Vampires tend to be associated with Central and Eastern Europe, but the tiny Cumbrian village of Croglin – around 14 miles south east of Carlisle and not far from the Scottish border – has long boasted a homegrown bloodsucker. This picturesque settlement, which lies between the Pennines and the River Eden, was once menaced by a beast that claimed many of the attributes of the classic vampire trope. This burning-eyed creature would stagger from a family crypt in a lonely churchyard, break into manor houses and plunge its teeth into the necks of young women, who would then have the weirdest urges to return to Croglin.

The Croglin Vampire is a strange tale of villagers breaking open vaults determined to destroy the beast, of vampiric bats flying out of churchyards, of ‘vampiric corpses’ burnt next to sacred holly bushes, of escaped asylum inmates, of bitter religious conflict, and of starving circus monkeys rampaging through the Cumbrian landscape. It’s also a tale that ends with a bricked-up window festooned with lucky horseshoes, an alteration designed to stop the entry of any similar creatures.

The tale of the Croglin Vampire was made known to the wider public thanks to its inclusion in Story of My Life, the autobiography of one Augustus Hare (1834-1903). A biographer, travel writer and raconteur, Hare felt his life’s story merited a whopping six volumes, which were published in two batches in 1896 and 1900. Hare – like many Victorians – was fond of a good ghost story and included plenty in his books. He claimed to have heard the fantastical account of the Croglin Vampire during an after-dinner chat involving a Captain Fisher-Rowe. Having impressed the assembled company by rattling off some of his eeriest tales, Hare was surprised when Fisher-Rowe responded with an even spookier story.

Fisher-Rowe stated that his family owned a large house named Croglin Grange and that the oddest legend was associated with it. After moving down to Surrey, the Fishers had let the Grange out. But one of their tenants – a young female – soon endured a petrifying ordeal. She found herself menaced by a vampire from a nearby churchyard – an incident that kicked off the most remarkable succession of events.

Claims have been made that the Croglin Vampire tale has over the years been embellished both by local folklore and excitable writers. A long series of researchers have queried, debunked and rehabilitated the legend then questioned it again. There have been accusations of plagiarism and of contamination from the copious gothic horror stories and penny dreadfuls clattered out by the printing presses of the vampire-obsessed Victorian age. Earnest investigators have spent days tramping over the bleak Cumbrian countryside, interviewing locals, searching for the remnants of chapels and poring over archives and property deeds.

The Croglin Vampire is indeed an elusive story. But let’s start with a summary of what’s alleged to have gone on, drawing mainly from Augustus Hare’s narrative with a little admixture from other accounts and from the folklore of the district.

The Truly Weird Tale of the Croglin Vampire

In Hare’s account, Captain Fisher begins by informing him that while ‘Fisher may sound a very plebeian name’ his family was ‘of a very ancient lineage, and for many hundreds of years they have possessed a very curious old place in Cumberland, which bears the weird name of Croglin Grange. The great characteristic of this house is that never at any period of its very long existence has it been more than one storey high, but it has a terrace from which large grounds sweep away towards the church in the hollow, and a fine distant view.’

Hare goes on to tell us that when ‘the Fishers outgrew Croglin Grange in family and fortune, they were wise enough not to destroy the long-standing characteristic of the place by adding another storey to the house, but they went away south, to reside at Thorncroft near Guildford and they let Crouglin Grange.’

Augustus Hare, who publicised the story of the Vampire of Croglin Grange

The Fishers were ‘extremely fortunate’ in the tenants they found – two brothers and a sister. Though Hare doesn’t name them, later sources give their surname as Cranswell, with the brothers called Edward and Michael and the sister Amelia. And while Hare doesn’t give a date for their tenancy, it’s been assumed they occupied the house at some point in the 1870s, as this was when the Fishers moved out.

The Cranswells loved living at Croglin Grange and soon made themselves popular in the surrounding area. Hare states that ‘to their poorer neighbours they were all that is kind and beneficent, and their neighbours of a higher class spoke of them as a most welcome addition to the little society of the neighbourhood.’

The Cranswells passed a winter and spring ‘most happily’ in Croglin Grange ‘sharing in all the little social pleasures of the district’ and found that the Grange, despite its unfortunate lack of a second floor, was ‘in every respect … exactly suited to them.’ During the summer, however, there came a day which was ‘dreadfully, annihilatingly hot’. The brothers could do nothing more active than lounging under trees reading books. Amelia positioned herself on the veranda and tried to work, though ‘in the intense sultriness of that summer day, work was next to impossible’.

After dinner, the siblings sat on the veranda, appreciating the evening’s slightly cooler air. Looking out over the grounds, towards the band of trees that separated the Grange’s lands from the adjacent churchyard, they watched the sun set and moon rise. Soon they were enjoying the sight of ‘the whole lawn … bathed in silver light, across which the long shadows from the shubbery fell as if embossed, so vivid and distinct were they.’

The Cranswells retired for the night, but Amelia found it too hot to sleep. Though her windows were closed, she hadn’t fastened the shutters, feeling that – in such a tranquil and unthreatening location – this wasn’t necessary. As she was unable to drop off, she just stared out at ‘the wonderful, the marvellous beauty of that summer night.’

After some time, though, she noticed a perplexing addition to the scene of moon-drenched gardens, trees and lawn. Two bright lights were flickering around the strip of trees close to the churchyard. Amelia found her gaze being drawn towards, being fixed on them. The lights soon stopped dodging in and among the tree trunks and started to advance across the lawn towards the house. Unable to stop staring at those eerie lights, Amelia released they part of some figure, a figure that – in a shambling walk – seemed to be heading in the direction of her window. Sometimes this being was obscured by the shadows of the trees, but the lights were always visible, getting closer and closer.

Amelia’s heart was now pounding, shivers were passing over her skin, and she knew she had to get away. The room’s door was, however, near the window that the beast was approaching and Amelia knew that unlocking it would put her closer to the creature for a moment. She wanted to scream, but her throat seemed paralysed, her tongue felt clamped to her mouth’s roof.

The being then turned aside and appeared to stumble away from her window. Amelia had the impression it was going around the house and wasn’t coming for her at all. Breaking out of the terror that had made her motionless, Amelia leapt from the bed, dashed to the door and fumbled the key into the lock. But then she heard a ‘scratch, scratch, scratch upon the window, and saw a hideous brown face with flaming eyes glaring in at her. She rushed back to the bed, but the creature continued to scratch, scratch, scratch’.

Somewhere in the panic of her mind, Amelia knew at least that the window was locked so the creature was unlikely to gain entry. The scratching did indeed stop, but now there came a pecking sound. An awful realisation flooded over Amelia – the beast was unpicking the lead that held the window in the frame. The peck, peck, pecking went on until the pane fell into the room, shattering into diamonds on the floor. Then ‘the long bony finger of the creature came in and turned the handle of the window, and the window opened.’

The creature clambered in and strode across Amelia’s room, but ‘her terror was so great that she could not scream … it came up to her bed, and it twisted its long, bony fingers into her hair, and it dragged her head over the side of the bed and – it bit her violently in the throat.’

As the fiend pierced Amelia’s flesh ‘her voice was released’. She let out a horrifying scream and her brothers were right at her door. Finding it locked, they searched for a poker to lever it open with, losing a vital minute as the creature bit deeper into their sister’s neck. With the fire iron, they got the door ajar and rushed into the room – just in time to see the creature escaping through the window. Their sister was unconscious, draped over the side of the bed, ‘bleeding violently from a wound in her throat’. One brother chased the vampire, but it scurried across the lawn ‘with gigantic strides’ and vanished over the churchyard wall.

Might the Vampire of Croglin Grange have taken a bite like this?

When Amelia had recovered consciousness and her shock had subsided a little, she said, ‘What has happened is most extraordinary and I am very much hurt. It seems inexplicable, but of course there is an explanation and we must wait for it.’

Amelia ‘was of strong disposition, not even given to romance or superstition’ and she soon came up with an idea to account for that night’s events. She said, ‘It will turn out that a lunatic has escaped from some asylum and found his way here.’

Amelia’s wound healed and she appeared to be getting over the trauma of her experience. Her doctor, however, insisted that – to fully recover – she must have a change of scene. Her brothers took her to Switzerland, where they undertook the typical pastimes of earnest Victorian tourists, such as climbing mountains, picking and preserving plants, and making sketches. As Autumn came on, however, Amelia agitated to go back to Croglin Grange.

‘We have taken it,’ she said, ‘for seven years, and we have only been there one; and we shall always find it difficult to let a house which is only one storey high, so we had better return there; lunatics do not escape every day.’

Amelia’s brothers were also missing their – vampire attacks excepted – pleasant life at Croglin so they agreed to her suggestion and the three headed back. As Croglin Grange, however, had only one storey it was difficult to make their living arrangements more secure. Amelia occupied her former bedroom, but always closed the shutters at night. As was typical for many old houses, though, the shutters left the top of the windowpane uncovered. The brothers now shared a room opposite Amelia’s and kept loaded pistols by their bedsides.

The siblings spent a happy and uneventful winter at the Grange though they did hear some disturbing reports of animals found dead with gashes in their throats. Then one spring night an ominously familiar noise woke Amelia up – a scratch, scratch, scratch at the window. She looked up and saw the same hideous shrivelled face she’d seen the previous summer, staring down at her from the top of the window with its blazing eyes. Amelia let out a huge scream, her brothers leapt from their beds and were soon charging out of the house’s front door clutching their pistols. The creature bolted across the lawn, scampering in its ungainly stride. One of the brothers fired and lodged a bullet in its leg. Though limping, the creature kept up its run, and again escaped by clambering over the churchyard wall. Although it was too dark to make out much, one brother – as he sprinted after the vampire – thought he saw it disappearing into the crypt of a long-extinguished family.

The following day, the brothers told Croglin Grange’s tenants about the ghastly episode of the night before. They assembled a band of men and went to investigate the vault. Breaking open the doors, they were confronted by the sight of shattered coffins and mangled human remains strewn across the ground. Just one casket was reasonably intact. Its lid – though not attached to the rest of the coffin – lay on top of it loosely. The brothers lifted it to reveal a withered, mummified creature similar to the one they’d chased. The vampire had a tell-tale pistol wound in its leg.

The brothers – or, more likely, their tenants – knew there was only one way a vampire could be quietened. They dragged the hideous corpse out of the crypt with the intention of burning it. Some say they pulled the vampire towards a holly tree in the churchyard, as holly was considered by the local folklore as beneficial in such an operation. There they incinerated the dreadful cadaver and all the outrages of the Croglin Vampire ceased. You can still see the holly tree’s stump in Croglin Churchyard.

Croglin Church, Cumbria, England – did the Croglin Vampire issue forth from a vault in its graveyard? (Photo courtesy of News & Star)

Might the Croglin Vampire Story Have Been Lifted from a Victorian Penny Dreadful?

The Croglin Vampire legend ensnared the imagination of the late-Victorian public and it remains known among vampire aficionados today, with some making the pilgrimage up to Croglin to mooch about the churchyard. Some even say the Croglin story inspired Dracula author Bram Stoker. As the tale, however, appeared in Augustus Hare’s second chunk of autobiography – which was only published in 1900 – and Dracula came out in 1897, this would seem unlikely, unless Stoker had heard the story some other way.

It wasn’t long, though, before the Croglin Vampire’s status as a creature of genuine folklore began to be challenged. One writer of note who expressed scepticism was Montague Summers (1880-1948). Summers was a highly eccentric character who posed as a Catholic priest, though there’s no firm evidence he was ever ordained. Obsessed with witchcraft, vampires and werewolves – all of which he claimed to literally believe in – Summers produced the first English translation of the notorious 15th-century witch hunters’ guide, the Malleus Maleficarum. Summers was known for waltzing around the reading room of the British Museum in a black cloak and buckled shoes, clasping a black portfolio with ‘vampires’ written upon it in large blood-red letters.

Despite his reputation for gullibility, Montague Summers queried Hare’s account of the Vampire of Croglin Grange.

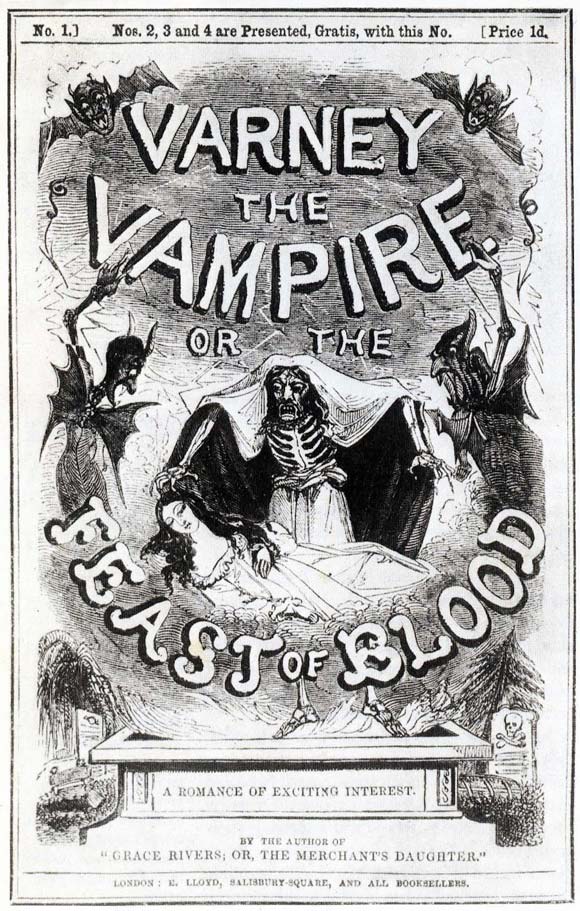

Although Summers didn’t dismiss the idea there might have been a vampire at Croglin, he felt much was questionable about Hare’s account. In his 1929 book The Vampire in Europe, Summers republished Hare’s story along with the first chapter of a work known as Varney the Vampire. This exercise was intended to reveal the similarities between the two texts, thereby suggesting Hare’s narrative had been heavily influenced by Varney.

Varney the Vampire; or, the Feast of Blood is an enormously long tale that was first published in a series of penny dreadfuls. (Cheap sensationalist stories that were printed in pamphlet form, put out in weekly instalments and aimed at working-class men.) The Varney the Vampire penny dreadfuls came out between 1845 and 1847 and in 1847 they were also cobbled together as a book. The writers – James Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest – were paid by the line, an arrangement which didn’t encourage brevity. As a complete book, Varney the Vampire comprises 876 double-columned pages, 232 chapters and almost 667,000 words. By comparison, the Bible weighs in at around 807,300.

Varney the Vampire – inspiration for the Vampire of Croglin Grange?

The story follows the adventures of the aristocratic vampire Sir Thomas Varney. Though Varney wasn’t the first publication to make the shambling, zombie-like vampire of Eastern European folklore into a suave aristocrat – that honour goes to John William Polidori’s novella The Vampyre (1819), whose antagonist is based on Lord Byron – Varney the Vampire did much to establish certain vampire tropes in the popular consciousness. It was the first story to refer to vampires as having sharpened teeth, containing the line: ‘With a plunge he seizes her neck in his fanglike teeth.’ (Though Polidori describes teeth marks in victims’ throats, he doesn’t claim fangs have inflicted them). Varney also turns a female character into a vampire and has incredible strength and hypnotic powers.

Vampiric bites aren’t the only similarity between Varney the Vampire and the Croglin Vampire story. We read of Varney ‘standing on the ledge immediately outside the long window. It is its finger nails upon the glass … the pattering and clattering of the nails continue … long nails, that appear as if the growth of many years had been untouched’. As well as sharing glass-tapping tendencies with the Croglin Vampire, Varney enters a woman’s room in a similar manner to his Cumbrian counterpart: ‘a small pane of glass is broken and the form from without introduces a long, gaunt hand, which seems utterly destitute of flesh. The fastening is removed.’ Like Amelia, the heroine in Varney ‘tries to scream … but a choking sensation comes over her and she cannot’ and she finds she ‘cannot withdraw her eyes from the fiend’. She is soon lying ‘half across the bed and half off it … her long hair streams across the entire width of the bed’. Varney then clasps ‘the long tresses of her hair’ and ‘twining them round his bony hands, he held her to the bed.’ As with the Vampire of Croglin Grange, Varney is chased off by the lady’s menfolk.

Varney the Vampire – like the Vampire of Croglin Grange – touches a woman’s hair with his bony fingers.

Varney the Vampire wasn’t considered worthy or respectable literature and probably wouldn’t have been the type of publication Captain Fisher or Augustus Hare would have admitted to possessing. Full of purple sentences – ‘She drew her breath short and thick. Her bosom heaves, her limbs tremble.’ – Varney also suffers from a convoluted plot. The setting pings between the 1730s, the mid-1900s and the Napoleonic Wars while Varney’s motivations lurch from the need to drink blood to an urge to extort money to a desire for revenge. At times Varney is depicted as a real vampire; at other times as a human who behaves like one. Despite the work’s shortcomings and the lower-class audience it was targeted at, Varney – like the tackier fringes of the horror genre today – may have been a guilty pleasure for some educated individuals. The parallels between Varney the Vampire and the Croglin Vampire tale do suggest that either Augustus Hare or Captain Fisher had a copy of this much-disparaged publication lurking in their home.

Rebuke, Ridicule and Resurrection – the Croglin Vampire Tale is Both Dismissed and Defended

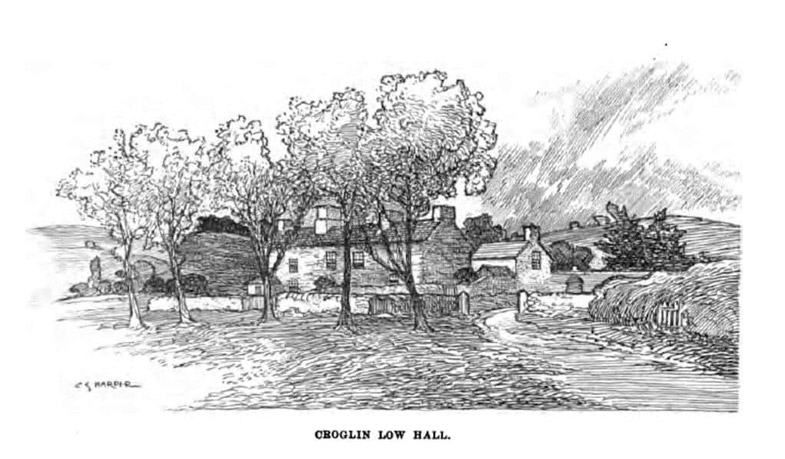

Even before Montague Summers started comparing vampire tales, another researcher – Charles G. Harper, an expert on haunted buildings – was snooping around in Cumbria. In his 1907 book Haunted Houses, Harper claimed he’d found no evidence Croglin Grange had even existed. He did stumble across two buildings – Croglin High Hall and Croglin Low Hall – but neither really matched Hare’s depiction of Croglin Grange. Croglin Low Hall came the closest, but it has two floors, a fact that would have probably obliged the vampire to shinny up the wall to get to Amelia’s window. Also, rather than having a spooky churchyard nestled in an adjacent hollow, Croglin Low Hall is around a mile from the nearest place of worship, St John the Baptist’s Church in the village of Croglin. And, though that church has a crypt underneath, there’s no vault in the churchyard dedicated to an extinct family nor any structure that even vaguely concurs with Hare’s description of the vampire’s mausoleum.

The next researcher to have a crack at the legend was Francis Clive-Ross. In a 1963 article for the journal Tomorrow, Clive-Ross stated he’d discovered information that might lend some truth at least to the setting of Fisher’s tale. Clive-Ross found out that Croglin Low Hall had actually been known as Croglin Grange until the beginning of the 18th century. The house had originally had only one storey and a second floor had been added later – Clive-Ross observed the corbels that would have once supported the roof. A chapel had also stood nearby, which Clive-Ross felt had been demolished around the time of the English Civil War (1642-51). He discovered the stubs of its walls and evidence of its foundations. (Historic England’s webpage about Croglin Low Hall also mentions the chapel, but states it was knocked down in the 19th century.) Clive-Ross found that the vampire story indeed seemed to be a long-standing legend in the Fisher-Rowe family. Croglin residents, however, told him that the incident hadn’t occurred in the 1870s, but rather way back in the 1680s.

Croglin Low Hall, Cumbria, England – site of the Croglin Vampire attack? This sketch must have been made after the building acquired its second storey.

In 1968, the American psychical researcher D. Scott Rogo had an article published in Fate magazine, which went into more detail about the similarities Montague Summers had noted between Hare’s account and Varney the Vampire. It was, however, a revelation in a book put out 10 years later that really added a new dimension to the Croglin Vampire conundrum. In his Haunted Churches and Abbeys of Britain, Marc Alexander stated he’d unearthed an account from a former Croglin rector, the Reverend Dr Matthew Roberts. Roberts linked a series of vampire attacks to sightings of a bat-like creature in Croglin Churchyard. Among the victims of this flying fiend was the daughter of one of Robert’s predecessors, the Reverend Joseph Ireland, who’d officiated at Croglin from 1804 to 1837. During the assault on Miss Ireland – as was the case with the Croglin Vampire – the creature was wounded and fled back to a tomb. The tomb it escaped to was that of the Reverend George Sanderson, who’d served at Croglin in the 17th century. Local rumour asserted the bat had appeared from Sanderson’s grave before other vampiric incidents.

The findings about the bat were later expanded on by the writer and researcher Geoff Holder. In Paranormal Cumbria (2012), Holder suggested the bat legend may be linked to the religious traumas of the mid-to-late-17th century. After the English Civil War, Parliament had imposed radical Puritan vicars on a lot of parishes, men who were often unwelcome and disliked. Then, after the Monarchy came back, the 1662 Act of Conformity dismissed many of these Puritan priests, replacing them with men loyal to the re-established Monarchy and the mainstream Church of England. This double upheaval caused anger, division and resentment in communities. George Sanderson had at first sided with Parliament, being one of the ‘intruding vicars’ it had imposed. At the Restoration, however, he abruptly switched sides and – as an orthodox Church of England priest – was forced on Croglin in 1671, after the sacking of its previous vicar. A turncoat such as Sanderson, who remained at Croglin until his death in 1691, may well have been less than popular. Holder suspects that, in the 1680s and 1690s, gossip about Sanderson grew more outlandish and – as the years passed – transformed itself into rumours of malevolent supernatural beings. These legends could have perhaps merged with tales about Croglin Low Hall and the demolished chapel that once stood next to it.

Also, as far as the Croglin Grange Vampire is concerned, Holder sees the 1950s as a ‘period of invention’ when a great deal of gothic baggage got added to Hare’s fairly sparse story. Hare’s narrative seems to have been combined with the vampire motifs widespread in fiction, film and the mass media at that time. During this decade, the young woman seems to have acquired the name Amelia, a suitable moniker for a gothic heroine. The brothers also appear to have got their names in this era, with one even referred to by the very un-nineteenth-century title of ‘Mike’.

In 2005, another twist was put on the Croglin Vampire saga by the crime historian Richard Wittington-Egan. Whittington-Egan discovered that Captain Fisher’s family were not the age-old owners of Croglin Grange as Hare had been led to believe. They were just tenants, who took on Croglin Low Hall’s lease in 1809. Whittington-Egan suspects the vampire legend was passed on to them, possibly by the Hall’s real owner – a man called Johnson – or by members of the Towry family. The Towries had owned Croglin Low Hall from the late 1680s to 1727 and some still lived nearby.

Fisher may have linked his family more firmly to both the Hall and its legend out of class consciousness. This might be seen in the fact that – while admitting to Hare that Fisher was a ‘very plebeian name’ – the Captain insisted his family was ‘of a very ancient lineage’. Finding himself at dinner with a well-known writer and other distinguished guests – who apparently included the Earl of Ravensworth – could Fisher have been tempted to invent an impressive ancestry, one that encompassed not only the generations-long ownership of a family seat but an aristocratic ghost story to go with it? In addition, it’s been suggested that the property the Fisher-Rowes moved to in Surrey, Thorncombe Park, also has resemblances to the Captain’s description of Croglin Grange.

This is all quite a jumble of information, spanning several centuries and involving varied characters each with their own motivations. Let’s try to untangle this heap of fact, rumour and legend in the next section and see if we can rearrange the threads and form some tentative conclusions about Croglin Grange’s vampire.

Revenants, Red-eyed Owls, Peckish Circus Monkeys and Blood-glugging Aristocrats – What Exactly Was the Vampire of Croglin Grange?

It’s my suspicion that the genesis of the Croglin Vampire story can be found in the traumas and upheavals of the English Civil War and the decades after it. I’d guess the story was then given – by Augustus Hare and Captain Fisher – a Victorian gothic gloss and was subjected to further gothic overlays in the mid-20th century.

We’ve already seen how the legend of the vampiric bat is linked to the tomb of the 17th-century vicar George Sanderson. I suspect the bat – as such creatures were staples of Victorian gothic horror – was an imposition on an earlier legend, especially as our clearest record of the creature has it attacking the maidenly daughter of a man who was the local vicar right before Queen Victoria came to the throne. But other things do point to Croglin’s vampire legends as having links to the mid-to-late 17th-century – the fact the house was then known as Croglin Grange and had just one storey and a chapel next to it; the period of George Sanderson’s reign as rector; the assertions of the villagers about when the legend took place; and the fact that period of history was a most traumatic time.

Supernatural occurrences and a fascination with the occult are often associated with eras of rapid change, disorientation and tragedy. As well as the death, maiming, sieges and general destruction caused by the English Civil War, the conflict also severely shook the mental worlds of many people. The King’s head was chopped off and a republic set up, both occurrences that would have been utterly unthinkable in the strictly hierarchical, semi-feudal society of just a few decades previously. Radical religious doctrines were preached and religious disputes grew more bitter. Political agitation also intensified and the roots of ideas like liberalism, socialism and democracy can be traced back to this tumultuous epoch, an epoch many termed ‘the world turned upside down’. In terms of economics, the emerging capitalist system was overturning old certainties, enriching some and impoverishing others, and straining social bonds. We might ask what all this has to do with vampires, but societal anxieties often manifest in rumours of such monsters. At the time of the Victorian vampire craze, for instance, society was undergoing rapid industrialisation and urbanisation and a realignment of gender roles.

People who know a little about bloodsuckers might be shocked to hear of a creature like the Vampire of Croglin Grange appearing in England. The folkloric vampire is much more associated with Central and Eastern Europe, the Balkans and Turkey. Unlike the later aristocratic vampire popularised by writers like John Polidori and Bram Stoker, this rustic creature was of peasant stock. In no way suave or sexually alluring, this being was a stinking corpse that couldn’t rest, usually because it had been murdered or improperly buried. The folkloric vampire would shuffle out of its tomb at night to feed on the blood of its relatives and ex-neighbours, thereby prolonging its miserably undead existence until a stake through the heart brought an end to its nocturnal wanderings.

Was Croglin’s vampire more of a folkloric nosferatu than a literary Victorian bloodsucker?

Though such creatures are uncommon in English folklore, there are occasional records of similar beings known as revenants. The term ‘revenant’ can simply refer to a ghost – the word derives from an Old French verb revenir, which means ‘to return’. A revenant, however, can also be a corpse that issues from its grave to cause mischief and – sometimes – to feed on the living. These entities mostly appear in England at times of turmoil.

Many revenant legends date from around the time of the Anarchy (1135-1153), a period of civil war in which law and order broke down and in which Stephen of Blois and the Empress Matilda contended for the English throne. William of Newbury (1136-1198) wrote that ‘it would not be easy to believe that the corpses of the dead should sally (I know not by what agency) from their graves, and should wander about to the terror or destruction of the living, and again return to the tomb, which of its own accord spontaneously opened to receive them, did not frequent examples, occurring in our own times, suffice to establish this fact, to the truth of which there is abundant testimony.’

William related the case of ‘a man of evil conduct’ who’d fled from York to a country village. The man died and was buried, but soon issued ‘by the handiwork of Satan, from his grave at night-time, and pursued by a pack of dogs with horrible barkings, he wandered through the courts and around the houses while all men made fast their doors, and didn’t dare to go abroad on any errand whatever from the beginning of the night till sunrise, for fear of meeting and being beaten black and blue by this vagrant monster.’

The revenant, however, managed to kill some people – and the way the locals dealt with it is interesting. ‘Hastening to the cemetery’ they began to dig and it wasn’t long until they had ‘laid bare the corpse, swollen to an enormous corpulence, with its countenance beyond measure turgid and suffused with blood.’ Some young men ‘inflicted a wound on the senseless carcass, out of which incontinently flowed such a stream of blood that it might have been taken for a leech filled with the blood of many persons. Then, dragging it beyond the village, they speedily constructed a funeral pile, and upon one of them saying that the pestilential body would not burn unless its heart were torn out, the other laid open its side by repeated blows of the blunted spade, and, thrusting in his hand, dragged out the accursed heart. This being torn piecemeal’ the body was ‘now consigned to the flames’.

Another 12th-century writer, the Welshman Walter Map, wrote of a ‘wicked man’ in Herefordshire who rose up from the dead and got into the habit of wandering through his village at night, shouting out the names of those who’d die of sickness within the next three days. A bishop advised the locals to ‘dig up the body and cut off the head with a spade, sprinkle it with holy water and re-inter it.’

So we can see that English revenants do have at least some similarities to Eastern European vampires. The Vampire of Croglin Grange to me seems more like a revenant than a Byronic, aristocratic bloodsucker from Georgian or Victorian literature. It has the appearance of a hideous corpse and it shambles from its tomb at night to cause mayhem and feed. Like William of Newbury’s revenant, it is dealt with by being burnt. If Croglin’s vampire does date from the time of the Civil War, might it be an example of societal stresses being expressed through fears of the supernatural, as happened in the earlier upheavals of the Anarchy? The only aristocratic aspect of the Croglin Vampire is the fact it retreated into the tomb of an extinct – though presumably well-to-do – family. Unlike in some Victorian vampire chronicles, there’s no suggestion of Amelia herself being turned into a vampire. Another folkloric feature of the Croglin beast is its blazing eyes, something British legend ascribes to a number of supernatural creatures, such as phantom black dogs.

The Croglin Grange tale has similarities to another Cumbrian legend involving a revenant-like being. In the village of Dent in 1715, a man died at the suspiciously advanced age of 94. Despite having a decent Christian burial, he was soon seen roaming around the village and was suspected of feasting on animals’ blood. A farmer one day saw a black hare, shot it and followed the injured animal as it fled. The hare disappeared into the revenant’s old house. The farmer looked through the window and saw the man bandaging a gunshot wound. (It’s common in folklore for evil beings to be identified by the wounds inflicted on them.) This revenant’s – or vampire’s – activities ceased when the corpse was reinterred in a new grave and a metal pole was pounded through its heart.

But what about the Victorian elements in the Croglin Vampire case? There are the influences from Varney the Vampire and the fact that the rather passive but sensible and resourceful Amelia shares traits with the heroines of writers like Charles Dickens and Bram Stoker. I suspect that either Augustus Hare or Captain Fisher or both of them couldn’t help mixing some of the gothic themes popular in Victorian fiction into an old legend. Hare had his book to sell and Fisher may have updated the story to lend a more aristocratic aura to his family tree.

Other explanations have been put forward for the Vampire of Croglin Grange: the young woman later known as Amelia might have spotted the eyes of an owl hovering over the lawn or flitting around the trees and – hypnotised by the moonlit night – let her imagination carry her off. A more outlandish suggestion is that an escaped circus monkey – who found himself starving and lost in Cumbria’s bleak terrain – launched the attack. But – unless I find out more about this curious story – I suspect the most likely scenario is that a legend stemming from Civil War trauma was later augmented with Victorian gothic outpourings.

Croglin Low Hall, with the window the vampire apparently came through bricked up and protected by lucky horseshoes. (Photo courtesy of Darren W. Ritson from The Spooky Isles)

Vampire commotions have occurred in modern times, as if the powerful archetype of the bloodsucker refuses to be laid to rest. In the 1950s, a vampire was rumoured to prowl Glasgow’s Southern Necropolis while the 1970s saw an outbreak of vampire hysteria focused on London’s Highgate Cemetery. But what of the Vampire of Croglin Grange? Does anyone still believe in or care about the legend, except for the occasional vampire obsessives who straggle into Croglin village? Lionel and Patricia Fanthorp’s 1997 book The World’s Greatest Unsolved Mysteries contains a photo of Croglin Low Hall, showing the window through which the vampire is alleged to have entered. A more recent photograph – exhibited in 2019 in a presentation given by Deborah Hyde, editor of The Skeptic Magazine – shows the same window. The window has been bricked up and is festooned with lucky horseshoes. Someone, it seems, doesn’t want to take chances.

(This article’s main image is from the 1922 German Expressionist vampire film Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror.)

What a fascinating account. I knew the story, vaguely, but you tell it so enthrallingly, and all the research into its origins makes for compelling reading. Thank you.

Thanks, George, the Croglin Vampire tale is certainly a fascinating and complex legend, weaving the Victorian gothic with something older and darker. Glad you enjoyed the article.

do the current owners have a realistic explanation for the bricked up window?

To be honest, I don’t know.

Hi David. I’m a born and bred Cumbrian living in Carlisle. I’ve followed this story for many years and i believe that there is a lot of truth in it. Your account and research is one of the best i have read.

Croglin (especially at night) can be a very eerie place!

Best regards, Ian Reading

Many thanks, Ian. I’m sure Croglin can be eerie!

Great article! I remember reading that story by Hare when I was 12. Loved it.

Many thanks, Lawrence. Hare’s story’s a wonderful piece of Victorian gothic!

Hi David, I lived in Kirkoswald until I was 9 years old. I’d read about the Croglin vampire in a Hamlyn book of horror when I was 7 years old. As I knew Croglin was only a couple of miles away I spent many nights completely terrified it would visit me whilst I slept.

Very interesting and well-researched. Have you read this: file:///C:/Users/mwalk/Downloads/Craig+Augustin+Calmet+and+Vampires.pdf

As a amateur YA fantasy writer and having just moved here 2 yrs ago my bf told me of this legend must say it is very intriguing according to him he has a connection on his mother side he won’t go into details as child he went to investigate said places and says something happened and him he will never go back even though I was drawn to go and see for myself he won’t so must be something in all this needless to say I will not press him on such things and have resigned to the fact he’s not willing to go then best probably not to he’s not one to back away from things .

The Bowman family lived in Croglin Low Hall until about the 1930s or so.

The new owners had a fire I think in a chimney and the ‘fire brigade’ had to remove the fireplace and destroy the wall. Found behind the wall was a room, a bed and the skeleton of a young woman.

I believe/know this because one of the Bowman family married into my family in the 30s.

Does anyone else know of this story?

Liz Lawson

As a child my family and I lived in Cross House, Ainstable.

Wow, that adds a whole new dimension to the story! Thanks very much for your comment, Liz.

Greetings

I am a delivery driver providing service to YODEL, and it happens that Croglin is one of the places that I visit everyday.

I heard about this today by a fellow driver, so I’ve searched for information about it and found your excellent work, again, excellent work, well done.

I do have a great interest in folklore, legends and history, do a lot of reading and research.

Tomorrow I will ask a few questions to my Croglin customers, who knows I may find anything interesting, and if allow, I will share it with you, for I bet you have a lot of data about it.

Well done

Good night

José

Cheers, Jose, I look forward to hearing anything you find out about the Croglin Vampire!

I grew up in Lazonby and my grandparents lived in Kirkoswald. As a youth my father did some work on local farms including at Croglin Low Hall. My father recounted that the driveway leading up to the farm had some old gravestones as part of the walls; these had apparently been repurposed from the local churchyard at some time past.

When I was living at home in my late teens circa 1992, a neighbour used to do some housework for my mother. This lady, Anne, told me she had experienced hauntings while working at Croglin Low Hall in the past in the form of whispering voices and shadowy figures.

May as well add this while I’m on. On another occasion, Anne also told me that the previous evening she had been returning in the car with her family from an evening meal at the pub in the village of Cumwhitton. On the edge of the village through the car window she saw a figure standing on a small hill who she described as looking like “a soldier” with a sword and helmet. She pointed him out to her family but they couldn’t see anything, and joked that Anne must be drunk.

A couple of years later, Anne, who had a number of health issues, passed away.

In 2004 (a number of years after Anne’s death) metal detectorists found a Viking burial of six bodies, jewellery and swords in the same location just outside Cumwhitton where Anne had seen the figure in the moonlight.

Thanks so much for your comment Mark – fascinating stories. Croglin does seem like a thoroughly spooky place!