancras Churchyard. Is Polidori’s gravestone one of those massed around it? (Photo: theprogressiveaspect)

The ‘Curse’ of the Vampiric Lord Byron

Polidori wouldn’t be the only one from the Villa Diodati affected by Byron’s ‘curse’. In July 1822, Percy Bysshe Shelley drowned in a boating accident off the Italian coast, less than a month before he turned 30. Shelley had named his boat – a ‘perfect plaything for the summer’ – the Don Juan as a tribute to one of Byron’s best-known poems. When Shelley washed up on a beach near Viareggio, his body – in keeping with quarantine regulations – had to be burnt there.

Byron, along with Shelley’s friend Edward Trelawny, carried out the grim task of building the pyre and setting the fire going. But, as the flames began to consume Shelley, Byron – bizarrely – stripped off and swam out to sea, thereby missing most of the cremation. He may not have been able to bear the scene for long as parts of Shelley’s corpse had been fleshless when the ocean gave him up. A book of Keats’ poems was found in Shelley’s pocket and Trelawny is said to have snatched his heart from the blaze. Years later, after Mary Shelley’s death, her son discovered the remnants of a charred heart in a drawer.

A 1889 painting of the funeral of Percy Bysshe Shelley. This romanticised depiction, by Louis Edouard Fournier, contains a number of historical inaccuracies.

Mary Shelley died at 53. Though Frankenstein was well-received, she doesn’t seem to have garnered much money from it. During her financially precarious life, she would – however – write many more books and put a great deal of energy into editing her husband’s work and promoting his reputation as a great poet.

Claire Clairmont – mostly working as a governess – lived in several European countries, eventually dying in Italy at 80 years of age. Her daughter Allegra – who she’d been carrying at the Villa Diodati – was taken from her by Byron. Placed in an Italian convent against Claire’s wishes, Allegra died at five. Her body was brought back to England and buried in St Mary’s Churchyard, Harrow, close to the Peachey Tomb upon which Byron had dreamed away so many adolescent hours. Claire blamed Byron for Allegra’s death and hated him for the rest of her life. She’d say her relationship with the poet had given her just a few moments of pleasure but a lifetime of trouble.

Byron himself travelled to Greece, where he joined that country’s armed struggle for independence from the Ottoman Empire. Now balding and white-haired, Byron fell in love with a Greek youth called Lukas Chalandritsanos. Byron’s legendary charms, however, were on the ebb – despite writing poems for Chalandritsanos and spending large sums upon him, the poet’s affections went unreciprocated.

Byron died from a fever on 19th April 1824, aged 36. Some say his heart was cut out and kept in Greece – where he was, and still is, a national hero – but his body was embalmed and returned to England. Byron was to have been buried in Westminster Abbey, but the clergy challenged this plan on the grounds of his ‘questionable morality’. Death had not, however, diminished Byron’s fame and huge crowds viewed his coffin as he lay in state for two days in London. Byron was interred in his family vault in St Mary Magdalen’s Church, Hucknall, Nottinghamshire.

Lord Byron on his Deathbed, painted in 1826. Note the sheet covering Byron’s club foot.

There is, though, an interesting postscript to Byron’s story, a postscript suggesting that even death and the passing of more than a century couldn’t extinguish his vampiric sexual charisma. In 1938, the vicar of Hucknall – because of persistent rumours that Byron’s coffin was empty – agreed to have his casket opened. Inside was Byron’s well-preserved – and naked – corpse. The vicar stated:

‘Reverently, very reverently, I raised the lid and before my eyes lay the embalmed body of Byron in as perfect condition as when it had been placed in the coffin … his features and hair easily recognisable from the portraits with which I was so familiar. The serene, almost happy expression on his face made a profound impression on me … I gently lowered the lid of his coffin – and as I did so, breathed a prayer for the peace of his soul.’

The coffins of Lord Byron and his only legitimate daughter Ada Lovelace. The crowns show their status as barons.

The vicar’s churchwarden, however, couldn’t help remarking that Byron’s ‘sexual organ showed quite abnormal development’. One of the workmen who’d helped them lever open the coffin was far blunter. He said Byron was:

‘Just like in the portraits … a good-looking man putting on a bit of weight, he’d gone quite bald. He was quite naked, you know … look, I’ve been in bathhouses, I’ve been in the army, I’ve seen men. But I never saw nothing like him. He was built like a pony.’

(The article’s main image shows an 1813 portrait of Lord Byron in traditional Albanian dress.)

Hello,

just wanted to let you know that this was a fascinating read, thank you so much for this priceless resource!

Thanks so much, Linda – glad you enjoyed the tales of Byron, Polidori and the vampire!

Fantastic article – Polidori’s life story is as interesting as the actual novella he wrote! Going to get my daughter to read this for English Literature A-Level supportive information and putting the Hardy Tree on my list of places to visit in London. Thank you.

Thanks so much, Kate, glad you enjoyed it. I think that set of writers – Byron, Shelley, Mary Shelley, Polidori – did have lives as interesting, and as tragic, as the literature they wrote. And I’m somehow not surprised Byron turned out to be the model for the aristocratic vampire!

This was such a thorough and interesting read! Many thanks for writing this and sharing all of this knowledge.

Thanks for this interesting and enjoyable portrait of this famous group from villa diodati. You captured the genius and continuance of their lives and art. Great artists influence and inspire each other.

Thanks for this interesting and enjoyable portrait of this famous group from villa diodati. You captured the genius and continuance of their lives and art. Great artists influence and inspire each other.

Such an interesting article!

Thanks, Sarah!

Thank you! Your writing style is very pleasant to read, as is your article!

I am very interested in the life of John Polidori, I even played his role once at university and now I’m dealing with some work related to him and Byron’s company, so yes, every small detail of their past is so important to me and I’m so grateful that such articles exist. All of Polidori’s works are fascinating! And I totally agree with you that all of them had lives as interesting, and as tragic, as the literature they wrote.

But honestly I still wonder why some consider John to be gay or bisexual… Some on the contrary even think that he fell in love with Mary. Do you happen to know where one can find out more about this? Or do you have any thoughts on this? I am interested in the sources of such assertions.

Thank you very much anyway!

Hi Simon, thanks for your comment. I’m so glad you enjoyed the article. I can’t remember offhand exactly where I read about John’s sexuality, but most of the sources I consulted did suggest he was gay or bi and in love with Byron. The idea he might have (also) been in love with Mary makes the whole situation even more intriguing! Many thanks, David.