On the night of Tuesday 20th February 1838, a young woman called Jane Alsop was startled by a violent clanging of the bell on the gate of her father’s house in Old Ford, a village on the then-outskirts of East London. She opened the gate to a man swathed in a dark cloak who claimed to be a police officer.

‘For God’s sake, bring me a light!’ the man shouted. ‘For we have caught Spring-heeled Jack here in the lane!’

Jane hurried into the house and rushed back bearing a candle. As soon as she handed the candle to the policeman, however, he flung off his cloak to reveal ‘a most hideous and frightful appearance.’

His eyes glowed like ‘red balls of fire’, and – as she trembled with terror and shock – Jane saw that he wore a large helmet and tight-fitting clothes that resembled white oilskin. The man opened his mouth and vomited a stream of blue-and-white flames in the direction of Jane’s face.

The man sprang forward, grabbed Jane and – placing her head under his arm – tore at her gown with claws that were ‘of some metallic substance’. Miss Alsop screamed, managed to slip away and ran back towards the house. The man bounded after her, caught her on the steps, mauled her arms and neck with his metal talons and wrenched out some of her hair. But Jane’s shrieks had alerted one of her sisters, who came running to help. After a short but intense struggle, the man fled.

This incident was widely reported in the newspapers, even making it into The Times. Far from being seen as an isolated attack, for those living in and around London, the Alsop case fitted into a pattern of bizarre assaults perpetrated by a man – or phantom or demon – known as Spring-heeled Jack.

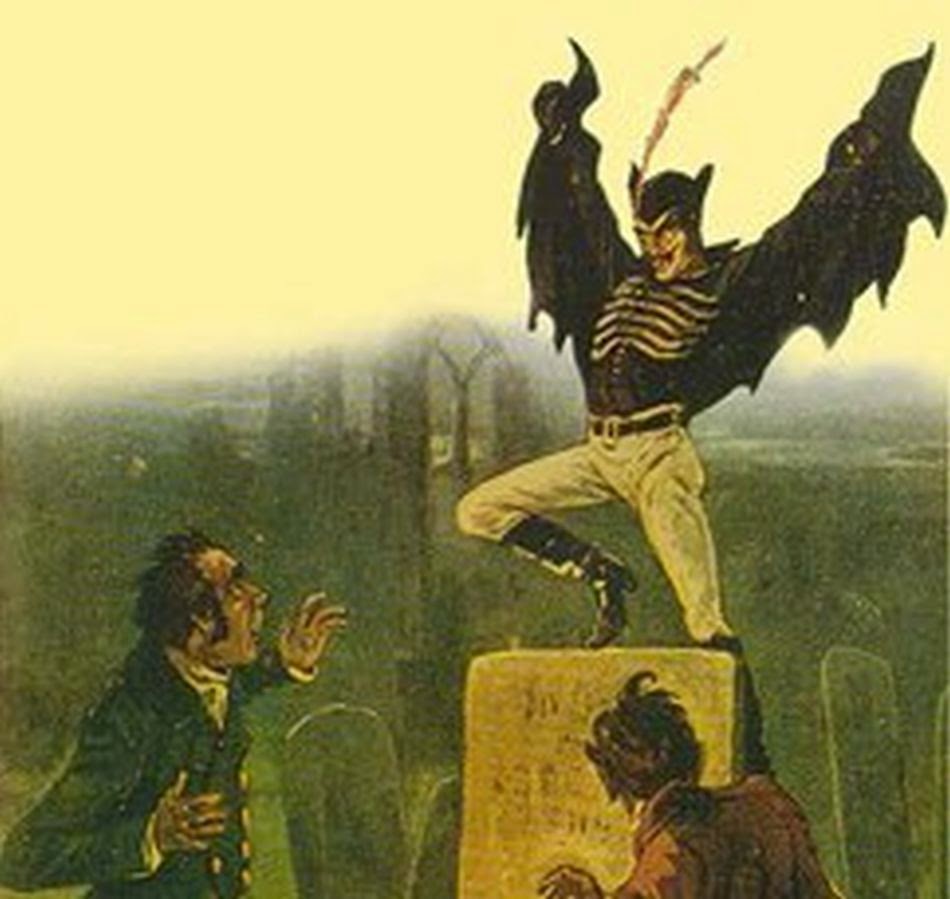

Some described Spring-heeled Jack as a ghost, some as a bear, an armoured man, a devil; others suspected he might be a dissolute aristocrat. As well as his flaming breath and burning red eyes, many claimed he had the astounding ability to spring or leap great distances, bounding over walls and hedges and even onto house roofs.

But who was this strange entity who terrorised the London area – and other parts of the country – throughout the Victorian age and beyond? Was Spring-heeled Jack just one person or several, could there have been any supernatural element involved, and how does Jack fit into an urban folklore rich with ghosts, devils and sadists – beings that many genuinely believed haunted the dark and narrow streets of 19th century Britain?

Let’s see what we can discover about the peculiar phenomenon of Spring-heeled Jack.

Spring-heeled Jack Terrorises London and Its Suburbs

The first sightings of Spring-heeled Jack occurred in 1837. In October that year, Mary Stevens, a servant girl, had been walking along the edge of Clapham Common. A tall figure jumped at Mary from a dark alley. He grabbed hold of her, tore at her clothes with claws and forced kisses on her face. His hands felt ‘cold and clammy as those of a corpse.’ Mary screamed and the attacker fled. Her cries alerted several locals, who searched for her assailant, but could find no one.

The next day, a similar figure sprang in front of a carriage. The carriage crashed and the coachman was badly injured. According to witnesses, the figure then escaped by leaping over a nine-foot (2.7-metre) wall while emitting a stream of high-pitched laughter.

News of this strange attacker soon spread through London and the surrounding settlements, and it wasn’t long before this sinister being was christened ‘Spring-heeled Jack’. The idea arose that his leaping abilities might be due to springs hidden in the heels of his boots, with newspapers like The Morning Chronicle crediting him with ‘spring shoes’.

Jack, however, didn’t always stick with his tall, jumping, metal-clawed persona. In early September 1837, a ‘ghost, imp or devil’ in form of ‘a large white bull’ was rumoured to have attacked a number of people, especially women. Over the next two months, Jack was said to have appeared in the guises of a ‘ghost, bear or devil’ in over twenty villages around London. In – the suitably named – Cut-throat Lane, Isleworth, a carpenter called Jones was attacked by Spring-heeled Jack clad in armour. Jones resisted and a fight began, but two more ‘ghosts’ joined the fracas on Jack’s side and carpenter was severely beaten.

Rumours of Spring-heeled Jack were soon terrifying London

Jack is said to have haunted St John’s Wood in late December 1837 and early January 1838 dressed in armour and in the guise of a bear. On the western edge of London, he put in an appearance as a devil armed with iron claws, with which he attacked a blacksmith and several women. There were rumours Jack had been seen climbing over the walls of Holland Park and Kensington Palace at midnight to dance ‘fantastic measures on the wooded lawns.’ A woman in Dulwich had been ‘nearly deprived of her senses’ by the sight of a ghost ‘enveloped in a white sheet and blue fire’ and a nine-year-old boy from Hammersmith had been ‘terribly frightened’ by a glimpse of Spring-heeled Jack in the shape of a bear.

Stories of Jack’s assaults kept circulating. According to one account, a servant girl, Polly Adams, was attacked on Shooter’s Hill by a man who vomited fire in her face and attempted to rip her clothes off. She suspected the man was a gentleman who’d tried to seduce her earlier the same day. London’s outskirts swarmed with rumours of a man who’d hide in unlit lanes before springing out at travellers. After accosting them, he’d escape with the most incredible leaps, sometimes clearing hedges and gates with just one bound.

With the metropolis humming with tales of this strange predator and the populace’s fear and agitation intensifying, the authorities felt they had to be seen to take action.

Spring-heeled Jack’s Outrages Prompt London’s Lord Mayor to Act

On 9th January 1838, the Lord Mayor of London announced – during a public session at the Mansion House – that he’d received a letter from ‘a resident of Peckham’. A part of the letter read:

‘It appears that some individuals (of, as the writer believes, the highest ranks of life) have laid a wager with a mysterious and foolhardy companion, that he durst not take upon himself the task of visiting many of the villages near London in three different disguises – a ghost, a bear and a devil … The wager, however, has been accepted and the unmanly villain has succeeded in depriving seven ladies of their senses, two of whom are not likely to recover …

At one house the man rang the bell, and on the servant coming to open door, this worse than brute stood in no less dreadful figure than a spectre clad most perfectly. The consequence was that the poor girl immediately swooned and has never from that moment been in her senses.’

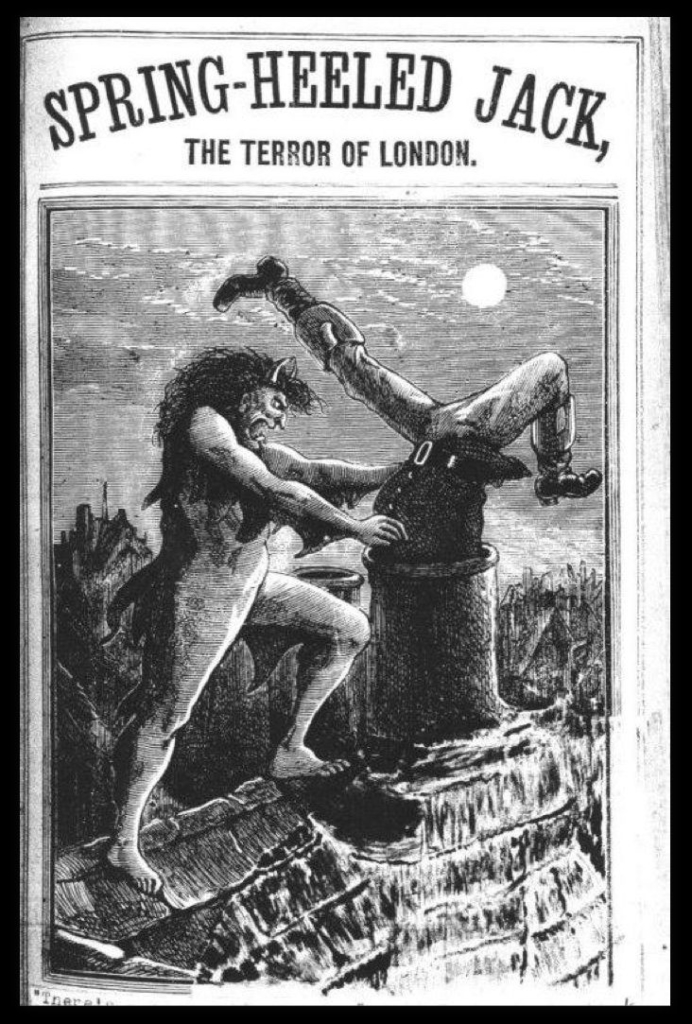

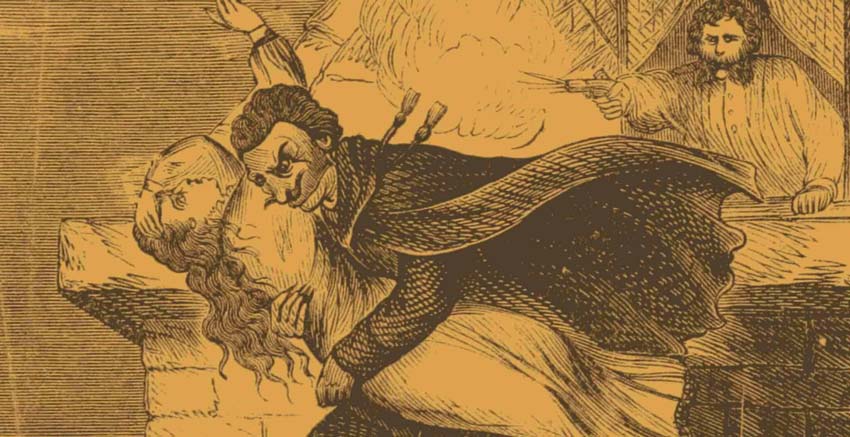

Spring-heeled Jack in his guise as a devil

Though the Lord Mayor was sceptical of such reports, members of his audience told him that ‘servant girls around Kensington, Hammersmith and Ealing tell dreadful stories of this ghost or devil.’ The revelations from the Lord Mayor’s meeting were reported in The Times on the same day and in a number of other papers on January 10th. On the 11th, the mayor showed another meeting – packed with anxious citizens – a heap of letters detailing similar ‘wicked pranks’ committed in and around London.

One correspondent claimed Jack had frightened several women into ‘dangerous fits’ in the Hammersmith area and another asserted that in Brixton, Stockwell and Vauxhall people had even died of fright upon encountering the monster. One writer claimed Spring-heeled Jack had been spotted several times in Lewisham and Blackheath. Another complainant stated that a servant girl in Forest Hill had been sent into fits by a figure in a bear’s skin.

There were especially strong rumours about a gang of aristocratic ‘rascals connected to high families.’ Letters alleged ‘that bets to the amount of £5,000 are at stake upon the success or failure of the abominable proceedings’ and that the ‘object of the villains is to destroy the lives of not less than 30 human beings! Viz eight old bachelors, 10 old maids and six ladies’ maids, and as many servant girls as they can, by depriving them of their reason, and otherwise accelerating their deaths.’

The mayor still thought the hysteria around Spring-heeled Jack had inspired the ‘greatest exaggerations’ and said he doubted that ‘the ghost performs the feats of a devil upon earth’. But he promised that the man responsible for these ‘pantomime displays’ would be apprehended and punished. The mayor instructed the police to search for the culprit and offered rewards for information leading to his capture.

Spring-heeled Jack Gains More Infamy and Commits Fresh Crimes

In spite of the mayor’s determination to catch Spring-heeled Jack, reports of fresh outrages kept coming in. On 20th February 1838, the attack on Jane Alsop occurred and on 28th February another young woman, Lucy Scales, was the victim of a similar assault. Lucy and her sister were walking through Limehouse, passing along Green Dragon Alley, when they saw a person in a large cloak standing in that narrow thoroughfare.

As Lucy passed the person, he vomited ‘a quantity of blue flame into her face’, temporarily blinding her. Lucy fell to the ground and began having violent fits, which would go on for several hours. Lucy’s assailant, who hadn’t attempted to touch her, then strode away. He was described as being tall, thin and of gentlemanly appearance, to have been carrying a lamp similar to those used by the police and to have been wearing some sort of headgear.

A few days later, in East London’s Turner Street, off Commercial Road, a servant boy responded to a vigorous knocking on his master’s door. He opened it to see a man wrapped in a cloak. The man threw his cloak back to reveal a bizarre costume and hideous features similar to those that had confronted Jane Alsop. The boy screamed so loudly it caused the man to flee. As the man turned to run, the boy is said to have noticed the letter ‘W’ embroidered on his cloak as part of an ornate, aristocratic-looking crest.

After the attacks on Jane Alsop and Lucy Scales, a number of suspects were arrested and questioned, but all were let go. The man most strongly suspected of being Spring-heeled Jack was one Thomas Millbank, a carpenter who lived near the Alsops. Millbank – who had apparently made drunken boasts of carrying out the Alsop assault and had been wearing white overalls and a greatcoat on the day it occurred – escaped being charged because the police were convinced he had no ability to breathe fire. Millbank had also been drunk on the night of the attack and Jane and her sister insisted their assailant was sober.

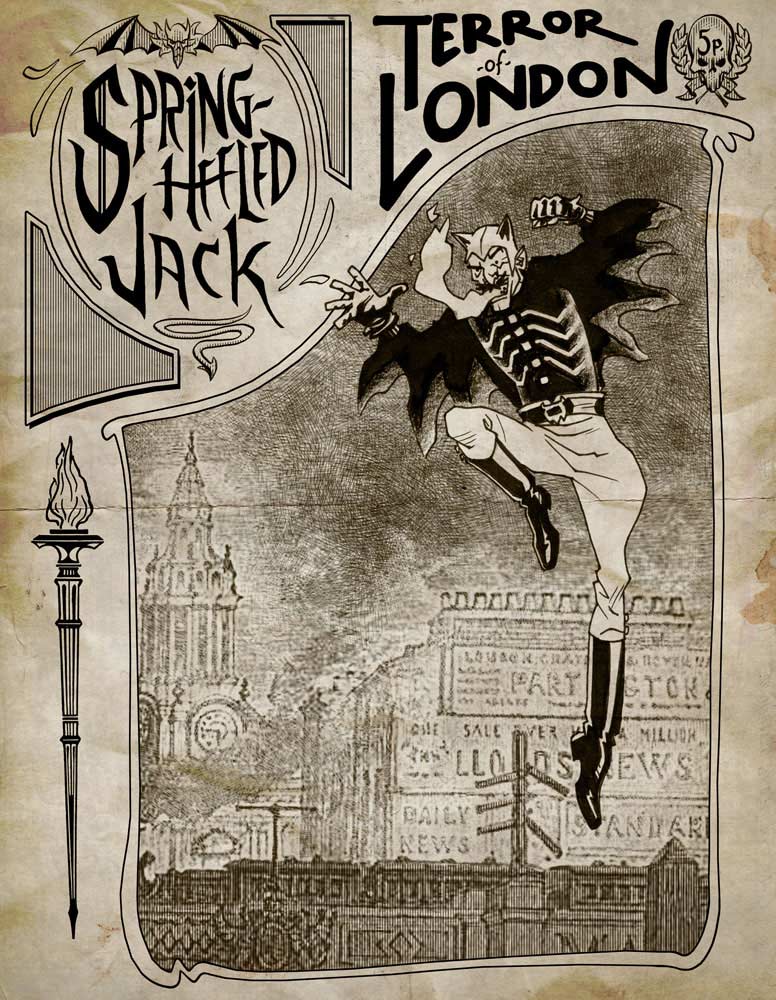

Spring-heeled Jack, as depicted in a penny dreadful of 1890

The assaults by Spring-heeled Jack – or, due to his growing fame, those imitating him – went on. On 28th February 1838, a well-dressed man informed the landlady of the White Lion pub in Vere Street that he was Spring-heeled Jack. The man then produced a club and swung it at a group of women. A man dressed in a cloak seized hold of a lady in Lincoln’s Inn Fields and slapped her face, and in Islington a blacksmith called James Priest was arrested after attacking a number of females. Priest was given three months’ hard labour. In March, two tall men in dark cloaks – their faces painted with ochre – frightened a boy in Westmoreland Mews. In Kentish Town, a youth was cautioned after being caught with a mask with blue glazed paper arranged around its mouth – paper meant to mimic Jack’s flaming breath. A Kilburn man was fined four pounds after pulling off several pranks wearing a bearded mask and sheet.

Spring-heeled Jack was also becoming more active outside the capital. In April, a woman was attacked on the cliff tops at Southend by a ‘gentleman’ who ripped her clothes and shoved grass into her mouth, prompting the local paper to run the headline ‘Spring-heeled Jack at Southend’. On 14th April 1838, an article in the Brighton Gazette claimed that a gardener in Rose Hill, Sussex, had been terrified by a being ‘in the shape of a bear or some other four-footed animal.’ After startling the gardener with a growl, the ‘bear’ had scaled a wall and trotted along it on all fours before leaping down and chasing the gardener. The ‘animal’ then clambered over the wall and made its escape. This incident was picked up by The Times, with the newspaper commenting, ‘Spring-heeled Jack has, it seems, found his way down to the Sussex coast.’

Spring-heeled Jack, meanwhile, was turning into a figure of urban legend. As well as his frequent appearances in the newspapers, sensationalist pamphlets about his exploits were published and plays about him performed at cheap theatres. Three pamphlets were rushed out – claiming to be based on fact, but probably also including some fictional embellishments – in January and February 1838. A play of 1840 – Spring-heeled Jack, The Terror of London – depicted Jack as an outlaw driven to attack women because of a betrayal by his own sweetheart. In some Punch and Judy shows, the devil character was rechristened Spring-heeled Jack.

The Years Pass, But Spring-heeled Jack Keeps Appearing

Despite his rising fame, reports of encounters with Spring-heeled Jack began to dwindle. In 1843, however, there was a fresh surge of sightings across the country. Jack was spotted in Northamptonshire, where he was described as ‘the very image of the Devil himself, with horns and eyes of flame.’ In East Anglia, Spring-heeled Jack was held responsible for a series of assaults on the drivers of mail coaches.

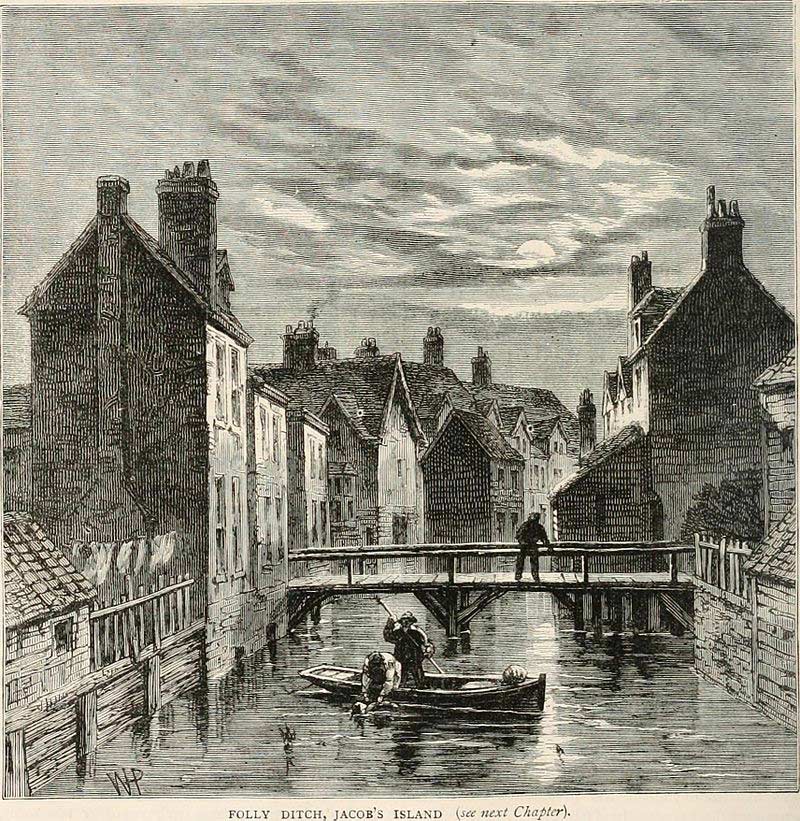

In 1845, Jack apparently bounded up to a prostitute – Maria Davis – on Jacob’s Island, a notorious South London slum located where the River Neckinger met the Thames. Jack is said to have grasped Maria in his claw-tipped hands and belched his trademark blue flames into her face. He then lifted her above his head before flinging her into one of the open sewers – called Folly Ditch – that ran through the neighbourhood. Maria struggled vainly before she sank beneath the foul waters.

In July 1847, Spring-heeled Jack was alleged to have committed a number of outrages in Teignmouth, Devon, ‘disguised in a skin coat, which had the appearance of a bullock’s hide, skullcap, horns and mask’. The ensuing investigation resulted in one Captain Finch being convicted on two counts of assaulting women. Some also blamed Spring-heeled Jack for the strange phenomenon of the ‘Devil’s Footprints’ – a 40-mile-long line of mysterious cloven hoof marks, mostly in single file, that appeared in the snow in Devon overnight in 1855. Whoever made the hoofprints seems to have been able to jump over rivers, haystacks and houses with ease.

Sightings of Spring-heeled Jack once more decreased until there was another panic in the 1870s. In 1872, the News of the World reported that Peckham was ‘in a state of commotion owing to what is known as the Peckham Ghost, a mysterious figure, quite alarming in appearance.’ This spectre, the paper claimed, was actually ‘Spring-heeled Jack, who terrified a past generation.’ The ghost was said to be tall and dressed in white. There were references to the phantom having a flaming face, the ability to leap fences and a fondness for wearing spring-heeled boots. In Sheffield, local residents began glimpsing a ‘Park Ghost’, who would also come to be identified with Spring-heeled Jack.

In one of his most infamous escapades, Jack was accused of harassing soldiers at the large military base in Aldershot, Surrey. At Aldershot’s North Camp one evening in March 1877, a sentry saw a strange figure emerge out of the darkness. The sentry shouted a challenge, but the figure strode straight up to him and slapped him several times across the face, with an icy corpse-like hand. Other soldiers fired at the intruder, but their bullets had no effect. The figure then vanished into the darkness ‘with astonishing bounds.’ More incidents occurred in April and the soldiers grew so unsettled that sentries were given live ammunition and told to shoot the ‘night terror’ on sight. But Jack would return to torment more sentries at the end of the summer. At Aldershot, Spring-heeled Jack is even said to have leapt the Basingstoke Canal – a channel 15 paces across.

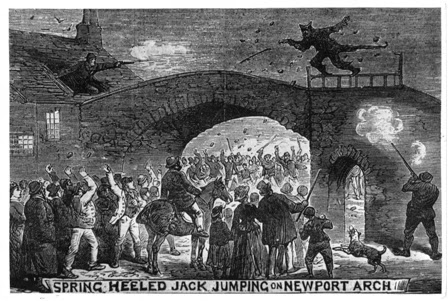

In the autumn of 1877, Spring-heeled Jack appeared in Lincoln, wearing the skin of a sheep. A mob chased him, but with his usual bounds and jumps, Jack escaped. Jack apparently leapt distances of 20 feet or more as he sprang across rooftops and he even bounded right over a Roman monument called Newport Arch. A few citizens shot at him, but Jack seemed impervious to their bullets.

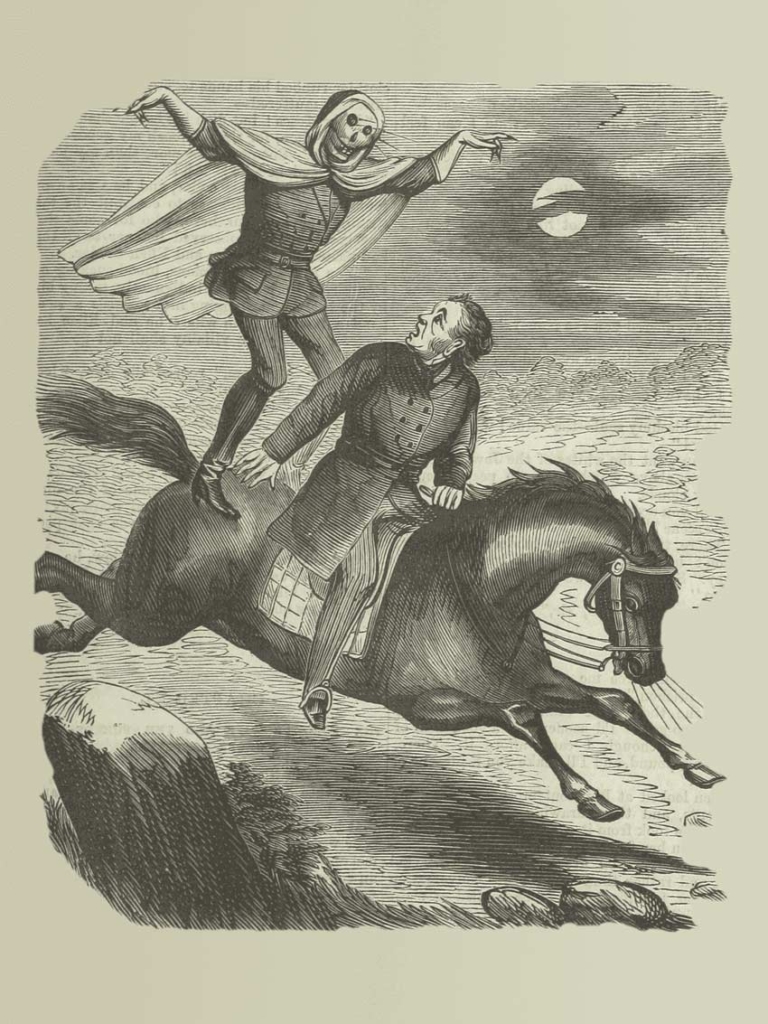

A somewhat sensationalist illustration of Spring-heeled Jack – in the guise of a bear – in Lincoln

In 1888, in the Everton district of Liverpool, Spring-heeled Jack was spotted on the roof of a church and – in 1904 – there were reports of him in the same city, in nearby William Henry Street. Here he is said to have taunted residents by bounding 25 feet up onto house roofs then jumping down into the street again. Locals described him as sporting a mask, long boots and a black cloak.

After the incident in William Henry Street, Jack seems to have faded into history and folklore, but I’ve found one reference to a hunt for Spring-heeled Jack in Glasgow as late as the 1930s. It’s not known if Jack was accused of committing any crimes against Glaswegians, but – interestingly – Glasgow seems to have been a frequent venue for ‘monster hunts’ in the 19th and 20th centuries. The city saw searches for hobgoblins, banshees, maniacs and even a being known as the Gorbals Vampire, who was said to haunt Glasgow’s Southern Necropolis.

So Who, or What, Might Spring-heeled Jack Have Been?

A number of explanations have been put forward to account for the strange phenomenon of Spring-heeled Jack. Read on for ideas about mad marquesses, phantom attackers, mass hysteria, ghosts, devils and notions about how Jack might have sprung, evaded bullets and breathed fire.

Could Spring-heeled Jack Have Been the Consequence of an Aristocratic Bet?

The Marquess of Waterford in 1840. Could he have been Spring-heeled Jack?

Even at the time of his first assaults, most people didn’t consider Spring-heeled Jack to be a supernatural being, but rather an individual – or individuals – in disguise who had a macabre sense of humour. Many – like the writer of the letter to the Lord Mayor – suspected Jack’s outrages were perpetrated by a group of noblemen as part of a wager. Popular rumour pointed to the young Irish aristocrat the Marquess of Waterford as the main culprit.

The Marquess was frequently in the news for his drunken brawling, violent practical jokes and participation in outlandish bets. The term ‘paint the town red’ comes from an episode involving the Marquess and his friends. After finding some red paint lying around in Melton Mowbray, they went on a drunken rampage, daubing houses and pubs while beating and painting red any police officers who tried to stop them.

There’s evidence the Marquess of Waterford might have been Spring-heeled Jack. The Marquess was famous for his disdain towards women. He already had a reputation for amusing himself by ‘springing on travellers unaware, to frighten them’ and he is known to have been in London around the time of the first Spring-heeled Jack assaults. The Marquess was noted as a sportsman, boxer and equestrian so – though no human could have performed Jack’s more outlandish feats – an athletic man like the Marquess may have been able to leap surprising distances and bound over gates. The boy in Turner Street, apparently, noticed a ‘W’ on Jack’s cloak as he fled.

As well as having the sadistic character and physical capabilities to undertake at least some of Spring-Heeled Jack’s crimes, the Marquess had the money and resources. In the days before mass public transport, few commoners would have had the cash or time to criss-cross London and its suburbs in the way Jack did, but this would have been less of a challenge for a nobleman in a coach. Wealth would also have been needed to procure items like suits of armour and bearskins. Many – including the authorities – felt a whole group of noblemen might be involved and there’s some evidence Jack didn’t act alone. Three men beat Jones the carpenter and Jane Alsop’s father suspected his daughter’s assailant may have had a helper.

The lull in Jack’s activities after 1839 could have resulted from the bet being fulfilled or those posing as Spring-heeled Jack becoming alarmed by the attention the press and police were focusing on the case. Imitators or spreading mass hysteria could then explain the later incidents.

The Marquess of Waterford may have carried out the earlier assaults – like those on Jane Alsop and Lucy Scales – but he couldn’t have been the perpetrator of Spring-heeled Jack’s later outrages. Around 1842, the Marquess seems to have reformed. He married and settled down in County Waterford, where he apparently led an exemplary life before dying in a riding accident in 1859.

Was Jack’s Legend the Product of Press Sensationalism and Mass Hysteria?

Even at the time of the early Spring-heeled Jack incidents, there was a certain amount of scepticism from the authorities and press. While many accepted that Jack’s escapades may have resulted from a sinister wager, some sightings of ‘Jack’ and some of the powers ascribed to him were suspected of being the product of an over-excited popular imagination.

Investigations by journalists showed that the glimpses of Jack in the form of ‘a large white bull’ were caused by nothing more uncanny than a white-faced heifer. Some of the accounts of ‘ghosts’ were shown to stem from the sight of a police officer in a white uniform on a horse. The reports of Jack scaling the walls of Kensington Palace to dance on its lawns were found to be inspired by an unrelated episode from 1822. As Jack’s fame expanded, it seems that a number of sexual assaults, crimes and acts of hooliganism – which, while distressing for their victims, weren’t exceptional in themselves – were added in the popular mind to Jack’s reign of terror. In addition, pranksters, criminals and sexual predators appear to have mimicked aspects of Jack’s legend to disorientate and terrify their victims.

Though some pressmen may have been sceptical about Jack, others were less so. The more outlandish accounts of Jack’s escapades in Lincoln, for example, come from The Illustrated Police News, a publication that reported crimes in a sensationalist and sometimes exaggerated manner.

There was also the influence of the numerous plays and penny dreadfuls churned out about Jack. These may have reminded people about Jack’s legend at times when it was fading from the collective memory. The play Spring-heel’d Jack or the Felon’s Wrongs was staged in 1863 while 1867 saw the release of the penny dreadful Spring-heel’d Jack, the Terror of London, A Romance of the Nineteenth Century. Another 40-part penny dreadful was published in 1863 and reprinted in 1867. Could these plays and publications have resurrected Jack in the popular mind and helped inspire the outbreak of sightings in the 1870s? More plays and pamphlets appeared between the mid-1880s and early 1900s. Could these have contributed to the reports of Jack’s final outrages around the turn of the century?

Spring-heeled Jack in the 1867 penny dreadful series ‘Spring-heeled Jack: The Terror of London’

Certain incidents weren’t even seen as the work of Spring-heeled Jack until declared so by the press. The case of the ‘Peckham Ghost’ of 1872 was extensively covered by two local papers, but they simply described this entity as a ‘ghost’ and made no mention of Spring-heeled Jack. The Peckham incidents were only linked to Jack – no doubt helping to reawaken memories of him – by the national papers The News of the World and The Illustrated Police News.

Later writers may also be guilty of exaggerating Jack’s legend. Mike Dash – in his excellent long essay Spring-heeled Jack: To Victorian Bugaboo from Suburban Ghost – suspects Peter Haining, the author of the 1977 book The Legend and Bizarre Crimes of Spring-heeled Jack, of embellishing or even making up a number of incidents. Dash has found absolutely no contemporary reports of the attack on Polly Adams on Blackheath and suspects Haining’s account of it may be an attempt to push his theory that the Marquess of Waterford was Spring-heeled Jack. Dash even suspects that the aristocratic ‘W’ seen on Jack’s cloak in Turner Street might be an invention of Haining’s.

Dash has also been unable to find any contemporary references to the murder of the prostitute Maria Davis, an incident that features prominently in Haining’s book. Dash suspects the Maria Davis story may have come from a woodcut showing two men in a boat apparently recovering a prostitute’s body from Folly Ditch. A closer examination rather suggests they are collecting drinking water.

Are these men pulling a body from Folly Ditch or just collecting water?

Alarming – though not particularly uncanny episodes – have sometimes been incorporated into the Spring-heeled Jack myth. The stories of Jack’s activities in Liverpool in 1904 seem to have their source in the behaviour of a mentally ill man. 60 years after the events, a Mrs Pierpont, who had lived in the neighbourhood all her life, said ‘Jack’ was a local man who ‘was slightly off-balance mentally …. He had a form of religious mania and he would climb on to the rooftops of houses crying out: “My wife is the Devil!”’

‘They usually fetched police or a fire-engine ladder to get him down. As the police closed in on him, he would leap from one house roof to the next. That’s what gave rise to the Spring-heeled Jack rumours.’

It does seem, however, that some of the Spring-heeled Jack incidents really did occur and really were something out-of-the-ordinary, especially the assaults on Jane Alsop and Lucy Scales. But even here, there seem to be some discrepancies about what Jack actually did. Jane and her sisters, for instance, insisted that Jack had breathed fire while two eye-witnesses – men called Richardson and Smith – maintained that Jack didn’t belch any flames.

Smith said, ‘I saw no light but that of a candle’ and Richardson reportedly stated that the assault on Jane didn’t ‘impress him with the idea that it had been so furious as he subsequently saw it described in the newspapers.’

What Could Explain Jack’s Leaps, Fiery Breath and Other Startling Characteristics?

Some of Jack’s outlandish attributes – his ability to make massive leaps, his fire-breathing, his metal claws, his apparent imperviousness to bullets – seem so impressive that people have wondered whether he was in some way supernatural or not of this world. Later writers have speculated that Spring-heeled Jack might have been an alien – perhaps from a planet with stronger gravity than our own – or that he could have been a demon summoned, deliberately or accidently, by occultists.

During the Victorian era, Jack was mostly seen as human though the frequent references to him as a ‘ghost’ or ‘devil’ do suggest some suspected his powers might have uncanny origins. But could there be any rational explanations for the astounding abilities Jack was credited with?

Spring-heeled Jack’s Fiery Breath

One of Spring-heeled Jack’s most alarming features was his fire-breathing. Only four incidents, however, are said to have involved Jack belching flames – the Polly Adams and Maria Davis attacks (which might not have occurred) and the assaults on Jane Alsop and Lucy Scales. As we’ve seen, there’s some debate about whether the Alsop assault involved fire, but – assuming Jack did breathe fire during the attacks on Jane and Lucy – how could he have managed it?

It’s likely Jack used a fire-breathing trick of the kind performed in circuses and at carnivals, by filling his mouth with a flammable fluid and spurting it onto a flame. This could explain the blue-and-white colour of Jack’s fire. In the attacks on Jane and Lucy, Jack needed a flame to pull off his trick – he asked Jane for a candle and he was holding a lamp when he assaulted Lucy. In both attacks, he is said to have held the light at the level of his chest, which is what fire-breathers do. The police at the time suspected Jack was using some sort of carnival technique and they talked to circus fire-breathers to try to work out how he could have done it.

This sort of stunt would be very dangerous. Because the slightest breeze can result in the flame igniting the liquid while still in the fire-breather’s mouth, the trick is usually only performed indoors. The evenings when Jack attacked Jane and Lucy seem to have been calm, but perhaps the hazards of such a prank meant Jack wasn’t keen to undertake it more than twice. After the attacks on Lucy and Jane, he may have decided to lay aside the flame-spurting part of his repertoire or given up his attacks altogether, to be replaced by lesser imitators incapable of fire-breathing. Jack’s costume of a helmet and white oil-skin may have been designed to lessen his risk of injury if an accident did occur.

It’s unlikely that Jack breathed fire straight into his victims’ faces. This would have resulted in horrendous injuries, but there’s no record of Jane or Lucy receiving burns and Lucy is said to have only been blinded temporarily. If Jack did breathe fire, the reports of him vomiting flames directly into faces are probably exaggerations.

Spring-heeled Jack’s Leaping Abilities

What could explain Spring-heeled Jack’s incredible leaps?

If attempted by humans, Jack’s most spectacular leaps – jumping over high walls and down from roofs – would have led to smashed ankle bones.

In the earlier accounts of Spring-heeled Jack, his leaps – while impressive – are often less incredible than those of his later career. Sometimes, he didn’t leap at all. Following the attack on Lucy, Jack just strode off; after the assault on Jane, he merely ‘scampered away across the fields.’ But Jack’s leaping abilities were soon emphasised. This could have been the result of exaggerations among the public – as in the 1904 Liverpool case – or in the press, as in the Illustrated Police News account of Jack in Lincoln. Some of his most spectacular jumping feats don’t appear until they’re featured in accounts written years after the incidents they proport to describe. There are no contemporary records of Jack leaping the Basingstoke Canal – such a claim doesn’t appear until 1907, three decades after the events at Aldershot.

An interesting account of Spring-heeled Jack was given by a lady who claimed to have seen him fleeing across Tooting Bec Common. The lady observed Jack ‘jumping over good-sized furze bushes and clumps of grass with no apparent effort, though she came to the conclusion that any greater leap would have been impossible. He was doing far more than any ordinary man could have accomplished without mechanical aid, but nothing resembling the exploits with which he had been credited by rumour. Had a good horse been near, he could have been overtaken, but as it was, he escaped, the mist and gathering night helping him.’

Might Jack have been a vigorous and athletic young man, whose leaping feats, though astonishing, didn’t become superhuman until they were exaggerated?

It’s also unlikely that Jack wore spring-heeled boots. Such boots would only be of use on firm, fairly even ground and many of Jack’s exploits took place on the rougher terrain of parkland, heaths, fields, county lanes and badly paved city alleys. In addition, springs wouldn’t have been powerful enough propel Jack over high walls and houses.

Jack’s Talons and Imperviousness to Bullets

Spring-heeled Jack’s metal talons are easy to explain – they could have been fitted to specially designed gloves. What’s more puzzling is Jack’s apparent ability to deflect bullets.

In Lincoln, (assuming Jack was fired at and such accounts aren’t exaggerations) the locals’ pot shots may have missed or been deflected by Jack’s sheepskin. But in the Aldershot case, it seems stranger that Jack could have dodged the bullets of trained soldiers.

When Jack first appeared at the base, the shots fired at him were blanks. Jack was fired on with real bullets when he turned up again in April 1877, but escaped harm thanks to poor shooting on the part of startled sentries.

The Times reported, ‘A soldier, in his excitement, loaded his rifle, fired but missed his aim. From here, the ghost went towards the military cemetery and in a similar manner attempted to frighten a private … and was fired at again, but without being hit.’

By the time Jack returned at the end of summer, the guards were no longer using live ammunition. According to the Illustrated Police News, sentries had ‘been ordered to fire on the ghost, and were loaded with ball, but this precaution being lately given up, Jack pursued his old tactics on Friday last …’

This suggests Jack was aware of the order to use live rounds and also knew when that order was rescinded. This leads one to suspect Jack had inside knowledge of the workings of the camp and was probably a soldier stationed at Aldershot.

It’s likely the Aldershot Jack was a young, athletic army officer fond of playing pranks on his fellow soldiers. Some serving at Aldershot had their suspicions about Jack’s identity.

A retired colonel, looking back 30 years later, said, ‘The pranks were popularly attributed to a lively young officer of the Rifles … a very big, powerful man, extraordinarily active … he certainly was not convicted of them and I do not know that he ever acknowledged himself to be Spring-heeled Jack.’

Spring-heeled Jack’s Legend Could Be Built on Strong Urban Traditions of Ghosts, Devils and Phantom Attackers

The tales of Spring-heeled Jack could have been influenced by earlier urban legends of ghosts, devils and bogeys. Jack’s outrages likely reawakened such terrors in the collective mind. These terrors then became linked to Jack’s myth, strengthening it further.

London has a long folklore of ghosts haunting its streets – pale, human-like entities that assault lone travellers. In 1803-4 and again in 1824, a being known as the Hammersmith Ghost was said to rove the city’s western fringes. This spectre – suspected to be the spirit of a local suicide – was accused of attacking pedestrians. The ghost had similarities to Spring-heeled Jack. He was described as being very tall and dressed in white clothes, over which he wore a long dark coat with shiny buttons. Other descriptions have the ghost sporting a cow-skin, horns and large glass eyes. Like Jack, the Hammersmith Ghost was good at outrunning and evading pursuers and several of his victims were said to have died of shock. Another famous urban spectre was the Southampton Ghost. This phantom was said to be 10 feet (3 metres) tall and – like Spring-heeled Jack – fond of jumping over houses. Jack’s ‘ghostly’ aspects can also be seen in the fact he never seemed to age. He was just as athletic and vigorous in the 1870s as when he first emerged in 1837.

Spring-heeled Jack in the guise of a ghost

Another ‘ghostly’ or ‘devilish’ aspect of Jack was his ability to manifest in different forms. In addition to his spring-heeled persona, he could appear as a white-sheeted ghost, a bull, a bear, a devil or ‘an unearthly warrior clad in armour of polished brass’. Sometimes Jack even mixed his personas – for example, appearing as an armoured man draped in a bearskin and sporting horns.

This drew on an old tradition that evil spirits often disguised their identities, including by masquerading as animals. So it would have seemed less puzzling to the Victorians than to us that Jack could assume different forms while remaining the same entity. Jack’s flaming breath and occasional cloven hooves also drew on traditional representations of devils and demons. The animal hides Jack sometimes sported reflect ancient associations between animal skins and fertility, especially the skins of bulls. Such associations emphasised Jack’s sexually predatory characteristics. Jack’s sexually aggressive imitator Captain Finch wore a bull’s hide.

Spring-heeled Jack’s devil-like aspect is depicted by the sensationalist ‘Illustrated Police News’.

Spring-heeled Jack also fits into the tradition of ‘phantom attackers’: criminals that – though human – are so sadistic and strange they have an aura of the uncanny or demonic. One of Jack’s predecessors was the London Monster, a man reported to have stabbed over 50 women between 1788 and 1790. Some accounts of the Monster claimed he had knives attached to his knees, others that he hid blades in bunches of flowers, which he then encouraged women to smell.

Another assault by a ‘phantom attacker’ is said to have occurred in 1826. A young man walking down Commercial Road at midnight was attacked by a cloaked and masked individual with cloven hooves for feet. The attacker grasped the man and squeezed him against his body, which seemed to be on fire. During his desperate struggles, the badly burned victim pulled the mask away to find his assailant was his younger brother.

Many of Jack’s characteristics seem to stem from universally held architypes of springing, devil-like, sometimes fire-breathing characters who leap out of the darkness to attack or terrify their victims. Accounts of Spring-heeled-Jack-like creatures can be found in various parts of the world. In 1926, a ‘ghost’ plagued Bradford’s Grafton Street. The ghost – described as tall, athletic, ‘glowing’ and ‘on springs’ – escaped his pursuers by bounding over rooftops.

In 1951, a tall, thin, cloaked spectre haunted a housing project in Baltimore. This highly athletic entity was fond of leaping onto rooftops and scaling high walls. A being known as the ‘Black Flash’ or ‘Phantom’ menaced Provincetown, Cape Cod, from 1938 to 1944. Black Flash was said to jump incredible distances and spit blue flames. He had eyes like balls of fire and some suspected he wore springs on his feet.

During the Second World War, a ‘Spring Man’ was rumoured to roam the blacked-out streets of Prague, leaping at passers-by from alleyways. In the 1950s, white-clad, hopping, mannequin-like creatures caused a panic in East Germany. In 2001, mass hysteria was sparked by a ‘Monkey Man’, who apparently attacked people in Delhi at night. Victims described the Monkey Man as having glowing red eyes and metal claws. He was said to wear a helmet and tight-fitting clothes and to be capable of leaping four storeys.

So What’s the Conclusion? What Could Account for the Strange Phenomenon of Spring-heeled Jack?

I suspect there was a ‘real’ Spring-heeled Jack – active around 1837 and 1838 – and that this Jack was definitely human. The original Jack was probably responsible for the assaults on Jane Alsop and Lucy Scales and for some of the other outrages that occurred around that time. It’s likely Jack and his cronies were young rich men – possibly engaged in a bizarre wager – and that Jack was exceptionally athletic. Jack may have also been capable of fire-breathing tricks.

The sheer strangeness of Jack’s assaults caused an upsurge of mass hysteria, rumours, exaggerations and press sensationalism. Pranksters aped some of Jack’s actions while crimes carried out by ordinary criminals and sex offenders were blamed on Spring-heeled Jack, further fuelling his notoriety. Penny dreadfuls and lurid plays amplified Jack’s fame as did embellishments by authors writing years after the events.

Jack’s antics dredged up archetypes of devils, ghosts and sadists from the collective memory, adding even more sinister colour to his legend. At times of panic, trauma or uncertainty, such archetypes can indeed coalesce around certain folkloric figures, figures that soon take on aspects of the myth-drenched past. Examples of such beings that have – like Jack – incongruously appeared in relatively modern epochs include the Highgate Vampire, the Manchester Mummy and the Cardiff Giant.

But perhaps Spring-heeled Jack – as an updated ‘devil’ or ‘phantom’ – was also a personification of the injustices and cruelties of the Victorian era, representing the tendencies of the rich and powerful to prey on lower social classes and men to prey on women. In addition, Jack – with his iron claws, metal springs and chemical breath – could be seen as a spectre of the emerging machine age, personifying the dangers of urban life in a rapidly industrialising country.

Though Jack’s fame has faded somewhat, he has featured over the years in comics, novels, TV programmes, video games and films. In parts of Britain, he has lingered on as a bogeyman figure, threatening to spring in through the windows of children who refuse to go to bed. One Exeter man recalled:

‘My maternal grandmother, who died at an advanced age, was accustomed to tell me, when I was a little lad, uncanny stories about Spring-heeled Jack, who, she asserted, was the Marquess of Waterford. The monster was credited with hiding at night in dark and lonely places and, when some chance pedestrian came along (by preference a solitary female), Spring-heeled Jack would suddenly leap out at one bound, and pin his unlucky victim to the ground.’

(This article’s main image is courtesy of Fortean Slip, from YouTube)

The William Henry street also had a ghost or poltergiest according to repoerts which may have also fed into the SHJ as large mobs gathered to see the ghost in an empty house !