We may think there’s nothing that unusual about the ‘typical British churchyard’. The lines of worn and lichen-spotted gravestones, the land made bumpy by centuries of burials, the narrow path winding between the tombs and the great dark bulk of the church looming over it all might seem so familiar as to hardly incite comment.

But churchyards can be the strangest and most gothic of places – outdoor emporiums of the weird, walled collections of the bizarre. What if I were to tell you that churchyards harbour oddities as striking as standing stones and stone circles, statues of pagan goddesses, smouldering footprints left by the Devil, ships’ figureheads acting as grave markers, and slabs on which corpses were laid so the vicar could check they were appropriately attired?

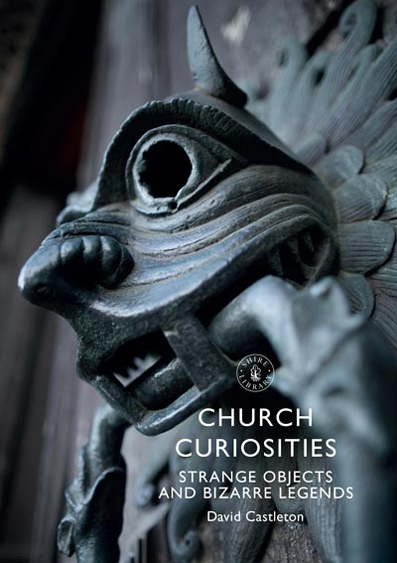

While researching my latest book – Church Curiosities: Strange Objects and Bizarre Legends (Shire/Bloomsbury) – I was constantly amazed by just how thoroughly odd the artefacts lurking in our churches and churchyards can be and how peculiar and intriguing the bits of folklore linked to them are. So read on to learn about ancient stones said to act as direct telephone lines to His Satanic Majesty, elaborate Victorian carts for transporting coffins, dinosaur footprints, and evidence of infernal games of leapfrog. Below are seven truly weird features of British churchyards.

Number One: Standing Stones and Stone Circles in British Churchyards

It’s strange to think that standing stones – objects associated with paganism – might lurk in the very Christian precincts of churchyards. Here and there, however, these enigmatic objects crop up. Evidence suggests many churches were built on pagan sites, with several – for instance – found within earthworks and henges, on manmade mounds or even topping barrows. This could have been a means of the new religion asserting its dominance over the old, of cleansing the neighbourhood of the influence of the old gods and of benefitting from any reverence the populace felt for such locations. Though the erectors of standing stones and builders of stone circles had disappeared long before Christianity came to these islands – and the stones were probably as mysterious to later pagans as they are to us today – it’s likely that these monuments still exerted awe over people’s minds. Taboos against damaging standing stones and burial mounds persisted into the 1800s, with one farmer on the Isle of Man recorded as sacrificing a calf before he dared disturb a barrow.

In Midmar Churchyard, Aberdeenshire, there’s not only a standing stone but an entire stone circle. The Bronze-Age circle, estimated to be around 4,000 years old, has a diameter of 17 metres, with some of the stones reaching 2.5 metres in height. This mysterious ring – whose stones contrast oddly with the later Christian grave markers – is one of Scotland’s best-preserved recumbent stone circles. In ‘recumbent’ circles, the largest stone is positioned ‘lying down’, with the two tallest stones usually flanking it – an arrangement that has led to descriptions of the Midmar Circle as ‘fanglike and demonic’. The Midmar area appears to have been a site of religious importance, as two more stone circles lie to the east and south-east of the village and other standing stones scatter the locality. Many of these stones are of a similar date and one of the other circles is also recumbent.

Midmar Stone Circle, in Midmar Kirkyard, Aberdeenshire – fanglike and demonic? (Photo: Silent Earth)

A Welsh church – St John the Baptist’s, in Ysbyty Cynfyn, Ceredigion – may have been built inside a stone circle. The round churchyard wall incorporates several standing stones, with two even serving as gateposts. More stones litter the churchyard and nearby fields and the church is ringed by a low earthen bank, all of which suggest a once significant monument. The current church is 19th century, but in the Middle Ages a hospice run by the Knights Hospitaller stood on the site. The Welsh Ysbyty translates as ‘hospital’.

A large standing stone in the wall of St John the Baptist’s Churchyard, Ysbyty Cynfyn, Ceredigion. (Photo: Scribblah)

Near the porch of St Twrog’s Church, Maentwrog, Gwynedd, is a standing stone that St Twrog apparently hurled from the Moelwyn Mountains to crush a pagan altar. The handprint of St Twrog – who seems to have boasted characteristics of both a saint and giant – is said to mark the stone. A superstition claims that if you rub the stone, you’ll one day return to Maentwrog. Another belief states that the stone indicates the grave of Pryderi, a legendary king from the Welsh cycle of myth the Mabinogion.

Standing stone in St Twrog’s Churchyard, Gywnedd – hurled by the saint or the gravestone of a mythical king? (Photo: The Modern Anitiquarian)

A 1.75-metre-high standing stone – which may have once been even taller as its upper section seems to have been broken off – guards the porch of St Gwrthwl’s Church, Llanwrthwl, Powys. The stone – which may be over 4,000 years old – might have prompted St Gwrthwl to build the first church on the site to take advantage of its spiritual associations.

The most famous – and imposing – standing stone in a British churchyard, however, has to be the Rudston Monolith, which looms next to All Saints’ Church, in Rudston, East Yorkshire. The monolith – a towering eight metres – is Britain’s tallest standing stone. The gritstone megalith – which weighs in at 40 tonnes – was studied by the antiquarian, early archaeologist and druid-obsessive William Stukeley (1687-1785). Stukeley dug around the stone and concluded it went as far into the ground as it protruded above it. Stukeley also claimed he’d found human remains buried around the monolith, indicating it was a focus of human sacrifice. Though such assertions might be far-fetched, the Rudston Monolith may well have been the centre of a ‘ritual landscape’. Henges, barrows, earthworks and traces of ancient settlements dot the vicinity and three cursuses – long, manmade trenches or ditches – converge towards the monolith. The monolith dates from the early Bronze Age or late Neolithic times, meaning it would have been set up at least 2,500 years before its site became a place of Christian worship. The name ‘Rudston’ – probably meaning ‘cross stone’ – hints at a pagan monument being adapted for Christian uses.

The Rudston Monolith in Rudston Churchyard, East Yorkshire – Britain’s tallest standing stone. (Photo: Stephen Horncastle)

Such a huge and bizarre artefact has, unsurprisingly, generated legends. One tale claims the monolith was a missile hurled by the Devil to demolish All Saints’ Church. Divine intervention deflected this diabolical projectile and the monolith embedded itself harmlessly among the graves. Another piece of folklore states the monolith dropped from the clouds, squishing some sinners who were desecrating the churchyard. This story might have grown out of garbled memories of a meteorite that fell at the nearby village of Wold Newton in 1795, landing with a colossal bang and missing a labourer by just ten yards. Though the Rudston Monolith isn’t a meteorite, its gritstone doesn’t match up with the rock types of the immediate area. The monument must have either been carved from a glacial erratic or dragged from 10-to-20 miles away, an astounding achievement considering the technology of the time. Yet another local tradition maintains there’s a dinosaur footprint on the megalith’s side, but this long-held belief was debunked by a 2015 English Heritage survey.

Number Two: Seafarers’ Graves in British Churchyards

Surrounded by ocean, Britain has long been a seafaring country and a number of churchyards reflect this fact. Unsurprisingly, Cornwall – with its miles of rugged and dangerous coast – hosts some unusual monuments honouring those who earned a hazardous living on the waves.

In the village of Morwenstow, a most unusual carving can be seen in the churchyard – a woman holding up a shield and brandishing a sword. In 1843, a Scottish ship named the Caledonia went down close the village, with 40 crew members perishing. Their bodies were interred in Morwenstow’s clifftop churchyard and the ship’s figurehead – salvaged from the wreck – was set up as their grave marker. Legend says if you walk too close to the figurehead at night, its sword will slash at you. The figurehead now in the graveyard is a replica – the worn original has been moved inside the church.

The figurehead of the Caledonia, in Morwenstow Churchyard – a grave marker for the ship’s unfortunate crew. (Photo: Easymalc’s Wanderings)

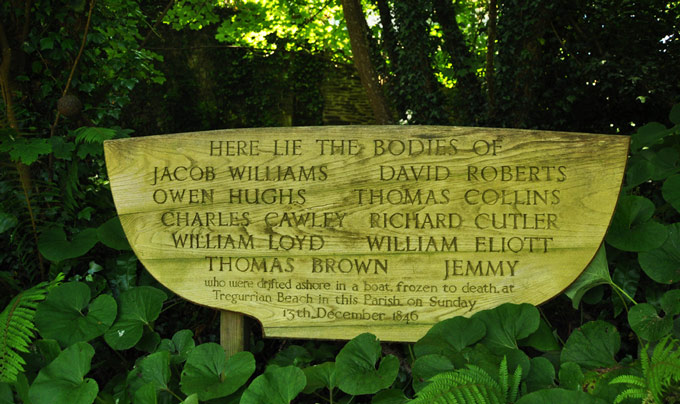

Another nautical ‘tombstone’ can be found in the churchyard of the Cornish village of St Mawgan. In 1846, 10 sailors were found frozen to death, drifted ashore in a boat. The boat’s stern was carved with their names and set up to mark their resting place.

In St Mawgan’s Churchyard, Cornwall, a boat’s stern serves as a grave marker for a group of sailors found frozen to death. (Photo: I Walk Cornwall)

At Veryan, Cornwall, 19 German sailors from a ship that sank in 1914 are buried in a single line head-to-toe, in a grave that’s an incredible 40 metres in length. The grave is thought to be the longest of its type in Britain.

A sailors’ grave – containing 19 crew members buried head-to-toe – in Veryan Churchyard, Cornwall. (Photo: CornwallLive)

Number Three: Lychgates in British Churchyards

I’m sure you’ve noticed that many British churchyards have a porch-like, pointy-roofed structure over their entrance. I suspect you might have also wondered about the purpose of these unusual buildings. These porch-like constructions are known as lychgates and once had a rather macabre function.

‘Lich’ is Old English for ‘corpse’ and corpses were laid under the lychgate to await the priest before funerals. The first part of the funeral service was also conducted beneath the structure. You can still see seats at the sides of some lychgates for pallbearers and mourners. In the Middle Ages, before mortuaries were widespread, bodies could be kept under the lychgate for up to two days. The lychgate would keep the rain off and the seats would have no doubt been a welcome feature for those watching over the corpse.

Medieval lychgate in St George’s Churchyard, Beckenham, South London. (Photo: Wheeltapper)

Under some lychgates are low, long platforms known as lych-stones. The lych-stone was where the body – sometimes coffined, sometimes just shrouded – rested. Between 1666 and 1814, an official – usually the parish priest – was obliged to inspect the corpse as it lay there. This was to ensure the body was wrapped in a woollen shroud. It was a legal requirement that corpses be dressed in this way – a measure introduced to protect the wool trade. (In many places, however, it seems this rule was ignored.)

Though most medieval lychgates have rotted away, a few can still be seen, such as at St George’s Church, in Beckenham, South London. St George’s 13th-century lychgate is thought to be England’s oldest. At St Euny’s Church, Redruth, Cornwall, is a remarkably long lych-stone. It was designed to support three coffins because accidents in the local tin-mining industry sometimes necessitated multiple funerals.

Long lych-stone in St Euny’s Churchyard, Redruth, Cornwall (Photo: Tim Green)

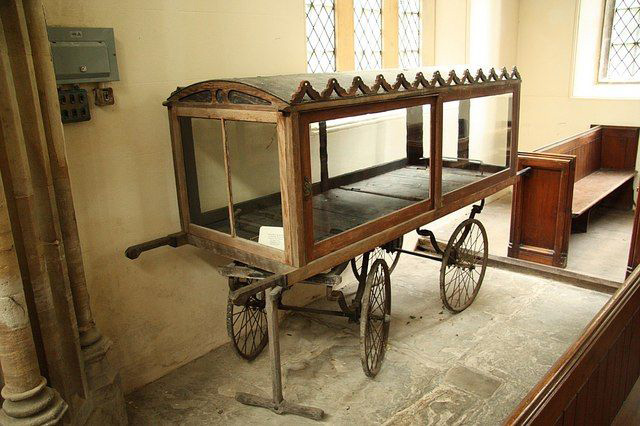

Number Four: Funeral Biers in British Churchyards (and Churches)

In and around certain churchyards, you might spot small, curious house-like structures. In St George’s Churchyard, Beckington, Somerset, is a building just one metre high with gothic-looking double doors while opposite St Peter and St Paul’s Church, Ospringe, Kent, stands a puzzling construction – with arched doorway and slit window – looking like some ominous stone-built garden shed. These ‘gothic garages’ are known as bier houses and once stored funeral biers – the four-wheeled trolleys that transported the bodies of parishioners on their journey to the grave.

A bier house opposite St Peter and St Paul’s Churchyard, Ospringe, Kent (Photo: Penny Mayes)

Many parishes had their own bier and these elderly implements can still be seen in certain churches and churchyards. Some churches have found creative uses for these objects. At Norton, Powys, a bier displays leaflets, notices and collection boxes whereas a bier in Balsham, Cambridgeshire, supports a scale model of the church. At Harvington, Worcestershire, and at Hampsthwaite, Yorkshire, biers have done duty in the churchyard as bases for floral displays. Fine Victorian briers can be seen at the Old Church of St Bartholomew, Botley, Hampshire; at St Lawrence’s Church, Evesham, Worcestershire; and at All Saints’, Holdenby, Northamptonshire.

A fine Victorian funeral bier in Botley Old Church, Hampshire (Photo: Helen Banham)

Victorian funeral bier in St Lawrence’s Church, Evesham, Worcestershire. (Photo: Richard Croft)

Bier supporting a floral display in Hampsthwaite Churchyard, Yorkshire. Unfortunately, in 2013 vandals made off with the wheels. (Photo: Hampsthwaite Village)

Number Five: Goddesses in British Churchyards

In Braunston-in-Rutland, in 1920, it was decided that the doorstep of All Saints’ Church needed replacing. The worn stone was levered up – to reveal a most curious carving on its other side, an image that had spent unknown centuries being pressed into the mud by the feet of generations of worshippers. The carving is of a female figure with protruding eyes, rubbery lips, a sticking-out tongue, ‘double nose’ and pert breasts. This intriguing character now leans against the church’s tower.

The mysterious Braunston Goddess, in Braunston-in-Rutland Churchyard (Photo: SiGarb)

Though the carving has acquired the title the ‘Braunston Goddess’, it’s not known what period she comes from or what she was intended to represent. She isn’t a gargoyle and bears little resemblance to any known style of carving though she does have some slight similarities to Sheela-na-gigs and ‘hunkie-punk’ church grotesques. There have been several attempts to explain the sculpture – that she’s a medieval ‘guardian’ of the type placed over doorways and windows to frighten off evil spirits or that she might depict a queen or even a whore. Others suggest the ‘goddess’ may pre-date the church and that she could be a fertility symbol or Celtic deity. A different hypothesis is that she might have functioned as a tribal boundary marker, placed on a border that roughly corresponded to the modern frontiers of Rutland and Leicestershire. Unless more evidence appears, however, the origins and purpose of this ‘goddess’ will remain questions we can only guess at.

Though it’s debatable whether the Braunston Goddess is a remnant of pagan antiquity, another churchyard ‘goddess’ in the British Isles is undoubtedly pre-Christian. Just outside the gate of St Martin’s Churchyard, Guernsey, stands La Gràn’Mère du Chim’tière (or Grandma of the Cemetery). This five-foot-five-inch statue – modestly robed though with rather prominent breasts – was probably sculpted in the Neolithic era, between about 2500 and 1800 BC. La Gràn’Mère – who may well have been carved from a standing stone – was probably also reworked in Roman times, between 100 BC and 100 AD.

Locals have long had a tradition of leaving flowers and coins around the sculpture, but these devotions so infuriated a pious churchwarden that he insisted La Gràn’Mère be destroyed. The statue was broken in half, but this so incensed the locals that they had her repaired with concrete and she continued to receive their reverence. Even today, La Gràn’Mère is a popular addition to wedding photos. The church La Gràn’Mère guards sits on the site of a Neolithic tomb shrine and the churchyard boasts two springs, one of which is said to have healing powers. But is La Gràn’Mère an entirely benevolent entity? In Folklore of Guernsey, Marie De Garis writes, ‘Looked at during the daytime, La Gràn’Mère wears a very benign look, but photographs taken by flashlight at night reveal quite a different aspect. She then looks a fierce and malevolent object.’

La Gran Mere, St Martin’s Churchyard, Guernsey. The crack indicates where she was broken in half in 1860. (Photo: Peter Kenny)

Number Six: Devil’s Footprints in British Churchyards

Many difficult-to-explain oddities in churches and churchyards – ranging from ‘witch’s cauldrons’ to the missing tips of steeples – have been blamed on the Devil, but perhaps the most dramatic mementos the Evil One has left are his smouldering footprints. In certain churchyards, you can still see these footprints today.

Legend claims that one night the Devil tried to steal a bell from the tower of St David’s, in Lanarth, Ceredigion. His efforts, however, awoke the vicar who drove him off. The Fiend leapt down into the graveyard and landed on a stone, upon which he left his fiery footprint.

The Devil is also held responsible for a 38-centimetre footprint which marks a stone near the gate of St Mary’s Churchyard, in Newington, Kent. As at Lanarth, the Evil One was determined to steal the church’s bells. He scaled the tower, put them in a sack and leapt down, landing on a stone with great force, thereby branding it with his demonic imprint. The bells, though, jolted from the sack and rolled into the nearby Libbet Stream. All attempts by villagers to retrieve the bells failed. An aged witch said that only four white cows would be able to tug the bells out. Four white cows were found and harnessed up and seemed to be successfully pulling the bells free. An onlooker, however, made a comment about a black spot on one of the cow’s noses. The bells tumbled back into the stream, disappeared beneath the water and have never been seen since. Local folklore claims the stream bubbles at the spot the bells sank and that the stone with the Devil’s footprint will spark if struck by a pebble.

Devil’s footprint found just outside the gate of Newington Churchyard, Kent, England. (Photo: Mapio)

Newington’s notorious stone is actually a prehistoric mudstone. Some locals say the stone was moved in the 1930s, after which a series of unfortunate events afflicted the village until the stone was moved again and placed next to the church. According to one superstition, if you rest your finger on top of the stone and walk around it three times, it will bring you good luck.

Number Seven: Devilish Stones in British Churchyards

A number of other unusual stones in and around British churchyards have connections with His Satanic Majesty. In Bungay, Suffolk, a mysterious rock known as the Druid’s Stone stands in St Mary’s Churchyard. Local folklore asserts this stone is a portal for contacting the Devil. If you’d like a direct line to the Fiend, you must either run around or knock on the stone 12 times. The Druid’s Stone is probably a glacial erratic brought to Bungay in the last ice age.

The Druid’s Stone, in Bungay Churchyard, Suffolk – a portal for contacting the Devil? (Photo: Ashley Dace)

At Marston Moreteyne, Bedfordshire, an intriguing stone stands in a field next to the parish church, also called St Mary’s. Legend says that one Sunday the Devil jumped down from the church then joined some local lads in said field, who were desecrating the sabbath by enjoying a sneaky game of leapfrog. The Devil enthusiastically participated in their sport and all were having a merry time until a hole in the ground opened, into which they all leapt and were never seen again. The stone indicates the place they vanished. This stone – sometimes referred to as the Devil’s Toenail – is actually a small Neolithic standing stone, a rarity in Bedfordshire. St Mary’s has a detached bell tower, a fact also blamed on the Fiend. The Devil tried to steal it, but – finding it too heavy – dropped it in the churchyard.

The Devil’s Leap Stone – also known as the Devil’s Toenail – in a field near Marston Moreteyne Churchyard, Bedfordshire, England. (Photo: Orion Air Sales)

More Oddities and Weird Artefacts in British Churches and Churchyards

The above items represent just a few of the thoroughly weird artefacts and peculiar tales I came across while researching my new best-selling book Church Curiosities: Strange Objects and Bizarre Legends (Shire/Bloomsbury). The book is bursting with examples of Britain’s eccentric heritage, ranging from golden balls placed on steeples by occultist aristocrats, to vampire graves, dragon-slaying swords and spears, and spooky collections of funeral effigies. Church Curiosities also explores bone crypts and secret tunnels, examines the mummified skulls of well-known statesmen, and highlights such oddities as preserved hearts hidden in pillars, the graves of beloved church cats, door knockers modelled on demons’ faces, burn marks left by black hellhounds, and ceremonies involving choirboys being suspended upside-down over the Thames. The book’s already hit the number one best-seller spot in three Amazon categories.

If you’d like to immerse yourself in a world of fascinating, disturbing, charming and deeply unusual artefacts, grab your copy of Church Curiosities now.

(This article’s main image – showing the Rudston Monolith – is courtesy of Colin Frankland)

What a fascinating blog. Very interesting and well researched.

Many thanks, Malc.

Brilliant article and photos!

I was reading about the megalith in Rudston churchyard in a post by Graham Phillips and thought “ can’t be many things like that” How wrong I was!

So glad to have found your site

Thank you

Thanks, Benita, glad you enjoyed my little tour through the weirdness of British churchyards

Thank you for the information. Fascinating seeing how much gets missed when visiting religious sites.

Thanks for your comment, Ann. Churches and churchyards really are full of the weirdest stuff – as I discovered when researching my book ‘Church Curiosities’.