Many of us feel we’re familiar with Christmas, but the more you peer into the history of the festival, the stranger it can seem. Do you know that a number of ancient gods jostled to claim Jesus’s birthday or that many of our deeply held Yuletide traditions were thrown together in just a few years by enthusiastic Victorians? Over the centuries, Christmas has involved hymn-humming insects, pious cows, talking animals and bits of charred wood that protect us from witchcraft and lightning. Yes, Christmas can seem pretty odd, so come with me and let me tell you six strange facts about Christmas.

Strange Christmas Fact 1: Ancient Origins

Our midwinter celebration has ancient origins. The – probably religious – monuments of Newgrange in Ireland and Stonehenge in England are aligned to the sunrise and sunset on the midwinter solstice (21st December). In ancient Rome, Saturnalia, a festival of feasting, drinking and gift giving in honour of the god Saturn, ran from December 17th to 23rd. The Romans saw 25th December (which they wrongly reckoned to be the solstice) as the birthday of the All-Conquering Sun. The idea that the sun dies and is reborn at his weakest point in the year was common among traditional peoples, who perhaps also held the notion that their festivities could urge the sun on through the coming cold months as he slowly strengthened in the sky.

Stonehenge on the Winter Solstice

The Vikings and Germanic peoples celebrated a 12-day midwinter festival, sometimes called Yule, which involved feasting, drinking and possibly human sacrifice. There are several reasons why midwinter would have been a time for festivities. It was the last chance for a feast before the onset of deep winter, in which people might starve. Animals were slaughtered so they wouldn’t need to be fed in the winter, which meant there was a plentiful supply of meat. There was also a good supply of wine and beer as enough time would have passed following the harvest for these beverages to have fermented and be ready to drink. Our forebears would have likely snatched the chance to party while they could whilst hoping the weak sun would begin to burn brighter and get them through the freezing days ahead.

Strange Christmas Fact 2: The Gods All Want the Same Birthday

25th December was the birthday of a number of ancient gods, such as Mithras, Horus, Osiris, Attis, Heracles, Dionysus and Adonis. Several of these characters were also born of virgins, including Mithras (a god of light popular with Roman soldiers). Mithras’s birth attracted shepherds and magi, who – like in the story of Christ – brought gifts. As with Jesus, stars and heavenly lights foretold the birth of the Buddha as well as the births of several Roman emperors. These stories may have influenced accounts of Christ’s nativity or they may just reflect common archetypes associated with the births of heroic figures.

The Star of Bethlehem by Edward Burne-Jones, completed in 1890

The Church most likely commandeered the 25th to win pagan converts. The Bible is unclear about when Christ was born and contains no commandments to celebrate his birthday, but the Church probably felt making the deep-rooted midwinter festival a part of the Christian calendar was too valuable an opportunity to miss.

Strange Christmas Fact 3: The Victorians Resurrect and Reinvent the Festival

Having said that, much of our modern Christmas was invented – or reinvented – in the Victorian era, mainly due to the efforts of writers like Charles Dickens and Washington Irving, who had somewhat romanticised ideas about a joyful festive past. Dickens’s A Christmas Carol painted an image of Christmas as full of gift giving, games, feasting and good cheer. But – though Christmas had been a popular medieval and Tudor festival – by the early Victorian period, it was in danger of dying out.

On Christmas Day 1843, the year Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol, The Times was published as normal. It made no mention of Christmas and it had barely mentioned the festivity for the previous 25 years. Dickens was in the habit of tramping miles through London’s streets in feverish midnight walks, but few of the streets he strode along would have been hung with Christmas decorations and Dickens would have seen little more cheer than that usually supplied by the city’s pubs and gin palaces. But A Christmas Carol – a small, lovingly illustrated book that Dickens, with his commercial savvy, hoped would make an excellent Christmas present – proved amazingly popular, selling out its first print run of 6,000 in just five days.

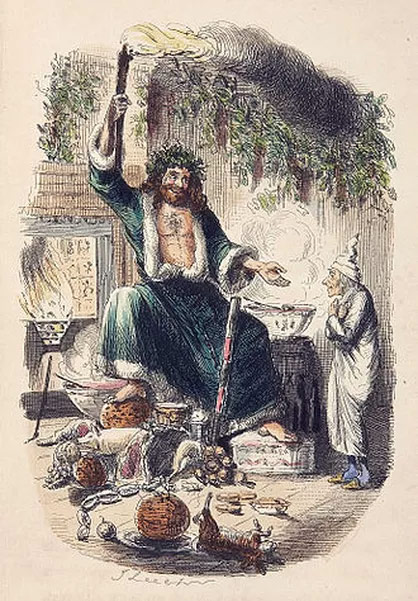

The Ghost of Christmas Present, a hand-coloured etching in the first edition of A Christmas Carol

Victorians were soon decorating their houses, indulging in Christmas games, exchanging presents (though gifts had traditionally been given at New Year rather than Christmas) and enjoying sumptuous Christmas dinners. When Dickens died, one young girl was overheard asking, ‘Daddy, does that mean there won’t be Christmas anymore?’ Even the phrase ‘Merry Christmas’ was popularised by A Christmas Carol.

Strange Christmas Fact 4: Many Christmas ‘Traditions’ Are Victorian Innovations

Many ‘traditional’ parts of the British and American Christmas are Victorian-era inventions. The first Christmas card was produced in 1843 and 30 years later four million were being sent annually. The Christmas cracker was invented in 1847 by a London confectioner who got the idea from the packaging of French bon-bons and from watching a log crackling and snapping on the fire.

Christmas crackers were a Victorian invention

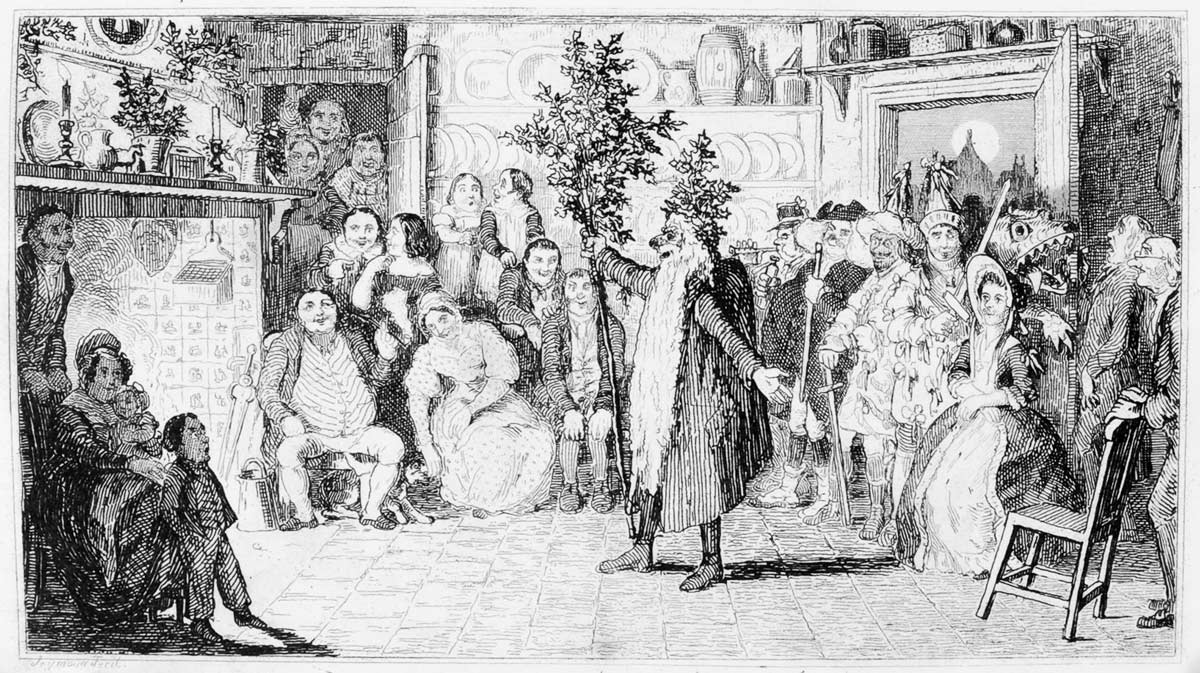

An 1848 print of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and family gathered round a Christmas tree helped spread to Britain the tree-decorating custom that had originated in Albert’s Central European homeland.

The popular 1848 print of Victoria, Albert and their Christmas tree

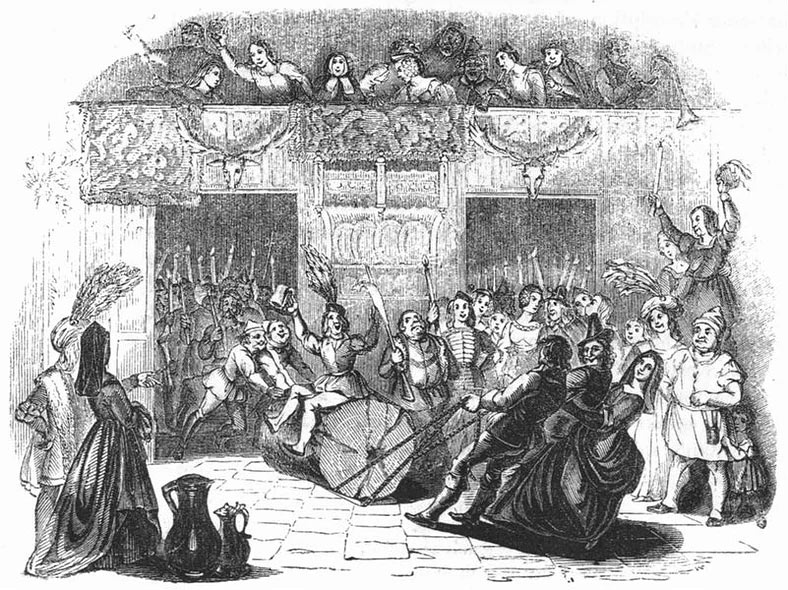

In A Christmas Carol, a reformed Scrooge sent a turkey to the home of his mistreated clerk Bob Cratchit, helping to trigger the turkey’s transformation from an exotic bird enjoyed at aristocratic feasts into a staple of the middle-class Christmas dinner. The figure of Santa Claus as a red-suited, sleigh-driving gift giver was created in New York between the mid-1800 and early-1900s. The, originally separate, English character of Old Father Christmas – an anti-Puritan figure who insisted on festive merriment and good cheer – dates back to the English Civil War (1642-51).

The Father Christmas/Santa Claus character evolved in the Victorian era

Strange Christmas Fact 5: Christmas Superstitions

Our fifth strange Christmas fact concerns Yuletide superstitions. It was said a person born on Christmas Day was exceptionally lucky, would never see ghosts or spirits and would never die by drowning or being hanged. As with Halloween, Christmas had strong associations with the supernatural and was a popular time for ghost stories. Unlike Halloween, however, Christmas Day was thought of as the time when ghosts, goblins and witches had the least power. Because these malign forces were kept at bay, Christmas was a good time for divination. In Derbyshire, it was said that ‘if a girl walks backwards to a pear tree on Christmas Eve, and walks round the tree three times, she will see an image of her future husband.’

The idea the natural world reflected the Christian calendar was strong. In Britain, it was said that on Christmas Eve bees hummed the 100th psalm and cattle knelt in their stalls to honour Christ. When the calendar changed in 1752, older cows apparently continued to kneel on Old Christmas Eve (January 5th) while younger beasts took up the new custom and knelt on 24th December. Another superstition stated that on Christmas Night animals had the ability to talk.

Strange Christmas Fact 6: The Magical Yule Log

Nowadays many people enjoy eating a chocolate Yule log, but the Yule log used to be a large piece of wood that was ritually burnt on the fire on Christmas Eve. It was believed that the log should burn all night, but it was important that not all of it was consumed. A piece was saved, kept in the house and used to kindle the Christmas fire the following year.

This charred bit of wood – probably on the principle of sympathetic magic – was viewed as a protection against fire and lightning. In parts of northern Europe, a piece of the log was put on the fire whenever there was a thunderstorm. The Yule log was normally of oak and there may have been a connection with ancient beliefs associating this tree with the god of thunder. The oak is the tree most likely to be struck by lightning – a fact that may be linked to notions the Yule log could guard against such a danger.

More strange Christmas folklore was connected with the Yule Log. A part of the charred brand could be ground to powder and strewn over the fields to boost their fertility. In some regions, pieces were put in corn bins to keep away mice. The remains of the Yule log were also said to protect against witchcraft.

A somewhat romanticised Victorian depiction of a Yule log being dragged into a baronial hall

I hope you have enjoyed these strange facts about Christmas and that you have a most merry Yuletide and Happy New Year.

Leave A Comment