One of England’s most famous legends concerns the Tower of London and certain black-feathered inhabitants of that ancient fortress. The legend says that if the Tower’s resident flock of ravens were ever to desert the stronghold, the building would disintegrate into dust. Not only that, but the ominous departure of these mystical birds would herald the collapse of England’s monarchy and even the destruction of England itself.

But how far back does this peculiar legend go? Is it genuinely ancient or much more recent than we might think? And what folklore – associated both with the area around the Tower of London and with the playful, cunning and intelligent raven – might have woven itself into this strange story?

Let’s first take a look at the legend of the ravens and the Tower of London as it’s commonly understood before exploring what folkloric, mythic and historical resonances might have become caught up in it. We’ll then investigate just how much this wonderfully gothic tale holds up under the light of a more clinical scrutiny.

Prepare yourself for accounts of infuriated royal stargazers, eccentric Welsh bards, severed yet talkative heads, and ravens being given ranks in Britain’s armed forces. You’ll also read about Tower ravens deciding to relocate to pubs, sorcerers sending their souls outside their bodies, decapitated queens, London’s three sacred mounds, Victorian gothic resculptings of England’s bloody history, and how the Tower of London’s precious ravens have been threatened by the Covid-19 lockdown.

The Tower of London and Its Ravens – a History of Legend, or a Legendary History

Many believe that ravens have lived on the site of the Tower of London since at least Roman times, congregating in the Roman fortifications that preceded England’s famous stronghold. In his Biography of London, Peter Ackroyd suggests that semi-domesticated ravens would have been a common sight around the Roman city of Londinium, with the birds helping keep the streets clean by scavenging scraps and bits of offal.

After the Romans left and the medieval epoch began, it appears that Londoners still appreciated ravens – as well as kites – for the same reason. Laws prescribed the death penalty for killing these birds and some ravens were apparently so tame they’d eat bread from children’s hands. One traveller remarked on the city’s ‘quite tame’ kites and it seems that butchers threw out their leftovers for ravens and kites to gobble.

Following the Norman Conquest of 1066, William the Conqueror – keen to assert his authority over a potentially rebellious London – built a wooden stockade where the Tower of London now stands. After a fire in 1077, which destroyed much of the wooden city, the Normans began to build the White Tower, a stone fortification that’s still the centrepiece of the Tower of London today. As the years passed, various monarchs added to the stronghold and a moat was dug so the dark waters of the Thames could encircle it. In the Middle Ages, there’s no reason to suspect that London’s ubiquitous ravens wouldn’t have frequented the expanding fortress. Eastcheap Market – famous for its butchers – was nearby so it’s likely some ravens that congregated there made the short hop and wing-flap to the Tower.

The White Tower, the first stone building constructed at the Tower of London and still its centrepiece

Legend claims that a particularly gruesome function of the Tower may have attracted them. For centuries, the Tower of London held prisoners – mostly royal or aristocratic – accused of treason. The lives of these inmates sometimes came to an end beneath the executioner’s sword or axe, occasionally on Tower Green – inside the Tower’s Walls – but more commonly on Tower Hill, just outside them. Ravens, due to their scavenging habits, have long been associated with gallows, gibbets and places of execution.

The birds were said to pluck out the eyes of the newly decapitated. They may have also scavenged blood and scraps of flesh. English executioners were not known for their competence. As there weren’t that many royal or noble-born traitors to behead (commoners convicted of treason were hung, drawn and quartered), executioners were usually out of practice. They also seem to have often been drunk. The messy, drawn-out hacking or slashing, then, might have allowed nimble ravens to swoop in for a snack. A visitor to London records children ‘gathering up the blood which had fallen through the slits in the scaffold’ following a beheading on Tower Hill. If children could do this, then why not the city’s ravens?

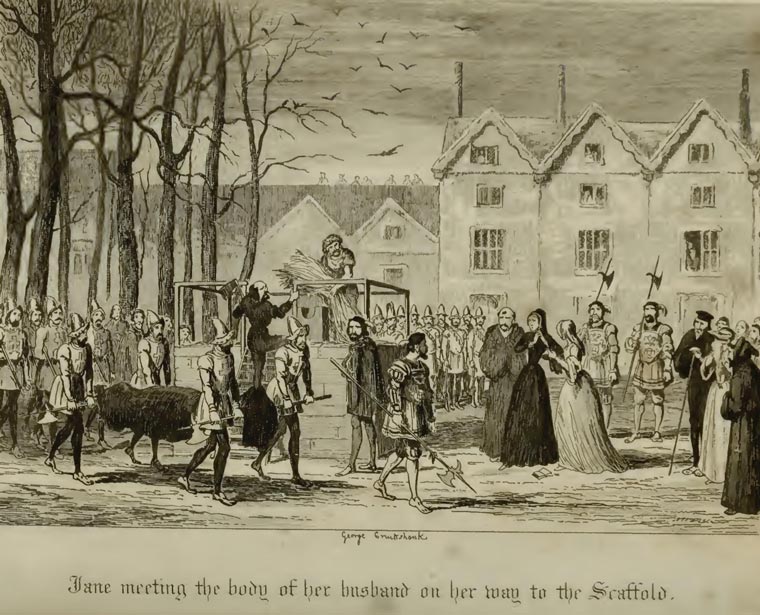

The ravens, though, sometimes had a sense of decorum. When Henry VIII executed his second queen Anne Boleyn in 1536, he – perhaps out of some lingering affection for her – had her beheaded on the private Tower Green rather than the public Tower Hill, where convicts knelt before jeering crowds. Henry also brought over a skilled French swordsman – to mercifully allow his ex a swift clean passage from this life. The ravens, sensing the solemnity of the event, apparently ‘sat silent and immovable on the battlements and gazed eerily at the strange scene. A queen about to die!’ The birds weren’t, though, it’s said, so considerate when Lady Jane Grey – a young noblewoman who reigned for a farcical nine days before being deposed in favour of Mary I – was executed in February 1554. Though Jane also had the privilege of being beheaded on Tower Green, the ravens soon flew in to peck her eyes out.

The first reference, however, to the legend that the kingdom will fall if the ravens leave the Tower of London concerns the reign of Charles II (1660-85). Charles’s royal astronomer, John Flamsteed, had an observatory in the White Tower. Flamsteed complained about the Tower’s ravens – of which there were apparently hundreds – flying past his telescopes and obscuring the sky. Some versions of the legend say Charles himself was fed up with the birds’ droppings besmirching his optical instruments.

Charles commanded that the ravens should be destroyed, but one of his courtiers reminded him of the legend that the ravens leaving the Tower would mean the monarchy’s collapse. Perhaps thinking of his father’s fate – who’d lost his kingdom and his head not long ago – Charles ordered that the ravens should be protected forever, with at least six kept at the Tower at all times. As for Flamsteed, he and his observatory were shunted out to Greenwich, where there’s still an observatory to this day.

A different take on the legend says that – after the Great Fire of London in 1666 – citizens started persecuting ravens for scavenging. Flamsteed explained to Charles that the death of the last raven would result in England’s fall, so Charles ordered that six should be kept safely in the Tower of London.

Much folklore is woven around the Tower of London’s ravens. (Photo: The History Girls)

Thereafter, folklore asserts, all England’s monarchs made sure there were at least six ravens in the fortress. This custom perhaps acquired more urgency when London’s wild raven population began to decline. No longer revered as vital cleaners of the streets, from around the turn of the 19th century ravens were accused of preying on livestock and hunted down. Their numbers plummeted in the capital and the surrounding countryside. The last pair of wild ravens in London were recorded nesting in Hyde Park in 1826. Wild ravens are still extinct in the capital. Gulls, which don’t seem to have appeared in London until around 1890, eventually replaced them as the city’s airborne scavengers.

The Tower ravens, however, found a new purpose as the Tower of London morphed from a place of imprisonment and execution into more of a tourist attraction. The ravens helped create a suitably macabre backdrop to the gothic tales of executions and medieval skullduggery the Victorians delighted in. As Britain moved into the 20th century and Victorian restraint eroded, the tales of beheadings got more gruesome and the ravens found themselves increasingly popular, appearing in a range of artworks and books.

England under Threat – The Tower of London and Its Ravens Struggle with World War II, Escapes, Kidnappings and Covid-19

World War II wasn’t a good time for the Tower of London’s ravens. The Tower closed to the public and the moat – long-drained over health fears – was turned into a vegetable garden to help the war effort. The fortress even resumed its former role as a jail, holding German spies and prisoners of war, with one man being executed there. The ravens, deprived of the food handouts and amusement the tourists brought, were – though – put to use as unofficial spotters of enemy planes and bombs. Those bombs, however, killed several ravens while others fled the Tower or died of shock during air-raids. Legend says Winston Churchill – a Freemason fascinated by the occult – was superstitious enough to boost the ravens’ numbers. When the Tower of London reopened to visitors on New Year’s Day 1946, a full contingent of ravens was waiting to welcome them.

The ravens at the Tower have since been extremely well-treated. They’re housed in a luxurious aviary close to the Bloody Tower and the sole task of one of the Beefeaters, the Ravenmaster, is to look after them. The ravens are well-fed – in addition to treats from visitors, they get through a tonne of meat a year. Sheep’s hearts and biscuits dipped in blood are particularly popular snacks. The Tower ravens – due to their pampered lifestyles – enjoy exceptional longevity. The longest-lived on record made it to 44. When they do expire, the ravens are laid to rest in a special graveyard, in the Tower of London’s South Moat. Recently, seven or eight ravens have been kept at the Tower – the ‘traditional’ six with one or two spares.

At the Tower of London, the sole task of one of the Beefeaters – the Ravenmaster – is to look after the fortress’s ravens. (Photo: Leighton Buzzard Observer)

The clan of ravens has, however, sometimes seen its numbers depleted, potentially placing the monarchy and kingdom under threat. The strength of superstition can be seen in the fact any ravens lost are swiftly substituted. Some ravens have been dismissed in disgrace. Since the War, the Tower of London’s ravens have been official members of the British armed forces, even being awarded ranks. This means that – like soldiers, sailors or air force personnel– they can be sacked for misbehaviour. Raven George was retired to Wales after amusing himself by damaging car aerials. A decree was issued, which curtly stated: ‘On Saturday, 13th September 1986, Raven George, enlisted 1975, was posted to the Welsh Mountain Zoo. Conduct unsatisfactory, service therefore no longer required.’

Another raven is thought to have been kidnapped shortly after World War II, a mystery that has never been fully explained. In May 2013, a fox sneaked into the Tower and killed two ravens while another bird – Charlie – bit a bomb-sniffing dog and died after the dog grabbed him. The Tower ravens have the feathers on one of their wings clipped, meaning they can fly but not far. This hasn’t prevented some escaping. The – appropriately named – Grog fled the Tower for an East End pub and another bird, Muninn, went missing for three days. She got across the Thames, but was captured in a back garden in Greenwich and brought back to the Tower.

The latest challenge to the Tower and its ravens is the Covid-19 pandemic, a situation that has sparked a number of humorously concerned articles in the British press. After the Tower closed to visitors, the ravens missed both the fun they had with the tourists and the tidbits the tourists feed them (though visitors aren’t officially meant to feed the birds). Ravens – mischievous and intelligent – need constant amusement. Those at the Tower have been known to delight themselves by stealing sandwiches out of people’s hands and tricking them by ‘playing dead’. One bird – called Edgar Sopper – did this so convincingly that the Ravenmaster really thought he had died. He sorrowfully picked up the ‘corpse’ only to have the raven bite him and flap off ‘croaking huge raven laughs’. With the dearth of visitors due to the coronavirus, the ravens have been given footballs, squeaky toys and teddies to keep them entertained. But the lack of amusement and food – ravens have been knocking on the Beefeaters’ windows begging for scraps – have already led to some escape attempts, with the birds Merlina and Jubilee being the worst offenders.

The Tower of London – this massive fortress covers 12 acres and hosted nearly 2.86 million visitors in 2018. (Photo: Duncan)

But what strands of folklore might be wrapped up in the – apparently powerful and enduring – legend of the Tower of London and its ravens? Let’s examine the archetypes and anxieties that might lurk behind this myth before querying the antiquity of the legend itself.

What Strands of Folklore Might Be Entangled in the Tales of the Tower and Its Ravens?

Bran the Blessed, Bran’s Talkative Severed Head and the ‘Sacred Psychogeography’ of Tower Hill

The Welsh medieval collection of tales The Mabinogion – written in the 12th and 13th centuries but drawing on much older oral traditions – includes a character called Bran the Blessed. Bran – a giant and king of the island of Britain – appears in the story Branwen, daughter of Llyr. In this account, Branwen – Bran’s sister – marries the Irish king, but is treated badly, leading to a battle on Irish soil between the king’s followers and Bran’s.

After the battle, Bran – fatally wounded in the foot – asks his followers to ‘cut off my head and take it to London. Eventually, you must bury it in state on the White Hill of London, turning my head towards France.’

Bran’s head is, therefore, ceremonially lopped off. His followers return with it to Britain and spend many years in strange wanderings, during which the head – still able to speak – proves an entertaining companion. Bran’s entourage finally reach London and the head is interred as Bran has requested, with the understanding that it’s faced towards France to repel invasions from the Continent. Interestingly, the White Hill is thought to be the mound known as Tower Hill today and the Welsh name ‘Bran’ translates into English as ‘crow or raven’.

There are aspects of Bran’s legend that relate to the functions of the Tower of London and the later folklore that would surround it. Bran is a king and the Tower – as well as being a prison – was also long used as a royal palace. When William the Conqueror began to build the Tower, its purpose wasn’t only to overawe the unruly City of London, but to guard the vital thoroughfare of the Thames, up which invaders – such as Vikings – had come. Even as late as World War II, the Tower was garrisoned with soldiers and was one of the fortifications designated to protect London in the event of a German land assault.

Bran’s myth is undoubtedly linked with the Celtic cult of the head. The Celts believed that the head contained the soul as well as the intellect, and the heads of enemies were prized as powerful magical instruments. It’s interesting that Bran’s head was buried in a place where 125 heads are estimated to have rolled over the centuries.

Tower Hill is associated with other ancient kings. King Brutus – the mythical founder of Britain and London – is said to be buried there. Some legends claim King Arthur – somewhat arrogantly – dug up Bran’s head from Tower Hill, stating that he would be the one who’d keep Britain safe from Saxon invasion. Perhaps the eventual loss of England to the Saxons was the result of this rashness.

The site of the scaffold on Tower Hill, outside the Tower of London’s walls. Around 125 heads rolled here while only seven people were beheaded on the more famous Tower Green. (Photo: Bryan MacKinnon)

It’s difficult to know whether the legend of Bran had any influence on the later legend of the Tower of London’s ravens, but it’s intriguing that both myths have links to kingship, ravens and the security of the realm. Tower Hill has also been seen as a significant protrusion by antiquarians and modern psychogeographers. It’s apparently one of ‘London’s three sacred mounds’, the other two being Tothill, near Westminster Abbey, and Penton Hill, near Islington. All three hills boast – or are close to – healing springs and excavations on Tower Hill have also revealed traces of a medieval well and Iron-Age burial. Perhaps Tower Hill has been a strange centre of mythic energy for some time.

The Tower of London, the Ravens and the External Soul

A concept that might shed light on the mystery of the Tower of London and its ravens is the notion of the ‘external soul’. The idea is that a person can hide their ‘soul’ or ‘life’ in some external object, often an animal or plant. As long as the soul remains concealed and the plant or animal stays well, the person is invulnerable, but if the plant or animal is harmed or destroyed, the person will suffer injury or death. This idea was popularised by James George Frazer in his massive study of folklore, myth and religion The Golden Bough (1890) and – though Frazer is out-of-fashion today – his musings on the external soul might go some way to helping us understand the strange beliefs centred on the Tower’s ravens.

Folktales from many parts of the world feature a wicked character – often a giant, ogre or warlock – who has hidden his soul far away. This evildoer has usually kidnapped a princess and a hero must locate the external soul in order to kill her captor and free her. In a Norse story, a giant has hidden his soul in a well, in a church, on a distant island. In the well is a duck, in the duck is an egg and in the egg is the giant’s soul. The story’s hero manages to find the egg, he squeezes it and the giant bursts.

In some cultures, when a baby is born, their life is said to be bound up with a particular tree. If the tree grows strong and healthy, so will the young person, but if it withers and dies, the person will get sick and die too. Close to Dalhousie Castle, near Edinburgh, there grew an oak said to be intimately connected with the fortunes of the fortress’s owners. If a branch fell off the tree, it was thought a family member would soon die. In some tribal societies, people might believe that the lives of the members of a particular clan or the men or women of the tribe are bound up with those of a certain kind of animal: elephants, perhaps, or tortoises or monkeys. They will, therefore, avoid killing all members of that species as they cannot know which individual elephant or tortoise has their life linked with a certain individual of their clan.

With the ravens of the Tower, it’s slightly different as it’s thought the fate of the whole nation is connected with their welfare rather than just the lives of particular individuals. But might some shadowy notion of the external soul be seen in our somewhat ‘totemic’ attitudes towards the ravens?

Folklore Links the Raven with Death, Executions, Prophecy and Kingship

The common raven is found across Europe, North America, North Africa and northern and central Asia. In many parts of the planet, the raven’s intelligence, playfulness and striking black plumage have seen it gather similar associations in the local folklore. Much of this folklore ascribes characteristics to the raven that are also reflected in the Tower of London legend.

The legend foretells England’s (possible) doom and ravens are seen as sombre birds of prophecy. In Wales, it’s said that a raven cawing from a steeple overlooking a house means one of its occupants will soon die while a Scottish legend states that if a young child drinks from a raven’s skull, they’ll gain the gift of foresight. In Greek myth, ravens are linked to Apollo, the god of prophecy, and are the god’s messengers on earth. A Viking tradition claimed that if a warband’s banner – emblazoned with a raven – fluttered they’d be victorious in battle while if the banner drooped, they’d lose. The raven’s connection with prophecy probably comes from the bird’s unnerving ability to imitate human speech, leading to ravens being seen as ‘oracles’. Many visitors to the Tower of London have been surprised by a croaked ‘hello’ from a raven.

Since the late 1800s, the Tower of London’s ravens have been a tourist attraction. (Photo: Laura LaRose)

Ravens, like the Tower legend, are linked to kingship. A Cornish tradition claims that King Arthur turned into a raven after death and killing a raven was apparently for a long time a taboo act in that county. The legend of the German king Frederick Barbarossa – who shares some characteristics with Arthur – states that the monarch isn’t dead, but rather sleeping surrounded by his knights in a mountain cave. Ravens fly around the mountain and – when they cease to do so – he’ll wake up.

Though they’re not explicitly part of the Tower of London’s raven legend, the Tower has a strong association with executions and death. These themes are also found in the folklore of the raven, probably due to the birds’ deep black plumage, their ‘death-rattle-like’ croak and their habit of scavenging. Ravens are notorious for haunting gallows, scaffolds and gibbets. The executioner’s block is sometimes called a ‘ravenstone’ while in Germany ‘ravenstones’ can refer both to gravestones and ravens’ droppings after they’ve feasted on the corpses of criminals. In Celtic mythology, the warlike goddess Morrigan can take the form of a raven while hovering over scenes of slaughter and some Siberian peoples see ravens as spirits of war and violence. In Serbian legends, ravens often announce the deaths of heroes.

These are just some of the examples of the rich folklore of the raven that can be found across the world. Perhaps some of these associations contributed to the mythology of the ravens in the Tower.

But Wait a Minute – Might the Legend of the Ravens and the Tower of London Just Be a Victorian Invention?

Two ravens perch in front of the White Tower, at the Tower of London. (Photo: Jack’s Adventures in Museum Land)

Until quite recent times, it was accepted that the myth of the ravens at the Tower was of ancient pedigree, so accepted in fact that no one had actually researched how far back it went. But in the last couple of decades, this assumption has been challenged by two scholars: Boria Sax and Geoff Parnell, who’s an official Tower of London historian and member of the Royal Armouries staff. Sax and Parnell have concluded that there are no records of ravens at the Tower before the Victorian age.

This is especially curious as the Tower of London was long associated with all kinds of animals. Among its many functions, the Tower was London’s zoo, housing an impressive array of beasts, most of which had been given to the Royal Family by foreign monarchs. The Tower menagerie lasted from the late 1100s to 1835, when the remaining animals were transferred to the new London Zoo in Regent’s Park. The Tower’s zoo held – at various times – Barbary lions, leopards, wildcats, lynx, jackals, hyenas, brown and grizzly bears, eagles, monkeys, wolves, owls and a tiger. One famous resident was a polar bear, who was taken each day to fish for his lunch in the Thames. An African elephant, captured as a trophy during the Crusades, was given gallons of red wine by his keepers, who thought it would keep out the cold. The elephant didn’t live long. By the 18th century, the Tower zoo had become a popular visitor attraction – admission cost three half-pence though you got in free if you brought along a dog or cat to feed to the animals.

By 1828, the zoo boasted 280 animals from at least 60 species. There is, though, one striking omission from all the records, inventories and reports of the zoo’s creatures. There’s not one mention of ravens. This might be understandable for the centuries during which ravens were widespread in London, but there’s also no mention of the birds being kept at the Tower when London’s wild ravens were dying out.

The earliest reference to ravens in connection with the fortress is in the 1840 novel The Tower of London: A Historical Romance by William Harrison Ainsworth. This melodramatic book – which would do much to establish the image of the Tower in the Victorian mind as a gruesome torture chamber – mentions a flock of ravens and crows wheeling around during the execution of Lady Jane Grey. It seems, however, that Ainsworth just brought in these birds to give his beheading scene a suitably sinister backdrop – there’s no suggestion of such creatures actually living in the Tower.

An illustration in William Harrison Ainsworth’s gothic novel The Tower of London (1840) shows ravens wheeling in the sky, but not actually inside the Tower.

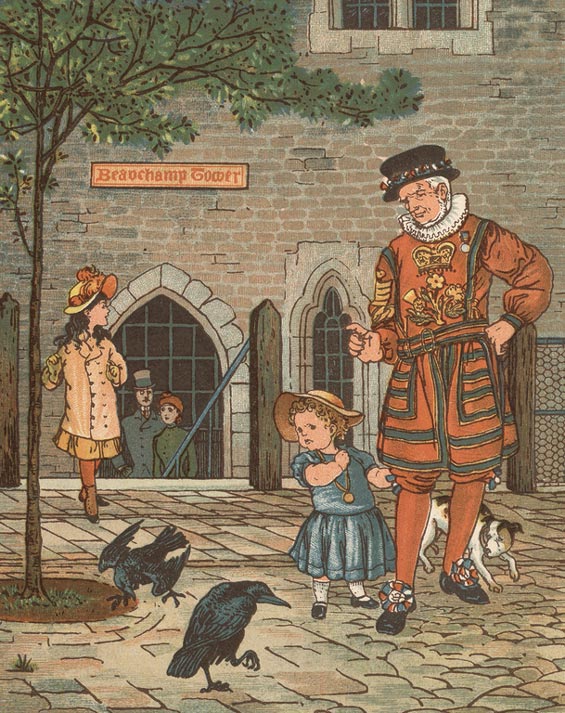

The first two sources to depict ravens within the Tower itself date from 1883. An illustration in the newspaper The Pictorial World includes a raven, though the bird is not of central importance in the picture. The raven is near Tower Green so the bird is probably being used as a gothic prop to emphasise the Green’s association with executions. The other 1883 source – a picture in the children’s book London Town – shows what we might nowadays consider a typical Tower of London scene. There’s a Beefeater and two haughty-looking ravens – a girl and dog are sheltering anxiously from the birds behind the Beefeater’s legs.

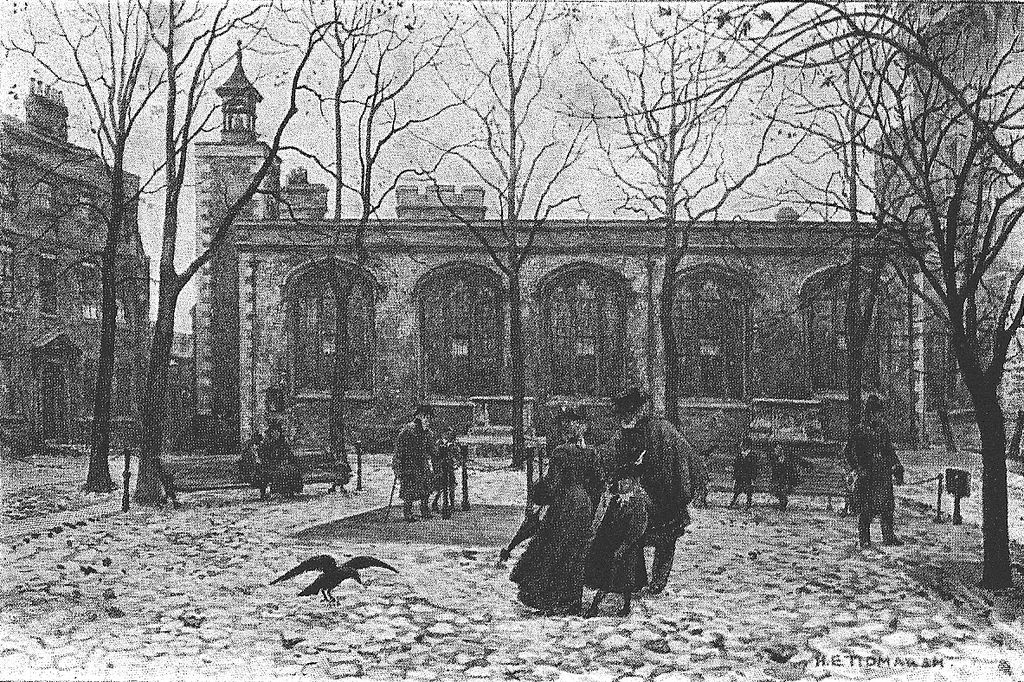

A picture from 1895 shows two ravens in the Tower of London, who are – with typical ravenlike mischievousness – tormenting a cat by pulling its tail. The picture appeared in the RSPCA (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals) journal The Animal World accompanied by a short article. We learn that one of the ravens is named Jenny. A painting by H.E. Tidmarsh – entitled Place of Execution in Front of St Peter’s Chapel – shows a raven landing ominously near a family of sightseers. This painting was published on a postcard in 1900 and later appeared in Cassell’s Magazine in June 1904. A 1904 picture by S.T. Dadd – called Ravens at the Tower – shows a Beefeater and some tourists with two ravens near the ‘site’ of Tower Green’s scaffold.

One of the two earliest-known depictions of ravens in the Tower of London, from the children’s book London Town (1883).

These sources indicate that in the late 1800s ravens became a feature of the Tower, often being associated with its history of beheadings. Boria Sax suggests that the ravens were – due to their strong cultural links with executions – employed to boost the Tower’s status as a tourist attraction, hence their appearing near Tower Green in visual materials. Public interest in the Tower’s decapitations seems to have been sparked by the fact that – on a visit to the stronghold – Prince Albert had remarked that Queen Victoria would like to see the spot where Anne Boleyn was executed. By 1866, a spot had been identified, a spot soon dramatised by the dubious claim that a permanent scaffold had stood at that location. The spot was surrounded by railings and marked with a plaque, and tourists presumably felt no visit to the Tower was complete without pausing there. Over the years, Sax argues, the ravens were increasingly required to act as gothic ornaments to this site of doom, which encouraged the Tower to maintain a flock.

The supposed site of the scaffold on Tower Green, close to St Peter’s Chapel – notice the raven perch in the background. (Photo: Chris Nyborg)

This would indeed fit with the Victorian view of the Tower – the Victorians were determined to reinvent the fortress as a medieval gothic Disneyland. Children were encouraged to pose with their heads on the executioner’s block. The stronghold’s post-medieval buildings were cleared away and the dilapidated Lanthorn Tower – despite originating in the Middle Ages – was deemed not medieval-looking enough. This problem was remedied by ‘renovations’, including the addition of gargoyles and grotesques. It’s not surprising that the ravens fitted into this world, but we might ask where the Tower’s ravens came from. Wild ravens – that could have been captured and tamed – would have by this time no longer flitted into the fortress.

Parnell suspects ravens may have been introduced to the Tower thanks to the popularity of Edgar Allan Poe’s poem The Raven (1845). This poem – featuring a young man grieving for a dead lover who’s surprised at midnight by a raven tapping on his window – started a craze for keeping the birds as pets. The Tower’s Beefeaters and other staff, Parnell argues, might have succumbed to this fashion. Their birds could have then morphed from private pets into an official flock.

An alternative suggestion is that the Tower’s ravens were supplied by the appropriately named Dunraven family. According to The Tower from Within by George Younghusband (1918), the Fourth Earl of Dunraven (1841-1926) provided the birds, perhaps in the hope of demonstrating some sort of spiritual connection between his lineage and the Tower. The Second Earl had been a patron of the eccentric Welsh bard Iolo Morganwg, who seems to have persuaded the family that their castle in Glamorgan had been the seat of King Bran, who wasn’t only a monarch and giant but also a raven god. Morganwg was a colourful individual, who styled himself as a ‘druid scholar’. A stone mason, poet and collector of ancient Welsh literature, Morganwy claimed that an age-old Welsh tradition had survived both the Roman invasion and the conversion to Christianity, but some of his ‘ancient manuscripts’ were discovered after his death to be documents he’d forged. Perhaps, nonetheless, Morganwy’s lingering influence over the Dunravens encouraged them to donate some black-winged birds to the fortress built near the burial place of Bran. (From Younghusband’s book, we also have the first account of ravens being present at the execution of Anne Boleyn.)

Yet another possibility is that the Tower bought the ravens from Philip Castang, an old family firm – operating out of London’s Leadenhall Market – that sourced animals for zoos and private owners. In 1955, the firm’s manager wrote to Country Life magazine claiming he had ‘the order for the first Tower ravens’ framed and hanging on his office wall. Frustratingly, the company has now closed, the manager has died and the order has vanished.

Place of Execution in Front of St Peter’s Chapel, H.E. Tidmarsh (1900), the fourth earliest-known visual depiction of a raven in the Tower of London

Sources from the turn of the 20th century begin to mention the ‘tradition’ that a set number of ravens must be kept in the Tower. The 1898 book Birds of London states ‘for many years past two or three ravens have usually been kept at the Tower of London’ while an essay from 1904 proclaims ‘five pet ravens may be seen in ominous proximity to the Block … The ravens, which haunt the locality with dismal croaks, are a private gift to the Tower, and should one die it is replaced by the donor.’

Five does seem to have been the number settled on around this time. An intriguing account of a visit to the Tower comes from the Japanese writer Natsume Soseki, who toured the fortress on Halloween in 1900. Soseki might best be understood as a Japanese equivalent to someone like James Joyce, with his work blending the fantastical and everyday in a sort of early magical realism. Soseki’s portrayal of his visit has him seeing the ghosts of Walter Raleigh, Lady Jane Grey, Guy Fawkes and the two princes murdered by Richard III, but he also describes the ravens and insists there are five. When he returns to his lodgings, he tells his landlord about his excursion. The landlord responds, ‘There were five ravens there, I suppose … They’re sacred ravens. They’ve been keeping them there since ancient times and, even if they become one short, they immediately make the numbers up again. There are always five ravens there.’

So, from these sources, we can see the idea emerging, around 1900, that a certain number of ravens have long been kept in the Tower and that if one dies or disappears, it must be replaced. But – although we would assume there must be some reason for this ‘timeless custom’ – none of these sources seem to give it. When then, could we say with certainty, does the notion arise that the ravens vanishing will mean the collapse of the Tower, the monarchy and the nation?

The earliest-known mentions of such a legend are from World War II. The story about Charles II ordering that six ravens be kept in the Tower cannot be traced back any earlier than 1944. This didn’t, however, stop this tale finding its way into the Oxford Dictionary of Folklore, published in 2000. The War also appears to have seen the ‘optimal’ number of ravens raised from five to seven. The idea of Churchill stepping in to boost a dwindling population may also be untrue. Legend claims that, by the time the War was nearly over, just one pair of ravens – Grip and Mabel – had managed to hang on. But it seems that shortly before the Tower’s reopening, the two ravens absconded for a nearby wood. Parnell found a note in the Tower’s records solemnly stating ‘there are none left’. Though the Tower, monarchy and British state all remained intact, some blame the post-War loss of the British Empire on the ravens’ escape.

So, What’s the Conclusion? Is the Tower of London’s Raven Legend a Recent Invention or Ancient Myth?

Although it’s likely that in centuries gone by London’s ubiquitous wild ravens would have frequented the Tower – and may have been drawn to the executions of its inmates – the ‘tradition’ of deliberately keeping ravens in the Tower of London doesn’t seem to have arisen until the later 1800s. Around 1900, the notion grew up that a set number of the birds must be maintained in the stronghold. The idea the ravens’ departure would mean catastrophe for the nation may have also originated around this time, but no sources appear to actually state this until World War II.

It seems, then, that the Tower of London’s raven myth is a recent one, but we might ask why such a strange belief emerged in the Victorian era and the first half of the 20th century. In his book The Invention of Tradition (1994), the historian Eric Hobsbawn argued that modern states often claim that their pageantry, customs and legends are ‘rooted in the remotest antiquity’. Such claims have the effect of making modern nations seem ‘the opposite of constructed, namely human communities so “natural” as to require no definition.’ Such notions become particularly insistent during times of upheaval, stress and change.

In the Victorian age, Britain underwent enormous and rapid urbanisation, industrialisation and technological advancement, as well as a dizzying realignment of the class structure as the upper-middle class surged, the aristocracy weakened, and a growing and disenfranchised working class started to demand their rights. There was also the pressure of maintaining a huge overseas empire and the wars of conquest and brutal suppressions of native peoples that entailed. Faced with such challenges, it must have been tempting to try to claim that Britain and its empire were organised on age-old principals stretching back into misty antiquity and that just under the grimy surface of the Victorian industrial world could be found quaint traditions and a stable hierarchy that had lasted for centuries. There were, for example, assertions that breeds of dogs and other animals were far older than they really were and an often automatic assumption that folkloric dances and ceremonies sprang from an ancient, even pagan past.

There was also a massive vogue in Victorian art, literature and architecture for the medieval and folkloric, an obsession whose influence was felt in the Tower of London. These obsessions were strong enough to survive the death of Victoria herself in 1901 and to continue for some time into the 20th century. The Tower of London and its developing raven myth fitted well into all this. Wrapped up in the imagined continuity of this colony of birds were England’s age-old monarchy and echoes of a feudal era of secure social relations – an era whose black-winged mascots could still be seen hopping about in the present day. In addition to that, the birds added drama to the (recently enhanced) gothic theme park of the Tower with its tales of imprisonment and bloody execution, which all bestowed pleasing frissons of horror on a pleasant Victorian or Edwardian day out.

An ‘executioner’s block’ at the Tower of London – its gruesome history of beheadings has always proved popular with tourists. (Photo: Stephen Gellion)

It’s interesting that the Tower of London’s raven legend got a boost in World War II, when the nation was under serious threat. A number of myths seem to have either arisen or been strengthened on our besieged island at this time. As well as the invention, or at least reinforcement, of the legend about the ravens fleeing the Tower, a bizarre belief grew up that the Celtic queen Boudicca – who’d rebelled against Roman rule – was buried under a platform at Kings Cross Station.

But maybe all this is too cynical. I’m of the opinion that – although the Tower’s raven legend developed in fairly recent times in response to social and political stresses – the myth does draw on earlier folklore and deeply held archetypes. The raven’s associations with monarchy, prophecy, execution and death are all apparent in how the bird has been depicted at the Tower and the Tower’s raven legend might well display the human tendency to believe our wellbeing and even survival can be invested in some external object. There’s also the legend of Bran’s head – which at least may have prompted the Dunravens to donate ravens to the Tower – and the strange mythic significance that Tower Hill has accumulated through the centuries.

Perhaps such a strategic spot as Tower Hill, and such a crucial building as the Tower, will always have the tendency to generate myth. Tower Hill lies close to the lowest points at which – for many centuries – the vital thoroughfare of the Thames could be bridged or forded, making it a natural spot from which to control trade or resist invasion. And the Tower itself was for centuries probably the most vital building for upholding the British monarchy and state. It’s served as a royal palace, an armoury, a barracks and – of course – a jail for elite prisoners suspected of plotting to bring the monarch down. The Tower of London was also for many years the Royal Mint – performing the essential function of distributing, and maintaining the quality of, the coinage of the realm. In the fortress’s Byward Tower, a medieval religious mural – promising the fires of hell to thieves and fraudsters – once looked over the room where merchants brought in their gold bullion to sell to the Crown. The Tower also watched over the crucial trading settlement of the City of London, seen by monarchs as both a potential centre of revolt and a cash cow to be milked via taxation. Even today, tensions arise between the government and the City over issues like tax avoidance, banking regulation and money laundering.

It’s no surprise that the Tower and its environs, having been symbolic for years of power structures and important government interests, have had myths woven around them. And when one considers the deep folklore of the sinister and cunning raven, it’s perhaps also no shock that some manifestations of the Tower’s mythology have been embodied in these hopping, croaking and mischievous birds.

(This article’s main image, showing the ravens Jubilee and Muninn at the Tower of London, is courtesy of Colin.)

Leave A Comment