One night in 1713, the Italian violin maestro Giuseppe Tartini had the strangest dream. He dreamt the Devil appeared and offered to be both his servant and master. Seduced by such a prospect, Tartini had no hesitation in selling Satan his soul.

The Devil asked Tartini to give him a music lesson, which the maestro did, demonstrating to the Evil One the magnificent skill he’d built up through years of learning, practice and performance. Tartini then passed the Devil his violin to see if the Fiend could reproduce any of what he’d been taught.

The Devil confidently took up the instrument and Tartini was astounded when he began to play with incredible virtuosity, delivering a performance which was powerful and intense, but exquisitely tasteful and executed with the most breath-taking precision. The Devil’s playing easily surpassed even Tartini’s brilliance. Tartini stared at the Fiend, his mouth dropped open, time seemed to halt as the most amazing music poured from the violin.

The story is recounted in Giuseppe Tartini’s own words in Jerome Lalande’s book Voyage d’un François en Italie (1769):

‘One night I dreamed I had made a pact with the Devil for my soul. Everything went as I wished: my new servant anticipated my every desire. Among other things, I gave him my violin to see if he could play.

How great was my astonishment on hearing a sonata so wonderful and so beautiful, played with such great art and intelligence as I had never even conceived in my boldest flights of fantasy. I felt enraptured, transported: my breath failed me and I awoke.’

But how did this nocturnal vision affect Giuseppe Tartini? Was his experience of soul selling merely a bizarre dream or did it spill over into his waking life, adding a sulphurous tinge to his music? And is there any evidence Tartini genuinely entered into a diabolical pact, bartering his soul for success, fame and musical mastery?

Giuseppe Tartini Tries to Recreate the Devil’s Fiendishly Good Composition

The moment he woke up, Tartini reached for the violin lying by his bed, eager to recreate the Devil’s tune. Tartini was probably in that state in which the worlds of wakefulness and dream mingle, in which sleep’s fantastical logic floats above the solid and prosaic. With the Devil’s notes echoing faintly in his head, Tartini’s drowsy fingers fumbled on the strings as he strove to delve back into his dream.

However, as Tartini put it, his attempts were ‘in vain! The music which I at this time composed is indeed the best I ever wrote … but the difference between it and that which so moved me is so great that I would have destroyed my instrument and said farewell to music forever if it had been possible for me to live without the enjoyment it affords me.’

Out of his efforts to remember the diabolically brilliant tune, Tartini did produce an impressive – and technically demanding – piece of music: his Violin Sonata in G Minor, otherwise known as the Devil’s Trill Sonata. But while – from the hundreds of compositions he wrote in his lifetime – this piece would remain Tartini’s favourite, he felt it was ‘so inferior to what I heard that, if I could have subsisted by other means, I would have broken my violin and abandoned music forever.’

Tartini’s Devil’s Trill Sonata was apparently just a pale reflection of the music Satan played in the violinist’s dream.

The Devil’s Trill Sonata (Violin Sonata in G Minor)

Lasting around 16-and-a-half minutes, the Devil’s Trill Sonata contains three movements and boasts haunting and expressive melodies.

The sonata is below so – if you dare – you can have a listen. As someone relatively unschooled in classical music – and knowing next to nothing about the violin – I’m going to try to describe how this piece strikes me on a simply emotional level.

The Devil’s Trill Sonata starts off gently, with sombre tones evoking a beautiful desolation. Sweeping chords – mournful yet bewitching – resonate soulfully. There’s something heart-breaking here, a sweetly bitter nostalgia. But now there’s fast high-spirited playing, like notes are springing, jumping, twisting in the air. We hear a certain hope, a lightness, the joy of expectation as notes skip and dance around one another. Yet darker shades creep in, perhaps there’s some foreboding or fear of failure amongst the longing and glee.

As the Devil’s Trill Sonata goes on, emotions conflict. Dark tones intrude upon wistful memories; sinister surges overwhelm sweet recollections. The despondency’s getting deeper, as if there’s – sometimes – an acceptance of some dolorous fate, as if the violin’s sobbing. But an echo of thunder now grows. Something’s gathering energy, mounting chaotically to a discordant peak before taking a plunge into melancholy. It’s heart-rending, as if you know something wonderful has been lost and can never be recovered.

The violin continues with its dirge then things briefly liven up – is some hope rising? – before the sonata dips back into gloom. The violin laments darkly before cheerier notes once more leap – perhaps joyful memories are again being revived. These memories – these hopes – quiver before tumbling into a pit of anguished emotions: emotions that jar, that strive against one another. These quarrelling impulses grow quieter – as if they’re dropping deeper into darkness – before they struggle up to be heard more loudly again. Finally, the Devil’s Trill Sonata reaches a state of resignation, a resolution from which dolefulness overflows.

I can’t help feeling this sonata tells the story of the Devil himself. Satan was the highest, the most luminous, the most glorious angel in Heaven and was also – intriguingly – the angel in charge of music. But, according to the Bible and Christian folklore, Satan became swollen up with pride. He mustered an army of a third of Heaven’s angels and rebelled against God’s rule. God dealt swiftly the upstart and his minions, driving them out of Heaven with the help of his loyal angels, with the Archangel Michael brandishing a sword and chasing the Devil and his followers down to Hell. Banished forever to this infernal prison, cut off from all hope, severed from God’s love, the rebels face a bleak and tormented eternity.

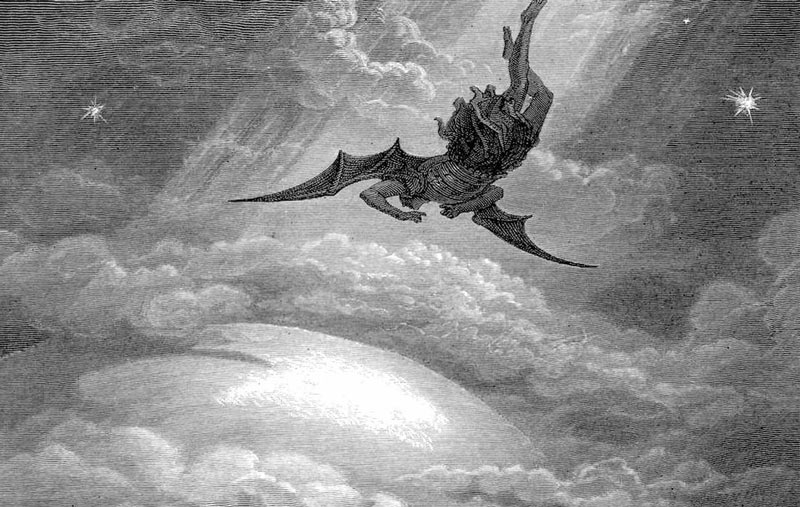

Satan falls after he is cast from Heaven, depicted by Paul Gustave Dore.

Maybe the melancholy at the start of the Devil’s Trill Sonata shows Satan lamenting his fallen state while the happier notes recall the joys of his magnificent old home in Paradise. Perhaps the leaping, athletic notes then take us back to the giddy hopes of Satan’s planned rebellion. Such notes, however, mingle with sombre tones, which could betray the dread of the revolt not working out. Then we have the thunderous fall – representing the driving of Satan and his supporters from Heaven – followed by more lamentations for what’s been lost, lamentations spiked with upsurges of misplaced hope. We experience the Devil’s inner strife – a struggling of anger, arrogance, self-pity and regret – before a tortured acceptance, brimming with sadness, ends the piece.

That’s my take on it, anyway. I apologise for any errors caused by my musical ignorance.

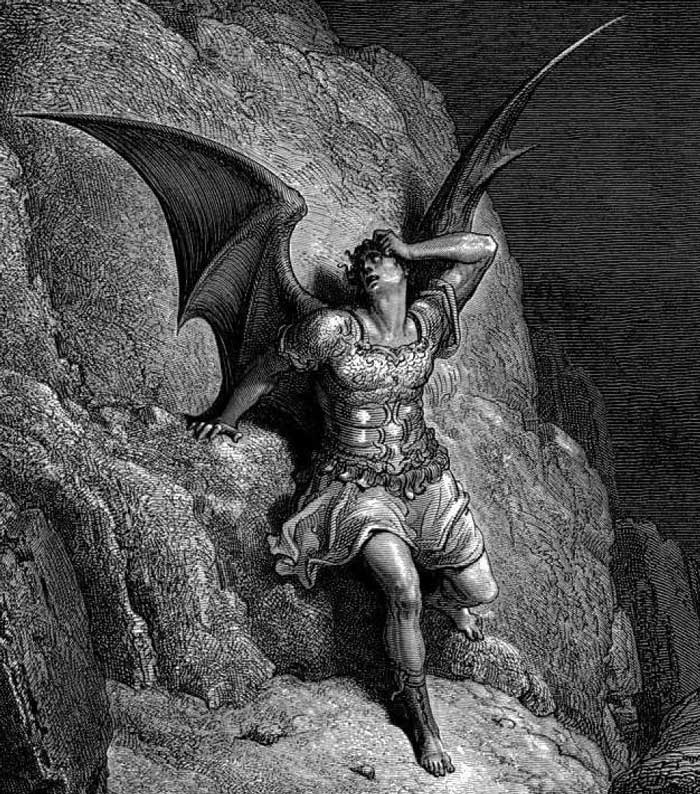

The Devil, to his horror, wakes up in Hell in an illustration by Paul Gustave Dore for John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

The ‘Suspiciously Successful’ Career of Giuseppe Tartini

As well as penning the Devil’s Trill Sonata – by any judgement an incredible piece of music – Tartini had a very successful life and career.

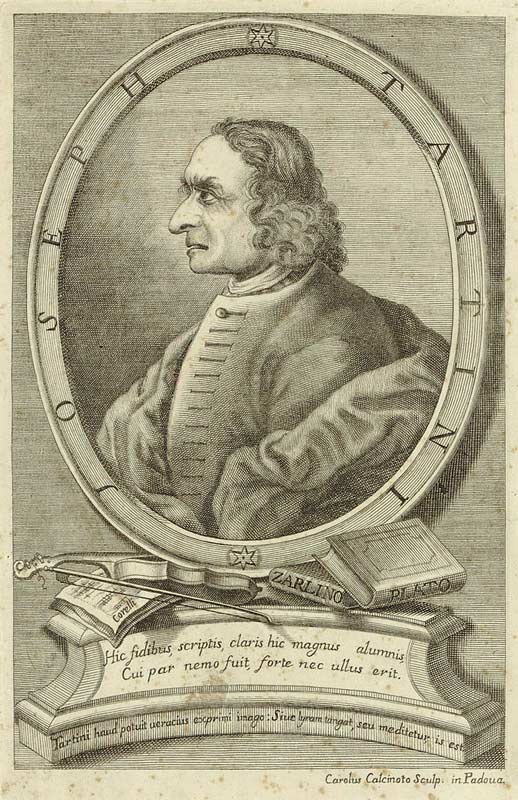

Giuseppe Tartini was born in 1692, in the town of Pirano, in the Republic of Venice. After moving around between several Italian cities, he withdrew for a number of years of solitary study devoted to the violin, emerging with new thoughts on strings, the bow and bowing techniques, ideas which would have an enormous influence on generations of violinists.

Tartini’s playing emphasised both technical mastery and poetic, emotional nuances. It was claimed Tartini produced a magical impression on his audiences, helping his fame spread across Europe.

At just 29, Tartini was appointed director of the orchestra at the Basilica of St Anthony in Padua, a position he retained for the rest of his working life. He played for emperors and nobles, composed for the Pope, and set up a violin school which drew students from many countries.

Proclaimed by the Italians as ‘the finest musician in the world’, he was referred to by the French as ‘the lawgiver of the bow’, and it was said ‘he doesn’t play, he sings on the violin’. In addition to his musical achievements, Tartini seems to have burned with a Faustian desire for knowledge – he owned an impressive library containing books on many subjects, and was intensely curious about philosophy, religion, harmonics, acoustics and mathematics. Giuseppe Tartini died in 1770.

Giuseppe Tartini, depicted with his violin and books

So, Giuseppe Tartini enjoyed a life enchanted by a dazzling talent. His was a life animated by an almost demonic thirst for learning, a life garlanded by praise and crowned with the most astonishing success. A superstitious person – hearing about Tartini’s dream – might be tempted to think the Devil did appear to him that night and that Tartini really did agree to exchange his soul for such gifts.

Tartini is far from the only musician suspected of making a diabolical transaction of this type. To examine whether Tartini’s triumphs might have been granted by the creature that manifested in his bedroom, let’s compare his story with the legends of some other musical soul sellers.

How Might Giuseppe Tartini Fit into the History of Devil-inspired Musicians and Soul Sellers?

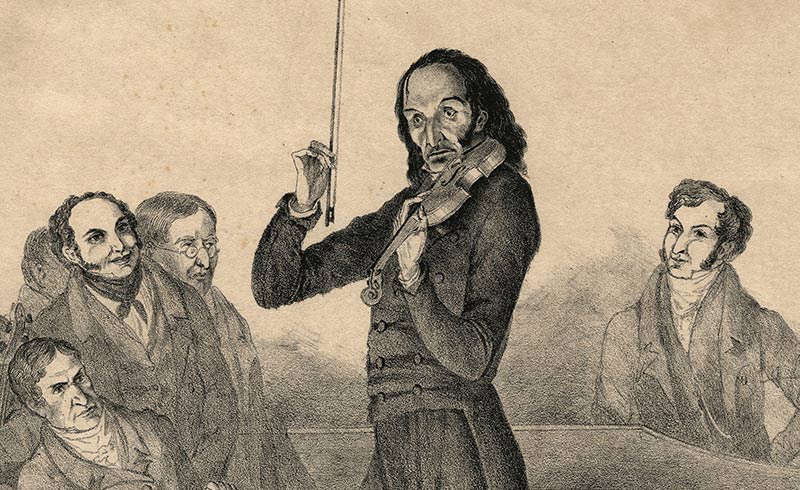

Other characters in musical history have been linked with soul-swapping legends. One individual alleged to have struck a demonic deal was the virtuoso violinist Niccolo Paganini (1782-1840). Reports of Paganini – a gaunt pallid figure who often dressed in black – speak of his flaming eyes and of devils appearing onstage at his concerts. It was claimed he could play on broken strings or play 12 notes a second. During one performance, apparently, the Devil made lightning strike Paganini’s bow. Following Paganini’s death, it took the Church 36 years to allow him burial in consecrated ground.

The violin virtuoso Niccolo Paganini was rumoured – like Tartini – to have sold the Devil his soul.

Another famous soul seller was the American bluesman Robert Johnson (1911-38), who – according to legend – walked to a Mississippi crossroads with his guitar on his back to meet the Devil at midnight. Standing in the darkness, Johnson played a tune. A finger tapped his shoulder and he handed his guitar to the Evil One, who also gave a brief – and no doubt brilliant – performance. The Devil handed the instrument back and the pact for Johnson’s soul was sealed. Modern musicians – like Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page – have also been accused of participating in diabolical bargains.

Maybe people suspect incredible talent or virtuosity must have superhuman origins. Perhaps this is especially so in music, given the Devil’s longstanding connection with this area of the arts. Such tales may also reflect a longing on the part of creative people themselves to overcome the sheer hard work, the frustrations, the wrong turns, the inevitable imperfections that bedevil (pun intended) the creative process, to overcome them and produce that elusive work of shimmering excellence.

Another supposed soul seller was the brilliant bluesman Robert Johnson.

But Tartini’s story doesn’t fit neatly into this narrative. With the musicians mentioned above, rumours of their devilish pacts were circulating while they were at the summit of their careers. There’s evidence Robert Johnson even encouraged the gossip about his demonic deal to boost his emerging fame. As we’ll see below, it was different with Tartini.

It Took Tartini Years to Confess to His Diabolical Dream

Tartini – a reserved and serious-minded person – kept his encounter with the Devil secret for a long time. He didn’t tell anyone about his dream until he gave an interview to the French astronomer Jerome Lalande a few years before he passed away. Lalande included it in his book Voyage d’un François en Italie, published in 1769. Also, the sheet music for the Devil’s Trill Sonata wasn’t published during Tartini’s lifetime. It only appeared in 1798, almost three decades after his death. It’s said to have been discovered in Rome by the French violinist Pierre Baillot, who brought it to Paris in 1791.

So Tartini didn’t reveal the story of his dream until shortly before he died and didn’t seem to want to publicise the Devil’s Trill Sonata. This is despite believing it was the best piece he’d ever composed. Tartini wrote at least 200 sonatas and concertos, many of which he had no hesitation about putting into print.

Tartini may have wished to keep his strange experience secret from his employers at St Anthony’s, churchmen who would have disapproved of him interacting with the Devil, even in a dream. He may also have feared ridicule, religious scandal and the resulting loss of reputation or livelihood. But, perhaps, recognising his life was approaching its end and having retired from St Anthony’s, he didn’t want the story to be lost.

It’s interesting that Tartini chose an astronomer to confide in about the Devil’s Trill Sonata. He’d been corresponding with scientists from a number of fields for several years and he might have preferred to narrate his incredible tale to a level-headed man of science rather than an overly romantic artist or dogmatic priest. There was also the advantage that – since Lalande was French – the book would be published in a foreign country and language, delaying the impact of any controversy.

Did Giuseppe Tartini Really Sell the Devil His Soul in Exchange for Musical Brilliance?

It’s unlikely that Tartini believed he’d sold his soul. By his own admission, his Devil’s Trill Sonata was just a pallid copy of the jaw-dropping music Satan had played. This suggests that – even if one were to believe in such possibilities – the soul-trading ceremony just took place in Tartini’s dream and wasn’t enacted in the waking world. There’s no indication of Faustian contracts signed in blood and – while Tartini considered breaking his violin in frustration – there’s no evidence he thought of summoning Satan back to trade in his soul.

In addition, although Lalande claimed Tartini composed the Devil’s Trill Sonata in 1713, musical historians feel that – due to its stylistic innovations – it couldn’t have been written before about 1745, years after Tartini began to enjoy success. This would remove any need for Giuseppe Tartini to make a career-boosting pact with Satan. (Unless, of course, we assume the Devil enabled Tartini to make a musical leap many years ahead of his time.)

There is, nevertheless, something uncanny about the piece that emerged from Tartini’s dream – the wrenching depths of emotion that it enables a wooden box and four strings to convey, the way it transports you somewhere a little different, the unsettled feeling you have after hearing it. There’s something unusual, perhaps creepy there, as Tartini himself recognised.

Interestingly, a curious annotation appeared in the earliest printing of the Devil’s Trill Sonata. At the place in the third movement where the Devil’s Trill itself begins, there’s a note that states: ‘The Devil at the foot of the bed’.

The Devil’s Trill Sonata with the note ‘the Devil at the foot of the bed’. Did Tartini write this comment?

This note evokes images of Satan appearing to a nightcapped Tartini, perhaps in a cloud of sulphur-tainted smoke. While it’s not certain that Tartini wrote this comment, we know Tartini did annotate his manuscripts. He tended to do so in code, scribbling bits of secular poetry in their margins. The fact he wrote in code shows both his concern for privacy and perhaps a worry that his ecclesiastical employers might disapprove of some of his sentiments. The statement about the Devil, however, is not encoded. Could Tartini – if it was indeed him who wrote it – have never intended this chilling note to be glimpsed by anyone else? Could it be an acknowledgement – at least – of how much he was both shaken and inspired by his dream?

Whatever the truth might be, the Devil’s Trill Sonata has been influential in the history of music. The piece formed the basis for Chopin’s Prelude No. 27 and had a decidedly diabolical influence on Cesare Pugni’s 1849 ballet Le Violin du Diable (The Devil’s Violin).

Giuseppe Tartini may not have felt he did true justice to what he heard in his dream, but what he did manage to put together has been appreciated ever since and has left a whiff of brimstone wafting down the centuries.

(This article’s main image shows Tartini meeting the Devil in his dream and receiving the inspiration for his Devil’s Trill Sonata.)

Kept my eyes glues to the computer screen. The stories were already interesting enough, but the way you tell them gives them so much life. Thank you!

Many thanks, Evans, glad you enjoyed the tale of Tartini, the Devil and his violin. 🙂

Can anyone tell me how to deal with devil

Sorry, Ajinkya, I can’t claim to have access to such information. Maybe you have to wait for him to appear in your dreams.

This was beautifully written it was very informative and entertaining at the same time.

Thanks, Aaliyah, glad you liked the tale of Tartini’s ‘soul-selling’ violin genius!

So glad I found this blog, I read the story many years ago thinking that it was a Piano piece, and I decided to google it today so I found your article. Thanks!

Fascinating story. And wonderful renditions of The Devil’s Trill on You-Tube by various violinists, including Perlman and Heifetz.